To support the launch of Out in Tech’s Miami chapter.

Program Area: Community Impact

To support the engagement and programming of Floatlab, a new floating dock and classroom at Bartram’s Garden.

Knight Foundation asked four leading scholars and community leaders to consider this question: “What is the most important trend that will transform how Americans think about community over the next decade?” Ali Noorani, Executive Director, the National Immigration Forum, shares insights below. Click here to download and view all essays.

Unprecedented global migration, how it is perceived and how it is experienced, is the prism through which we will understand the 21st century American community. How we respond determines what kind of America future generations live in.

In just over 25 years the number of international migrants in the world increased approximately 70 percent to reach 257.7 million. In the same period, the U.S. foreign-born population more than doubled to reach 49.8 million immigrants in 2017. Along the way, America experienced the Great Recession and economic disruptions driven by technology and globalization that changed the way we work and the way we relate to one another.

Over the course of 2018, the National Immigration Forum convened 26 Living Room Conversations to better understand how Americans are grappling with these changes. What we heard, what we learned, offers a roadmap for civic leaders across the political spectrum to help communities grapple with the politics of immigration.

Over the last few years, stories of mass migration have found their way to our homes, filtered through our news feed of choice, bringing a level of urgency to the debate. For many of us, when we see the Central American child on the train or the Syrian family in the raft, we are led to believe by certain press and politicians that they will be our neighbor in a matter of weeks. As our communities diversify, through marriage or migration, our new neighbor reminds us of what we saw on our screen. Diversity brings to our communities new languages, new customs, new religions. Our divisive politics define our perception, creating unease and insularity.

The fragmentation of traditional media and the powerful influence of social media bring these changes into sharp focus. We don’t trust our institutions, so we turn to our friends and family for the information and influence that shapes our opinion. For Americans worried that their children will not be better off than they are, it feels like the movement of goods, people, commerce, and ideas presents future generations an overwhelming set of economic and social challenges.

In some cases, leaders respond with a hardened politics, the building of actual and metaphorical walls, legislation that seeks to exert greater control at the local and national level. Paralyzed by anger and fear, the politics and policies of these communities stymie growth. And that feeds into the sense of victimhood as neighboring communities that embrace the challenges and opportunities of immigration see greater economic growth.

The combination of a more diverse America and a rapidly-changing economy has exacerbated a perception that immigrants and immigration are a threat, not a benefit, to American communities.

Those policy makers looking to lead more inclusive communities, buoyed by the rule of law, thrive with growing, diverse populations. They do the hard work necessary to help communities understand the changes around and beyond them. Fears are acknowledged and addressed, not dismissed and ignored. Programs and policies are put into place to welcome immigrants and refugees into the community without displacing native born residents.

The combination of a more diverse America and a rapidly-changing economy has exacerbated a perception that immigrants and immigration are a threat, not a benefit, to American communities. In this new normal, there are two paths we can take. One leads to an expanded sense of community, positively influenced by a diversity of sights, sounds and relationships that come from global migration. The second, darker path is more insular, narrowed by fears of immigration.

These days, it feels like America has chosen the second path where leaders are quick to sow seeds of xenophobia and division. The seeds that lead to cultural, security and economic fears define the questions that polarize the nation’s immigration debate:

- Culture: Are immigrants and refugees isolating or integrating? Do they live in isolated enclaves, or are they immersed in the community, learning English and becoming American?

- Security: Are immigrants and refugees threats or protectors? Are they national security or public safety threats, or do they make positive contributions to communities, even serving in law enforcement and in the military?

- Economy: Are immigrants and refugees takers or givers? Are they taking jobs and benefits, or are they economic contributors?

Rather than help Americans understand and facilitate the cultural and economic changes around them, supporters of immigration ignore these questions, while anti-immigrant forces weaponize them. Yet, we observed that when Living Room Conversations participants were able to voice their fears and feel heard, the discussion migrated away from division towards solutions.

Changing course requires us to understand the broader context of demographic change, the fears Americans have, and, more importantly, how to acknowledge and address those fears. Only then can America live up to the ideal of e pluribus, unum – “out of many, one.”

A Changing Nation

In a historical context, what we’re experiencing is not new. In 1890 and again in 1910, U.S foreign-born residents and citizens made up at least 14.7 percent of the nation’s population. Decades of xenophobia and political backlash followed the 1910 crest, resulting in multiple laws restricting immigration. Today, with 13.7 percent of the United States’ current population being foreign born, we are at a similar inflection point . What lies ahead depends on how Americans think about and engage with community.

Today, more than 40 million U.S. residents and citizens were born in another country. And, while immigration of generations past diversified the ethnic makeup of the nation, modern day immigration has made today’s America more racially and ethnically diverse than ever before. The Pew Research Center paints a colorful statistical portrait of America in 2016 where Mexican immigrants accounted for 26 percent of the nation’s foreign born, with the next largest origin groups are those from China (6 percent), India (6 percent), and the Philippines (4 percent). And America will only become more diverse in the years ahead, with Asians as a whole projected to become the largest immigrant group by 2055.

The diversification of America’s communities is not wholly dependent on future immigration. In fact, new U.S. Census estimates found that for the first time, in 2013 over half of babies born in the U.S. were non-white. Which means, “non-Hispanic whites will cease to be the majority group by 2044.

The challenge is that the combination of demographic and economic changes is hard to unpack for Americans who see their community and their livelihood changing at the same time.

For recent generations of Americans, a diverse America is the reality they were born into. But, for the nation’s Baby Boomers — those born between 1946 and 1964 — these were tectonic shifts that rattled their economic and social framework. In 1960, 88.6 percent of the U.S. population was white, dropping to 72.4 percent in 2010. In 1970, 4.5 percent of the nation’s population was Hispanic. Just 40 years later the Hispanic population quadrupled to 16.3 percent.

The challenge is that the combination of demographic and economic changes is hard to unpack for Americans who see their community and their livelihood changing at the same time.

In the 1990’s, as the nation’s immigrant population began to grow, the Baby Boomer generation peaked at 78.8 million. At this point, Baby Boomers were between 25 and 45 years old, and beginning to start their families, worrying about college tuition and job prospects for their children. And along comes immigration and globalization to fundamentally reshape their socioeconomic reality.

As American Action Forum President Douglas Holtz-Eakin said in 2016 before the House Ways and Means Committee, from World War II to 2007, the economy grew fast enough that GDP per capita — a crude measure of the standard of living — doubled on average every 35 years, or one working career. Coming out of 2008’s Great Recession, projections indicated that it would double every 75 years. And, in 2016, those households that worked full-time for the full year saw zero increase in their real incomes. As Holtz-Eakin put it, “The American Dream is disappearing over the horizon.” For many Americans experiencing this new reality, particularly as their children came of working age, immigration was a source of competition, not of optimism.

It isn’t hard to see why Americans are feeling stress and anxiety about their future. Demographic, economic and cultural shifts lead them to question their sense of community and turn too quickly to blame immigrants as the source of their problems. Our politics track this anxiety as the generational and geographic divide between political parties grows. So much so that the difference in generational diversity is driving not only a competing sense of community, but divergent political priorities.

Our starting point in this case is the fact that nearly half of Americans under the age of 20 are minority, while over three-quarters of those 65 and older are non-Hispanic white. William Frey, a Brookings Institution demographer, writes, “The rapid growth of minorities from the ‘bottom up’ of the age structure is creating a racial generation gap between the old and young that reflects the nation’s changing demography.” He finds that 75 percent of the population over age 55 is white, while 54 percent of those under age 35 are white – a “gap” of 21 percent, nationally. As a result, the lived experience of Baby Boomers is fundamentally different than Millennials; a difference that lays the foundation for very different perspectives on community.

Most importantly, Frey finds, “The gap is especially high in states that that have received recent waves of new minority residents to counter more established old whiter populations: Arizona leads all states with a gap of 33 percent.” Nevada, New Mexico, Florida and California round out the top five. With the exception of New Mexico, all five states have been the epicenter of heated immigration debates as older voters pressure lawmakers to clamp down on immigration through a range of local enforcement policies.

To state the obvious, our changing nation has changed our politics. The echo chamber nature of our political debate creates bubbles where perceptions of community are narrow and divisive. Driven by primary elections, policy makers have little incentive to explain these changes to their electorate, much less reach out beyond their base. As a result, a racial and geographic divide to our politics settles in.

Luzerne County, which includes and surrounds Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, provides a 2016 election example. The county’s diversity index — which measures the variance of the racial and origin-based composition of a given population — increased by 360 percent from 2000 to 2015. It was one of the counties that saw a dramatic swing from blue to red in 2016. President Barack Obama carried Luzerne County by nearly 5 percentage points in 2012. Four years later, based on a campaign defined by racial and geographic fearmongering, President Trump carried the county by more than 19 points.

The racial gap between the parties grew in 2018. While 54 percent of whites voted for Republicans, African Americans, Latinos and Asians voted for Democrats at 90 percent, 64 percent and 69 percent, respectively. And, geographically speaking, urban and suburban voters preferred Democratic candidates, while voters in small towns and rural places favored Republicans.

Estimates indicate that by 2040, approximately 70 percent of Americans will live in the 15 largest states. Even as New York City, Los Angeles and Houston continue to see population growth, 30 percent of the country’s population — living in smaller states without major metropolitan centers — will hold disproportionate electoral power. Unless political and civic leaders have strategies to help communities understanding the changes they see (or read about), political dysfunction will lead to national tension.

Coming of age in big cities that include a greater range of economic opportunities, many (mostly liberal) Americans are insulated from the demographic and cultural changes Americans in suburban or rural communities struggle with. Diverse, urban environments have been built over generations, and the changes there have been steady and gradual. While not perfect or easy, cities allow youth and families to familiarize themselves with the idea of diversity. Over time, it becomes the norm as institutions in urban areas shape, and were shaped by, the diversity of the populations they served or engaged.

Suburban and rural parts of the country, home to an older and white population, with less access to the spoils of the technology economy, experienced these demographic changes more recently, and more dramatically. The changes that took place were proportionately larger, faster, and more acute – and accompanied changes as the global economy shifted. Demographic changes became a proxy for economic disruption.

Unless we change course, the political divide between young and old, rural and urban, will only widen as migration pressures are exacerbated by continuing economic shifts. Needless to say, the need for a different understanding of the American community has a certain level of urgency.

With or without immigration, the American community is becoming more diverse. As Richard Longworth of the Chicago Council for Global Affairs put it, “You can’t build a wall against hormones.” Which means we are not going to return to the Baby Boomer definition of America.

So charting a viable path toward compromise and common purpose requires us to meet people where they are, understanding the origins of their hopes and fears and reactions to their fast-changing communities. Our current politics and politicians limit the opportunities to do this kind of work. Ultimately, we must work together to hold elected officials from both parties accountable for divisive rhetoric.

Understanding the Fears

Deepened understanding of these fears and anxieties starts with careful listening. The National Immigration Forum works to engage conservative and moderate faith, law enforcement and business leaders living in the Southeast, South Central, Midwest and Mountain West, regions that have experienced some of the fastest growth in the foreign-born population and are struggling with the political and cultural changes that come with it.

In the sprint of 2018, Forum staff traveled to dozens of rural and suburban communities in conservative regions of the country to convene “Living Room Conversations.” We tapped into our networks of faith, law enforcement and business leaders to recruit 10-15 participants per conversation in order to better understand how conservative leaning rural and suburban communities perceived a changing America. A discussion guide designed by a team of researchers helped us lead robust and open conversations that included themes of identity, community and polarization, and perceptions about immigrants.

We launched this learning campaign to test our hypothesis that Americans grapple with three specific fears that lead to critical questions of our changing sense of community:

- Culture: Are immigrants and refugees isolating or integrating? Do they live in isolated enclaves, or are they immersed in the community, learning English and becoming American?

- Security: Are immigrants and refugees threats or protectors? Are they national security or public safety threats, or do they make positive contributions to communities, even serving in law enforcement and in the military?

- Economy: Are immigrants and refugees takers or givers? Are they taking jobs and benefits, or are they economic contributors?

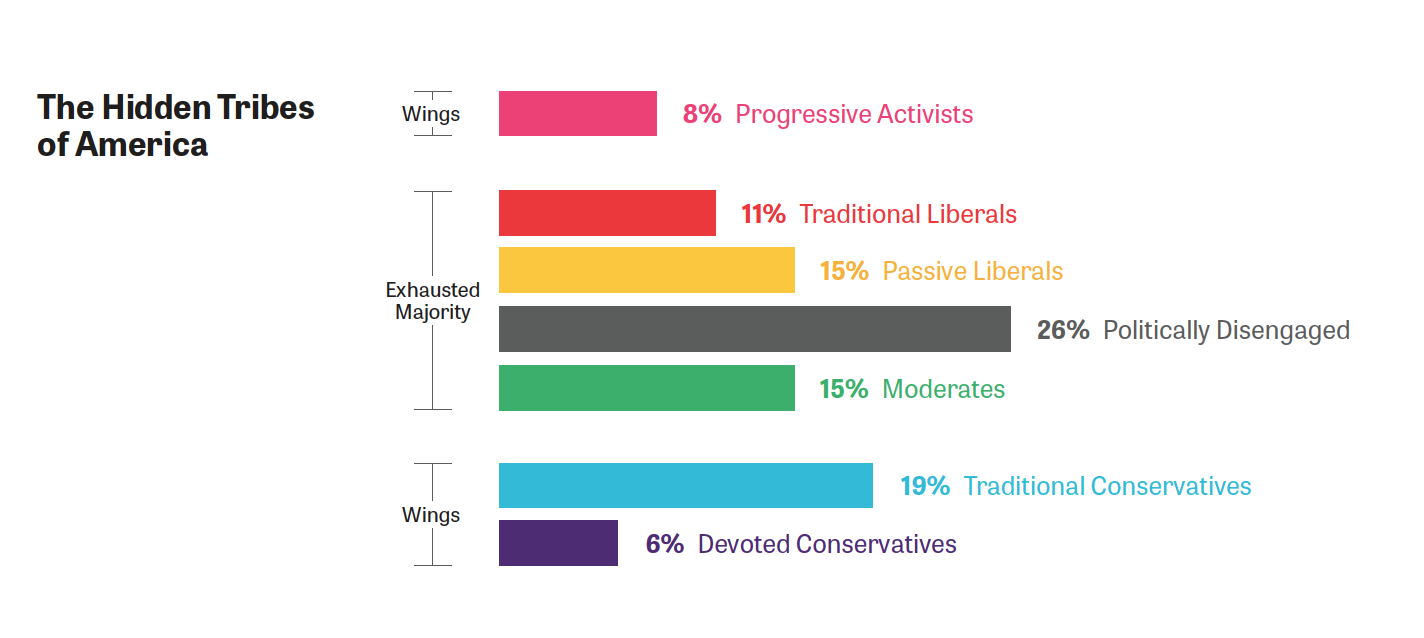

To complement our findings, we partnered with More in Common, an international initiative to build stronger and more resilient communities and societies, which had just completed an exhaustive quantitative survey of the American public. More in Common’s report, “Hidden Tribes: A Study of America’s Polarized Landscape,” provides greater texture to these issues. Rather than a typical conservative versus liberal categorization of the public, their research led to a segmentation of the American public into seven tribes. Four of the tribes, they concluded, are a part of the “Exhausted Majority.”

More in Common’s findings aligned with the results of our Living Room Conversations, “Unsettling changes in our economy and society have left many Americans feeling like strangers in their own land.” They defined the Exhausted Majority as being:

- Fed up with the polarization plaguing American government and society

- Feeling forgotten in the public discourse, overlooked because their voices are seldom heard

- Flexible in their views, willing to endorse different policies according to the precise situation rather than sticking ideologically to a single set of beliefs

- Believe we can find common ground

Just because the Exhausted Majority is, well, exhausted, it doesn’t mean they agree on the issues. Their views on issues range across the spectrum but they are turned off by polarization, feel disregarded in the public discourse, and are flexible in their views. So, while there are certainly a large number of Americans trying to find consensus on our nation’s changing communities, finding that consensus requires careful listening.

As the authors wrote, “It would be a mistake to think of the Exhausted Majority merely as a group of political centrists, at least in the way that term is traditionally understood. They do not simply represent a midpoint between the warring tribes of the left and right. They are frustrated with the status quo and the conduct of American politics and public debate.”

This mirrors what we saw in our 26 Living Room Conversations across the country in 2018. Participants wanted leaders to hear their concerns. They sought information they can trust. And there was an unambiguous desire to rise above polarization and divisiveness in order to build coalitions and advance overdue policy reforms.

Before specific fears or anxieties came to the fore, questions of identity undergirded the conversation.

Francis Fukuyama wrote that the nation’s identity crisis is exacerbated by the perception of invisibility. “The resentful citizens fearing the loss of their middle-class status point an accusatory finger upward to the elite, who they believe do not see them, but also downward to the poor, who they feel are unfairly favored.” Therefore, “Economic distress is often perceived by individuals more as a loss of identity than as a loss of resources.

The perception that one’s job is going to be taken by the Mexican next door, or the Mexican in Mexico, creates a deep distrust of demographic change and the elites who seem so comfortable with it. Again, perception melds into reality and our political leaders are ill equipped to navigate the changes – or, more often, exploit the changes to divide rather than unite the electorate.

Fukuyama goes on, “The rightward drift also reflects the failure of contemporary left-leaning parties to speak to people whose relative status has fallen as a result of globalization and technological change.” The nation’s changes are much bigger than demography.

The authors of a new book, Identity Crisis, define “racialized economics” as “the belief that undeserving groups are getting ahead while your group is left behind.” As Washington Post columnist Dan Balz explained, “Issues of identity — race, religion, gender and ethnicity — and not economics were the driving forces that determined how people voted, particularly white voters.” We know from recent data that 69 percent of Americans — including 56 percent of Republicans — believe immigrants are “an important part of American identity.” But what shines through in our work, whether it was the Living Room Conversations or our broader approach, is that the when you localize the concept of “identity,” the term speaks as much to people’s hopes as to their fears.

“You’re a little bit of everything, and that’s really what America is … and that is the beauty and some of the angst in America … that you don’t want to give up your heritage.”

In Corpus Christi, Texas, we heard about the loss of American identity, while in Memphis, Tennessee, we heard that the church can be a powerful entity that organizes efforts to build transformative and inclusive national identities. In Gainesville, Florida, a man told us that “we are tribal and can’t handle difference,” whereas up the road in Tallahassee, we heard, “One of America’s proudest and most beautiful things is that it is a melting pot of cultures.” In Bentonville, Arkansas, a participant remarked, “You’re a little bit of everything, and that’s really what America is … and that is the beauty and some of the angst in America … that you don’t want to give up your heritage.”

Identity also speaks to a person’s community; which, at times, is different from the idea of an American identity. Numerous participants told us their identities were tied to their local communities, their neighborhoods, their sense of place. In Texas, unsurprisingly, there was a strong affinity with the idea of being “a Texan.” And Bentonville had a deep sense of civic pride when participants talked about the community’s growing diversity. Overlooking people’s economic concerns would be an error, but so would underestimating the power of identity as it underlies broader fears and anxieties people have.

With change taking hold all around them, we watched law enforcement officers, small business owners, and pastors — in real time — soul-searching, exploring what these changes mean to their own identities. Those who were hopeful saw their identities connected to larger themes of values and ideals. Those who were fearful found themselves in the midst of “an identity crisis.” But if they felt heard, if their opinion mattered, the tension melted out of the room.

So, why does the imperative to help America reimagine a sense of community in this global environment feel so challenging?

We need to move past binary arguments that attempt to delineate between race and class concerns. As our work has demonstrated, Americans experience immigration in a much more complicated way; our explanation of immigration, and engagement of the public, has to be just as complex.

Culture: Are immigrants integrating or isolating?

While cultural concerns are linked to identity, participants spoke to them in the context of a changing country, not always how they identified within those changes. For some participants, issues of race and ethnicity were central. For others, language determined whether an immigrant was integrating into American culture. Diversity and inclusion were also a consistent theme; as one participant in Fresno, California, said, “We don’t celebrate diversity … and too often it’s been us and them.”

A participant in El Paso, Texas, captured the tension between cultural integration: “It’s just easy to be American, and that is what this country is about, that we assimilate and unite as Americans … and I see that as a problem with some immigrants that want to isolate themselves and try to continue their own cultural behaviors — styles and behaviors … while they want to take advantage of the privileges of America … ”

In Appleton, Wisconsin, we heard that immigration “grows our culture, makes us more educated, [and] better people.” In Lubbock, Texas, a participant remarked, “I think [immigrants] bring a lot to our community by way of service and family values.” But in Las Vegas, Nevada, we heard that although immigrants are viewed as patriotic and hardworking, there were anxieties around a loss of cultural and language unity.

The conversations echoed More in Common’s findings: that freedom, equality and the American Dream are beliefs that make someone American, and that the ability to speak English can be valued as an important marker of American identity.

Security: Are immigrants threats or protectors?

Since the Sept. 11 attacks, security and terrorism concerns have loomed large in the nation’s immigration debate. More recently, the administration’s enforcement actions at the border and in the interior, along with progressive efforts to “Abolish ICE” and create “sanctuary cities,” have further polarized the debate. As the Trump administration falsely conflates immigration, terrorism and crime in order to achieve political goals, voters are left looking for information they can trust.

Our conversations indicated that personal relationships mitigated fears that center on security. People were willing to extend the benefit of the doubt to the “good” immigrants they knew. But many participants indicated that portrayals of immigrants as security threats are pervasive throughout the media. Therefore, even if people believe that such portrayals are misleading, what they read in the newspaper or saw on the television influenced their opinions.

Some 65 percent of Americans, including 42 percent of Republicans, do not believe that undocumented immigrants are more likely to commit serious crimes, according to Pew Research. This maps to reports that show, “immigrants are much less likely to commit crimes than the native-born.”

In the border town of El Paso, we observed a tension between some Americans wrestling with a desire to be compassionate as they fear threats posed by unauthorized immigration. The conversation in Mesa, Arizona, which included a handful of local law enforcement officers, revealed that although issues of legality and criminality continue to plague local residents’ perceptions and attitudes, participants generally agreed that immigrants do not pose an increased security threat. In Parker, Colorado, the sense among participants was that the broader community did believe immigrants posed a security threat.

Security fears are difficult to overcome. Even if someone feels immigrants are not a threat, one tragic incident, one hyperbolic headline, can plant a seed of doubt. All of which underscores the importance of local law enforcement in the conversation about the changing American community.

ECONOMY

We often hear that immigrants have a bootstraps mentality — they work as hard as they can to build a better life. Data suggest that these participants are echoing national sentiment. A 2017 Gallup Poll found that 45 percent of Americans believe immigrants make the economy better overall, compared with 30 percent who believe immigrants make the economy worse overall. It’s a sentiment that lines up with the contributions immigrants make to the U.S. economy: According to New American Economy, immigrants paid $105 billion in state and local taxes, and around $224 billion in federal taxes, in 2014.

Participants in southern border communities, where the economy is closely tied to Mexico and to immigration, recognized the economic benefit of immigration. In San Marcos, California, participants saw that the economy is dependent on the ability of businesses to buy and sell in both the U.S. and Mexico. There was general agreement among participants in Corpus Christi that immigrants were an economic benefit. On the other hand, thousands of miles from the border in Spartanburg, South Carolina, participants remarked that some in the community invoked the economy as a reason to close borders and deport people here without authorization.

Fears related to the economy can be persistent. We can address questions of culture and security only to have questions about jobs and trade linger. Business leaders, at the national or local level, can help Americans understand a changing community when they partner with other civic leadership. Speaking to American competitiveness and growth in a fashion that serves all workers, American and immigrant, helps people understand the value of immigration to the nation. When the message is immigrant-centric, people feel left out of the conversation, believing elites are looking for cheaper workers.

Changing Hearts and Minds

More in Common concluded, “To bring Americans back together, we need to focus first on those things that we share, and this starts with our identity as Americans.” Questions of race, religion, and patriotism led to competing frames that pushed people apart. But, “One belief that brings Americans together is a sense that the country is special.”

We observed that when Living Room Conversations participants with different religious or political beliefs felt that their individual concerns were being heard, the tension in their voices dissipated, and their faces brightened. The discussions turned towards solutions, not divisions. In our conversations, we saw the same theme More in Common found in their data: a need for new approaches and a different conversation on immigration that helps people come together.

Taken together, the Living Room Conversations left us with a powerful realization: American identity is being reshaped as perceptions related to culture, security and the economy are shifting. Quickly changing demographics are not solely responsible; the industries of the past are giving way to the industries of the future, and the transition from a post-industrial to a knowledge-based economy is disruptive. New technologies, social norms and conventions are accentuating the way many Americans view issues such as immigration. When it comes to identity in the context of culture, security, and the economy, there is both optimism and concern.

“It’s very easy to hate from a distance,” one participant in Spartanburg said. But as people get to know the immigrant family next door, at their child’s Little League games, or one pew over at church, they come to understand them, appreciate them, love them and value their individual contributions to the larger American story. The challenge in front of us is whether we can bridge the personal relationships with a broader perception of immigrants.

Which leads to the foundational question: What actually changes people’s hearts and minds? It is easy to assume, and a lot of social change campaigns do, that if you can change someone’s attitude or emotion towards something, you can change behavior. But that isn’t really true, or, at least it’s not the whole picture.

From the Theory of Planned Behavior we learn that campaigns that focus solely on creating an emotional reaction, shifting an attitude or even creating empathy, don’t tend to have sustained and lasting effects on behavior. In other words, the emotionally gripping story of a mother seeking asylum or a successful immigrant business owner offers a fleeting sense of what is possible. And in this media environment, that moment is quickly replaced by the next headline.

Taking a step back to offer an audience an emotion, attitude or empathetic moment connected to an underlying belief or value, allows for a conversation about change that can be sustained. And when that value or belief is connected to a person’s self-perception and connected to the norms of their community, there is potential for behavioral change.

The new normal is a fast changing, fast moving world that impacts the way Americans see themselves and each other. And, at least for the foreseeable future, the fears of migration and immigration will continue to be exploited for political gain.

Few politicians can step into this fray unless they are willing to cross partisan lines. Which is hard to imagine these days.

But local leadership — the pastor, the police chief, the local business owner – have the potential to bridge the divide. These are the trusted messengers who can operate within the networks of friends and family that are some of the most trusted places in society.

They are the local leadership with the trust and the credibility to help Americans understand the shifting nature of community in the context of global migration. They are trusted leadership who can meet people where they are, but not leave them there.

About the Author

Ali Noorani

Click here to download essay and view full footnote references. The author’s views expressed in this essay are his own.

you may also be interested in…

-

Community Impact / Report

-

Community Impact / Article

-

Community Impact / Article

-

Community Impact / Article

How Immigration, Faith, Neighborhoods and Quality of Life are Changing Across the Nation

As a new decade dawns, the American experience is often described as individualistic, isolated and increasingly digital, with traditional community ties fraying and fractured. But in fact, a strong sense of community remains core to the American experience and is simply showing itself in new forms.

So what is the future of communities? In looking for answers, Knight Foundation asked four leading scholars and community leaders to consider this question: “What is the most important trend that will transform how Americans think about community over the next decade?”

The common themes emerging from these essays are that high-touch tools requiring human interaction are critical to building trust, especially when people fear their neighborhoods are changing too quickly and their job security is at risk. Local leaders, not just those with formal roles such as the pastor or police chief, but business owners and community activists, can bridge those divides when they are seen as trusted messengers. And faith communities can remain places for spiritual growth and connection, even if it’s less about the Sunday morning service.

Americans crave connection, and neighborhoods and cities that provide opportunities for citizens to fully live a life of connection will thrive.

Four thought leaders examined trends they thought are the future of American communities – immigration, religion, civic engagement and quality of life. They wrote the following essays:

Out of Many, One: Immigration, Identity and the American Dream

The authors’ views expressed in these essays are their own.

You may also be interested in…

-

Community Impact / Article

-

Community Impact / Article

-

Community Impact / Article

-

Community Impact / Article

Knight Foundation asked four leading scholars and community leaders to consider this question: “What is the most important trend that will transform how Americans think about community over the next decade?” Jahmal Cole, Founder and CEO, My Block My Hood My City (M3), shares insights below. Click here to download and view all essays.

The future of “community” is rekindling the spirit of local organization. In Chicago, the most local form of community organization is the block club. On average, these block clubs consist of the residents of 35 homes. On my block there are 16 houses on one side of the street and 19 on the opposite side. Democracy and community within our city start at the block level. The more connected we are, the safer, happier, and healthier we are.

Grassroots Government by the People

For those of you who may have never heard of a block club, let me explain. A block club is a group of people who live on a specific city block (smallest area of land surrounded by streets) within a neighborhood. The primary purpose of block clubs is to improve the local quality of life through organizing and social action. They connect with each other to share ideas about what needs to happen to strengthen their neighborhood and find ways to combine their efforts toward making it happen. Lately, I would argue that many of these block clubs have lost their steam and lack a clear vision for community improvement. We need these community organizations, and we need them to innovate to keep pace with changing neighborhood conditions. Due to a lack of resources and opportunities, neighborhoods on the south and west sides of Chicago have suffered economic hardship and the loss of hope for themselves and their communities. As a result, these neighborhoods are plagued by what I call a poverty of imagination, or simply stated, a lack of ideas. Ideas are powerful tools! One idea can change the world.

Democracy and community within our city start at the block level.

We blame elected officials for community conditions: the neglected alleys, trash in the parks, high crime rates, and failing schools. This blame excuses a lack of personal responsibility. The reality is that the mayor doesn’t demand that you get to know your neighbors, but if you want your block to be safer, you must know your neighbors and work together to strive for better conditions. It isn’t an alderman’s job to pick up trash in our alleys and they cannot demand residents to do so. However, if you want to rid your block of blight and vermin, the demand is on you to take action and pick up that trash. Government is not a cure-all for every ailment in our struggling neighborhoods. To improve our quality of life, there must be personal accountability, initiative, creativity, and ideas. The purpose of block clubs is to create an organized environment that instills that spirit and capacity for action in its residents.

Embracing Social to Lead Local

Just as new leaders are elected based on the needs and vision of Chicago’s residents, a new style of leadership is needed at the local level to address the needs and vision of our communities. That style must include and embrace technology. What a time to be alive and organizing! There are technologies that allow leadership to communicate directly with their stakeholders. Chatbots allow them to communicate with followers and target their campaigns. Mobile devices enable immediate sharing of information, including livestreams and podcasts. Online surveys and polls provide interactive feedback from constituents, and social media sites like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram provide a wealth of social media influence and interaction to both leaders and their followers. President Barack Obama used social media to increase his visibility and win the 2008 presidential election. Of course, there are risks and downsides with this connectivity too. And many leaders don’t know how to use technology to effectively engage with the world. An online survey by Harris Poll showed that nearly 70 percent of leaders don’t know how to build a brand that a city can get behind. Communication and interaction are critical to the success of both leaders and organizations, including block clubs. These clubs are social groups offline, and they can be social groups online, as well. The organization I founded, My Block, My Hood, My City (M3) works to elevate these block clubs and their mission in order to promote peace and prosperity in Chicago’s under-resourced communities. M3 was born out of my love for traveling and helping people. I don’t think you can truly love helping people if you’re not willing to travel to them. You can understand and share another person’s feelings, but a true leader moves beyond empathy to compassion. Compassion entails not only sympathetically understanding another person’s distress but also having the desire to do something about it. I have empathy when I hear a snowstorm is rolling in, but it is compassion that makes me grab my shovel and clear snow on a whole block. I am empathetic about kids not having access to opportunities in Chicago. They’ve never been downtown and seen Lake Michigan, waved for a taxi or been in an elevator. Compassion drove me to get a 15-passenger van and start an Explorers Program so I can transport underserved youth so they can have these experiences.

Technology and social media provide our block clubs with a way to connect, communicate and interact. M3’s One Block at a Time uses Facebook to organize block clubs in Chicago. “One Block” currently has 50 block clubs chartered with M3, each with 35 members that represent the 35 homes on the block. The block club administrator, known as the block club captain, can disseminate information quickly, easily, and freely to those members as needed. Regular updates about block activities and issues are shared within seconds. Video chats can take the place of physical meetings, allowing more members access and the ability to participate and contribute to the issues at hand. They can take advantage of the M3 Facebook Page Units, where they can access heating tips during a polar vortex and find resources to assist during extreme heat waves.

M3 tutorials help residents start their own block clubs and find new ways to connect to hyperlocal civic organizations on Chicago’s south and west sides. We help them use technology to find and support volunteers, identify resources, share ideas, and seek advice. M3’s One Block at a Time program provides supports to them, including branding with new block club signs. These signs are designed by Chicago high school students and graphic artists, with positive and inclusive messaging, and installed by M3 staff. In addition, One Block at a Time organizes beautification projects, including alley cleanups, vacant lot and abandoned building maintenance, garden installation, and yard work and snow removal for seniors. This work incorporates M3’s full network of volunteers, Chicago students who are completing service hours and M3 Explorers interested in growth opportunities over summer break.

In the process of organizing block clubs, M3 also creates their Facebook group and trains the members of the clubs to use Facebook and access the features that are available, including sign up information and fliers to promote their club. We encourage civic advocacy, sharing how block clubs can advocate for necessary city services, including speed bumps, stop signs, street lights, and park repairs or maintenance. Technology and social media expand our outreach and ability to virtually travel to individual neighborhoods.

Through M3 and social media, I know I am not alone. There are residents, both within and outside these neighborhoods, who have the empathy and compassion to contribute to our communities and help solve our issues.

Block Clubs 2.0

Block clubs are not new — they have been instrumental in uniting neighborhoods for decades. In the next decade, technology will allow us to redefine leadership to create a playbook for community leaders. That technology is increasing every day, providing us with the space we need to unite and be innovative as we work together to address the issues and problems we face. One Block at a Time seeks to reimagine block clubs so they promote inspiring and positive messages, rather than restrictions, such as “no littering” and “no loitering.” By promoting positive messages, such as “Where all guests leave as friends,” we aim to create environments focused on “yes.” Positive phrasing reinforces positive attitudes and positive actions.

In the next decade, technology will allow us to redefine leadership to create a playbook for community leaders. That technology is increasing every day, providing us with the space we need to unite and be innovative as we work together to address the issues and problems we face.

Bringing block clubs into the 21st century means more than new block club signs; it means helping them use technology that will foster greater interconnectivity amongst their members. There is already plenty of technology in Chicago’s under-resourced communities. There are shot-spotters microphones on poles that record gun shots. There are blue light cameras that record and report criminal activity in the vicinity. There are cameras that identify vehicles exceeding the speed limit and speed cameras and red-light cameras that issue automatic tickets to those who fail to stop at an intersection. These technologies are being used reactively. While their purpose is intended to increase public safety and deter crime, there is concern that they do not deter crime, but merely encourage criminal activity to move down the block, out of the scope of the camera. In addition, they are viewed as a negative reflection of neighborhoods, labeling most or all of its residents as criminals, and because they are constantly recording everyone’s movements, they are considered to be a violation of privacy. Therefore, they are destructive to the psyche of the people who reside there.

I have been experimenting with ways to use technology constructively, using social media tools to build community, not to label communities or take valuable revenue or resources from them.

For example, on Feb. 9, 2018, there was a huge snowstorm in Chicago, and the city became quickly overwhelmed. I live in Chatham, on the south side of Chicago, where 60 percent of the residents are senior citizens. These seniors couldn’t shovel for themselves and were basically barricaded in their homes for day. Some had doctor or hospital appointments and/ or other important obligations, and they needed to be able to safely walk out of their homes and drive their vehicles. I went to Facebook to seek volunteer support. On that day, I saw the power of a single Facebook post.

My single Facebook post received 26,811 reactions (emojis), 1,842 comments (which I read), 5,960 shares, and 244 clicks to my website. It also captured the attention of local media and got over 26,000 shares once it was posted by WGN, a local Chicago television news station. The next day, over 120 people from all around the Chicago region, some even as far as Indiana, met me at the Chatham train station to shovel for seniors. It was an amazing day for not just the seniors in my community, but also for Chicago as a whole.

This example shows the power of technology and how important it is for local residents and leaders to understand how to use it. This technology could have been very useful in the 1995 Chicago heat wave, which led to 739 heat-related deaths in the city over five days. According to Eric Klinenberg, author of Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago, most of the victims of the heat wave were elderly and poor residents of the city, who could not afford air conditioning and did not open windows or sleep outside for fear of crime. The outreach and sharing of information about cooling centers and other resource via Facebook and social media might have saved many of those lives lost due to the extreme heat.

Let’s stay with the Facebook example. When it comes to community organizing, My Facebook Ads (campaigns that target specific Facebook profiles, depending on their interests, demographic, etc.) are customized calls to action, where I’m empowered to target a specific geographic region, specific age range, people who match our interests in community issues, volunteerism, civic engagement, and interest in using M3 volunteers to build coalitions across color and class in Chicago. We have volunteers from 60 of Chicago’s 77 communities. Many are Facebook users who learned about us through these ads. The increased technologies available on Facebook, as well as other social media sites, and technology that can be accessed through mobile devices allow leadership of organizations large and small to communicate directly with their following. I intend to increasingly make creative use of this technology.

Chicago has a reputation for being segregated and disconnected, but I believe strongly that there are so many people with good will and a desire to connect who lack the guidance, know-how, and platform to do so. I choose to use Facebook to connect the will to do good and the good that needs to be done. Our leaders need the capacity to choose and use technology constructively, to build communities through volunteer outreach, targeting specific demographics with specific projects, and creating strong and expanding online and physical communities to hurdle the socioeconomic barriers that divide the city. This technology includes Facebook, but it extends to other sites, including YouTube, Twitter, LinkedIn, Instagram, and others.

If used wisely, technology has the power to amplify community organizing and boost movements for social change. If Dr. King was alive today, he wouldn’t be able to accept any more incoming friend requests on Facebook. He would have reached his 5,000 connections limit long ago. Next to his 180 x 180 pixel profile picture would be a blue verification badge, letting people know that his profile is authentic. The custom banner for his public figure page would mirror his profile picture. His team would have surely figured out long ago that the Facebook cover photo size is 828 x 315 px, and they wouldn’t cut corners on this because the image size is important; if it’s wrong, it will reflect poorly on your brand. If the sizing is off, the images will become blurry. Dr. King would engage his online community daily with questions about issues and policies, and in this way, everyone would like they are a part of the movement.

Dr. King would be listed as administrator of The Southern Christian Leadership Conference page, but the actual page would be managed by a national team because it’s a nationwide organization. They would set up Facebook groups for each SCLC chapter in every membered city. These groups would provide a space to communicate shared interests with certain people. SCLC online talk or “chat” would center around local political advocacy, outreach programs, and bringing a voice to issues in both online and physical spaces. Each chapter would have its own group administrator, and the members of each group would be residents of each city. Admins of each chapter/group would use analytics like Group Insights to understand how members engage within groups, discover who the most active group members are, and learn which posts have the most engagement.

Now this functionality doesn’t currently exist, but Dr. King would work with Facebook to allow boosted posts within groups. Currently, Facebook only allows boosted posts from the main page, but not within groups. As a result, a great deal of important information from Dr. King and/or the national headquarter office could go unseen by group members, especially if there are thousands of folks in each group.

SCLC admins would have mastered Facebook ads and marketing. They would be able to create a targeted reach to members in their individual cities for a specific event without having to post the event on the main page. Dr. King wouldn’t be using Facebook boosts randomly — he would already be logging into his desktop and using Facebook ads as customized calls to action, targeting specific geographic regions, specific age ranges, people whose interests match community issues, volunteerism, civic engagement, activism, civil rights, human rights, causes. etc. I imagine Dr. King speaking with Nelson Mandela in South Africa on What’s App. But I believe he would be far too savvy to use this tool solely for text messaging friends overseas. He would take advantage of What’s App groups to conduct private meetings with these global leaders, national and internationally. What’s App allows you to see if a person read the message, as well, so it’s quite useful.

Facebook Pixels would be installed on the SCLC website along with search engine optimization. Blue Jeans technology would be used to livestream Dr. King’s presentation all over the world. Can you imagine Dr. King going live on Facebook from the March on Washington or the Edmund Pettus Bridge? If Malcolm X was alive, he would livestream his speeches from the Harlem Ballroom using Blue Jeans by Facebook.

I am sure Dr. King would be amazed by the technological tools and resources that are available to us today, and I’m just as certain that he would have taken advantage of them. Like me, he would have understood that technology provides us with a powerful tool to affect social change. It is an effective way to build both physical and online communities through sophisticated marketing strategies and the best tools available.

Unlike generations ago, our leaders today have to consider not just their physical presence and publicity, but they must also consider the social impact of their work and the massive, even viral, online presence they can build through that work. Human ideas can shape technology, but it is just as true that technology empowers our ideas. When the two join forces, the possibilities to impact change within a community or within the world are infinite.

People don’t need to feel isolated or alone in their desire to improve their lives and their neighborhoods. They are not one against many; they are one among many.

There are technologies in place that will allow networks of block clubs and their leaders, so they can share advice and mentor other new and/or existing block clubs. The SCLC used the tools and resources available to spread its message, vision, and mission. One Block at a Time will follow suit and continue to use technology and social media to expand our outreach and influence to bring prosperity and growth to the neighborhoods we serve. Positive actions and attitudes will only prevail if people are aware of them. There is power in numbers, and technology enables One Block to increase our following and support one resident at a time, one block at a time, and one community at a time. People don’t need to feel isolated or alone in their desire to improve their lives and their neighborhoods. They are not one against many; they are one among many.

Block clubs are governments by the people at the grassroots level. Larger governmental agencies are critical to us, and we are in need of their investment of time, money, resources, and ideas. However, resident investment in our own neighborhoods can produce improvements in many aspects of our lives, including our safety, crime rate, educational facilities, and the condition of our parks. We are aware of our problems because we are closest to them, and resident by resident, block by block, we can unite to find solutions to those problems by innovating at the hyper-local level.

Change and innovation start with individual residents. The policy makers in Chicago are temporary and will change with every election cycle. Problems in our local communities will outlive their terms of office. The real power doesn’t lie in government, but in the residents. Block groups provide them with the forum and means to be heard and to experiment and innovate — often with the help of technology — to ultimately find local solutions to local problems. Government agencies play a crucial role in creating an environment that will support this local innovation.

Communities need space for their voices to be heard and their ideas to grow — an online presence where they can be present, innovate, and develop solutions for the betterment of all. If we take the building blocks of block clubs to the next level by helping them create and sustain online communities, we can work together to make the changes that allow us all to prosper.

About the Author

Jahmal Cole

Click here to download essay. The author’s views expressed in this essay are his own.

you may also b e interested in…

-

Community Impact / Report

-

Community Impact / Article

-

Community Impact / Article

-

Community Impact / Article

Place and the Pursuit of Happiness, Upward Mobility and the American Dream

Knight Foundation asked four leading scholars and community leaders to consider this question: “What is the most important trend that will transform how Americans think about community over the next decade?” Ryan Streeter, Director, Domestic Policy Studies, American Enterprise Institute (AEI), shares insights below. Click here to download and view all essays.

Introduction: Communities and American Ideals

Public conversation about the future of communities is often dominated by debates about talent attraction, urban-versus-suburban development priorities, access and affordability. But any attempt to envision America’s communities of the future needs to expand beyond these narrow objectives and begin with the more fundamental ideals that unite and ground American society. Communities that hope to flourish need to allow their residents to achieve the American Dream of upward mobility. They should also enable the expression of self determination, unity amid diversity and strong familial and communal life.

More than abstractions, these ideals have practical consequences. For most, the American experiment is first experienced in the communities where they live, and their reasons for moving to, or staying within a community often have to do with how diversified and robust the overall experience of opportunity is. The ideal community, I will argue, is both competitive and desirable. It capitalizes on its distinctive qualities to compete with other communities for people, investment, and jobs, and it also offers a level of life satisfaction that makes its residents think twice before leaving. Most importantly, it caters to diversity of preferences and allows for individual realization of aspiration.

First, as knowledge-intensive enterprises continue to drive economic growth, thriving communities need to find ways to attract and retain workers with high degree of sociability. Jobs requiring high levels social skills grew by 12 percent between 1980 and 2012, and during that period math-intensive jobs actually shrank by 3.3 percent. Employers have increasingly demanded that jobs requiring high levels of cognitive ability be filled by people also possessing strong communication and social skills. Automation and offshoring have raised the demand for “new artisans,” workers who possess both technical and interpersonal skills. These socially skilled knowledge workers have congregated in knowledge centers across the country’s urban landscapes. Understanding the preferences of these workers, planners and city leaders can design and build communities that support them. Sociability and the types of communities that support it are important phenomena for urban planners and city leaders to understand.

The second trend is demographic. America’s population is defined by a growing aging population and a millennial generation even larger than the baby boomers. Since 2000, Americans over the age of 65 grew from 35 million to nearly 50 million, or from 12.4 to 15.2 percent of the population. As retirees grow in proportion to the U.S. population as a whole, so do retirement destinations, which grew by 2 percent last year. Older Americans as a group are wealthy, and yet they look to economize and stretch their dollars. Millennials, while commonly described as city dwellers who defy conventional aspirations for family and homeownership, actually have higher numbers in the suburbs, a trend that is only increasing as they age. Still, it seems that their residential preferences lean toward places with characteristics of urban lifestyles and amenities. To retain wealth and wisdom while attracting young talent that will fuel their economies, community leaders need to pay attention to the preferences and interests of both of these populations.

Finally, digital technology has given rise to what we might call “the preference economy” in which individuals have the ability to develop and pursue diverse interests and to associate with others who share them. The preference economy has helped to facilitate what some have called the “democratization of taste,” whereby formerly elite choices are available to the masses. The internet permits everyone to dive deep into our interests, refine our tastes, find others who share our interests and form a virtual community without ever leaving our home. Given the choice, we will also live in a place that matches our interests. The rise of the preference economy has created demand for customization in many spheres of life, including choice of community.

Getting the Basics Right: Why People Move and Why They Stay

If cities and communities are laboratories in which we pursue our basic aspirations for a better life, we should aim to understand how aspiration and preferences shape community choice. Why do people move to, or stay, in a community? The aspirations that guide people’s preferences and ultimately, choices should serve as a guide for policymakers, developers, and community leaders. What should a “policy of aspiration” look like?

Most residential choices are driven by “hard factors” such as jobs, affordability, safety, and good schools. “Soft factors,” such as parks, natural amenities, restaurants, and third places in which residents can socialize and pursue their interests, also play an important role in attracting and retaining knowledge and services sector workers and older people. Too often, however, enthusiasm for soft factors leads to a focus on design features — such as higher-density neighborhoods and mixed-use development — missing the hard factors that heavily influence most people’s residential decisions. The final, often neglected factor in commentary on urban development, is social connectivity, increasingly understood as key to growth and dynamism.

Hard Factors: Jobs, Affordability, Education

The communities in America with the fastest job growth are also the places in which workers can afford to buy a home or rent an apartment that matches their aspirations for a good life. Contrary to the urban booster myth that young people only want to live in dense urban areas, most upwardly mobile 25 to 34-year-olds seek less dense and even suburban-style communities. Major metro meccas such as New York and Los Angeles are losing population, while mid-sized metros with less density such as Austin, Nashville and Raleigh are growing.

Creative class types, it turns out, share the common American interest of a home and a yard more widely than is usually reported.

When young adults decide to settle down, they tend to leave higher-cost cities that seemed exciting just a few years earlier and head for lower-cost cities. Even tech jobs that do not need to be in Silicon Valley tend to migrate to more affordable cities with a promising quality of life.

Upwardly mobile 25 to 34-year-olds are a big part of the migration story. Their numbers swelled by 49 percent between 2000 and 2014, and there are now more of them living in Austin than in the San Jose metro area. And yet the total migration into the city’s center is miniscule compared to the growth of its suburbs. Between 2000 and 2012, a period of explosive population growth, 564,700 of the 588,000 people who moved to Austin located in the suburbs. The booming downtown that comes to mind when most people think of Austin’s dynamism only accounted for 1.6 percent of its growth during this period. Creative class types, it turns out, share the common American interest of a home and a yard more widely than is usually reported.

The outmigration of families from city centers to the suburbs when children reach school age is well-known. But it seems clear that if schools are important to a family with children, it is a significant factor in deciding where to live. Heterogeneity in school offerings is a net benefit for a community, as traditional public schools vie for students with charter schools, private schools, and non-traditional options such as online schools and homeschooling cooperatives. Good schools are a sign of local institutional health, which correlates with higher levels of social capital and community stability.

Soft Factors: Amenities, Recreation and Entertainment, Services

While hard factors such as economic opportunity and affordability drive basic decisions on where to live, amenities matter a good deal, especially with regard to elderly Americans, college graduates, and people working in knowledge-intensive occupations. Natural amenities such as temperature, hills, and proximity to water, have been found to matter more to older people, while constructed amenities such as coffee shops, entertainment venues, bars, and shops, matter more to college graduates and knowledge workers. The happiness of older residents of a city has is also associated with good government services such as public safety and schools, while the happiness of younger people stems from access to cultural and recreational assets. Workers in professional services and knowledge sectors have diverse preferences when they choose where to live depending on life cycle and personal interests. These findings suggest that a future-oriented community should provide diverse residential and lifestyle options for people working in growing sectors of the economy rather than catering to the narrow preferences of knowledge workers.

Another detailed study of 164 metro areas found that mid-size metros (cities between 500,000 and 2.5 million residents) had a greater presence of college-educated workers and higher overall population growth when certain quality of life factors were present, defined by measures of crime, housing costs, and diversity together with cultural amenities. The effect was more limited for smaller metros between 250,000 and 500,000 residents. The study suggests that young talent considers amenities along with housing affordability when moving to mid-size metro areas.

Social Factors: Networks and Upward Mobility

Social relationships and networks are the final factor shaping residential preferences. They do not fit neatly into the concepts of hard or soft factors. The presence of social and professional relationships affects people’s happiness with their location and their relocation decisions. A study of 13 cities in Europe found that professional and social connections were a powerful factor in location decisions, followed by hard factors such as job availability and quality. Soft factors such as amenities and cultures of openness and tolerance mattered much less. Research has also shown that social connections matter a great deal to economic opportunity, including for low-income people; more social connections increase chances of getting a job, and better-paying jobs.

In the economic geography of today’s America, these networks are unevenly distributed. People living in high-growth areas are not only highly educated and well-paid, they are also highly networked. They have access to information about opportunities and live and work in networks of relationships that augment this information. Their networks open doors and expand and accelerate options and opportunities. Many studies have also shown, though, that lower-income people with richer and more extensive networks fare better than those who do not. Conversely, high-achieving lower-income young people often miss opportunities to advance their education and economic position because of a lack of connectivity. The problem is one of scale, namely that even lower-income families with good networks are not as equally connected to opportunity-creating networks such as institutions of higher education and professional networks as higher-income people who take them for granted. The challenge for cities of the future is to build bridges between less-networked communities and populations with those institutions and communities that are rich in networks leading to a wide range of opportunities.

Competitive and desirable communities will therefore strive to create new forms of social and vocational connections. New tools are emerging to help better understand which jobs requiring which types of skills are in demand. Future-oriented community leaders should strive to be the first to find ways to provide that information, along with guidance on the educational and training institutions that provide requisite skills training, directly to aspiring workers, their families, and their teachers and coaches. Community leaders can also do more to connect lower-opportunity with higher-opportunity neighborhoods through job fairs, community festivals, and transportation between them. They can also work to improve the ability of institutions of higher education, including community colleges and technical training institutes, to build stronger networks with employers and aspiring learners in other cities through digital tools. Not only would such a forward-looking community benefit its residents, its reputation for connectivity could become an attraction for migrants from other places.

City leaders can promote the growth of social networks by involving civic and professional associations in their planning. The best way for local organizations to grow and work with one another is to be given an opportunity to do so. Rarely can such activity be mandated or overly engineered. Whether it is a public health campaign or an initiative to boost the arts in a community, private and public sector leaders should invite not only the participation but the leadership of community organizations with direct ties to neighborhoods and households, such as religious organizations, schools, neighborhood-focused community groups, professional associations and locally-owned businesses.

Human Scale and Happiness

The preference economy, the need for greater connectivity, and even the fundamental tenets of political philosophy suggest that the competitive and desirable community of the future will be on a human scale. Human beings are communal – even tribal – in nature, and our happiness is closely tied to the strength of our community ties. Cities and towns that figure out how to provide greater options for associational life and work-life balance will be more competitive and desirable than those that do not. Cities that figure out how to create living environments at human scale will attract new residents. But the notion of human scale is usually missed in analyses of hard and soft factors.

The Importance of Life on a Human Scale

The value we attach to smaller-scale communities is a deeply rooted element of the human condition. Plato and Aristotle both grappled with the proper size of a city-state because a successful polity depended upon relationships between governing and governed; among people who know each other and can hold one another accountable. This is a central argument in the Federalist Papers; the American republic could work at a large scale only with a proper system of checks and balances. James Madison believed that through a proper set of constitutional checks and balances in a federal republic, small-scale polities could live side by side and form a larger, coherent whole. Unity amid smaller-scale diversity is a fundamental American principle.

These and other philosophers were concerned with the idea of happiness and the preconditions for human flourishing. They observed that people are at their best when they are fully functioning members of communities in which their voices, opinions, and actions matter. Their insights have been confirmed and furthered by social scientists and economists more recently who have found, for instance, that there is a limit to the number of relationships each of us can manage, and that we derive our greatest sense of purpose and happiness from family, community involvement and relationships, religious engagement and work. Additional studies have found that regions with multiple local governments fare better economically, and Americans trust their local governments significantly more than the federal government or even their state governments. A recent survey showed that Americans in every demographic category derive a sense of community more from their city or neighborhood than their political ideology or ethnicity.

Human beings are communal – even tribal – in nature, and our happiness is closely tied to the strength of our community ties.

Districts matter

To the extent that people have a choice, they typically prefer communities in which school, work, grocery shopping, hanging out and community membership are proximate and in balance with each other. The “high street” in London is a quintessential instance of how communities within a large metropolitan area are anchored by unique, core set of community characteristics. High streets, equivalent in some ways to an American urban Main Street, anchor the retail and social life of particular districts within the greater London metro area. Each district and its walkable high street have unique personalities and identities. They create a kind of village within a large global city with which residents identify. Any large city with strong, distinct districts can be analyzed similarly.

One way to evaluate the human scale of a place is by assessing the walkability of a neighborhood or district. There is evidence that people prefer living in communities in which services, amenities and key institutions are proximate and even reachable by foot. A kind of “village instinct” seems hardwired into us. Given a choice, most people prefer to live in places that have some sense of a physical center in which life’s essential activities — work, school, religious and civic spaces — hang together. The success of new urbanist and mixed-use real estate developments on grid-patterned roadways is further evidence for the power of these preferences. Studies of various cities have found that all else being equal, home buyers are willing to pay more to live in neighborhoods marked by connected streets and a mix of residential and commercial uses. They will also pay more to live closer to the central business district and to shorten commute times. Home values increase the closer they are to core community amenities such as grocery stores, parks, schools, hardware stores, and so on.

That neighborhoods with mixed uses and tighter connectivity between core amenities and services correlate with higher home prices will not surprise longtime readers of Jane Jacobs’ views on sidewalk life in cities. Communities are more desirable when the basics of everyday life are all around us and nearby, rather than scattered across disconnected landscapes. When all else is equal, people prefer a sense of community in the built environment. This does not always have to take the form of village-like, walkable neighborhoods. It is possible to blend together Americans’ penchant for detached single family homes and automobiles, as numerous new urbanist developments have done. Studies have shown that proximity to Walmart raises home values, just as it does in neighborhoods close to a Whole Foods or Trader Joes.

In summary, when work, play, relationships and leisure “hang together” in a community, people generally fare better by any economic or social measure we value.

The Multi-Centric City

What are the lessons that community leaders should learn from insights into the virtues of smaller-scale social and political organization? The short answer is that cities should aspire to be “multi-centric,” that is, organized not only around the older urban core, but around local districts throughout the larger community for several key reasons.

First, diversity of interests and preferences is here to stay. As taste making has become both more democratic, diffuse, and particular, a competitive and desirable community will incorporate such proliferation into its design and structure. A multi-centric city with multiple uses within each of its “centers” helps to enable such diffusion and increases the likelihood that people with shared particular interests can be together socially, professionally, and residentially.

Second, increasing social connectivity allows for the spontaneous production of goods that are often better than those planned in advance. Increasing opportunities for nonprofits, associations and local businesses to join and lead initiatives aimed at the public good increase civic connectedness. Doing so locally within the larger community does so even more. Ensuring that local land-use allows for entrepreneurs, businesses, and residents to mold their particular district in unique ways promotes interaction and creative adaptation. Top-down planning cannot achieve what socially and professionally networked individuals can.

Third, keeping costs low and opportunity high will create the conditions for flourishing across a diverse set of local communities within a larger polity. The story of growth among cities in the south and west over the past few decades is very much a story about the balance between economic opportunity, new development, and affordability. As we have seen, counter to urban legends that abound, 25 to 34-year-olds tend to move to less expensive, opportunity-rich places as they move into the phase of life where one begins to make longer-term plans. On the other end of the life spectrum, an active class of older Americans also values affordability. Another added value to the multi-centric city is the options it makes available to an aging population as they downsize, move closer to core services to become less auto-dependent, and so on. Keeping the wisdom and wealth of aging people in a community should be a priority.

The successful community of the future will be multi-centric, meaning that as a city grows, it should not put all of its eggs in the “downtown” basket. It should have multiple downtowns, so to speak. Community leaders should obsess about districts rather than downtown-versus-suburbs calculations. Suburban communities should increasingly offer urban amenities such as festivals, food, and fun, while urban communities should offer suburban goods such as good schools, safe streets, and new housing.

When work, play, relationships and leisure “hang together” in a community, people generally fare better by any economic or social measure we value.