Welcome to the 14th annual Knight Media Forum. For all that time, it’s been my privilege to lead Knight Foundation, dedicated to strengthening democracy by supporting informed, engaged, and inclusive communities.

No surprise: this year’s virtual Knight Media Forum is unlike any that came before. In years past, we got together in Miami and benefited not just from a range of insightful speakers and provocative panels, but from the serendipitous conversations that sprang up in hallways and over meals, perhaps even poolside.

This year, of course, we’re missing that in-person connection and spontaneity. And this is the first time I’m welcoming you without a tie.

But our first-ever virtual Forum offers something else, and it’s good: The chance for more of you to participate. Last year, 550 people joined us in-person, and this year we’ve got more than 3,300 of you registered.

Welcome.

For those of you who are new to the Forum, let me share some history and context.

Jack and Jim Knight ran a newspaper company in service of informed and engaged communities. It grew into one of the country’s largest and most successful news companies — a collection of community-minded local papers, focused on quality journalism, good business practices, and the intelligent application of technology, from the telephone in the early part of the 20th century to their significant investments in electronic media that later became digital.

The Knight brothers started Knight Foundation to support journalism and community. They left it to their successors to determine how best to do that, because the key to their success had been to evolve and adapt their business to respond to changes in society. They said their foundation should do the same.

This event is a good example of that. It began in 2007 as the Media Learning Seminar, a series of conversations about media with the goal of engaging community and place-based foundations in meeting the information needs of their communities.

At the time, Facebook was three years old; Twitter was one; and only a month before the first seminar, Steve Jobs had revealed the first iPhone. That’s how long ago it was.

The weakening of the business model that long funded quality journalism was well underway — but the collapse, especially at the local level, was still in the future. Fourteen years later, the media business has become infinitely more complex, and local news has weakened or even disappeared in much of America.

At Knight Foundation, we’ve chosen to focus on finding sustainable models that will deliver consistently reliable news digitally and locally. We made that choice because digital is where the crowd is, and because local journalism is a way to build community cohesion and community bonding. Good local journalism is also how you build trust in institutions, including in media itself. A citizen can trust local news—but they can also verify. They need only step outside their homes to judge the quality of the report.

Over the past fourteen years, we’ve made hundreds of grants in support of news experiments around the country. We’ve supported organizations like Texas Tribune, Online News Association, and ProPublica from their start.

We supported others soon after their launch, like The Voice of San Diego, MinnPost, and the New Haven Independent.

More recently, we’ve been glad to support the Salt Lake Tribune’s conversion to nonprofit ownership and to form a partnership with the nonprofit Lenfest Institute in Philadelphia.

And we’ve also funded newer models, like City Bureau in Chicago and Outlier Media in Detroit, and we’re paying close attention to newer experiments like the ones being organized in North Carolina, Baltimore, and other places.

Encouraging this kind of exploration is very much our tradition at Knight.

Local funders like community and place-based foundations have been critical to this work over the years. We’ve seen many different types of foundations make strong stands for local news and information, and I’ll give you just a few examples:

- For the next several years, the Wichita Community Foundation will invest the majority of its discretionary dollars in a News and Information Initiative

- The Miami Foundation, helped establish the Esserman-Knight Journalism Awards, honoring public service reporting in South Florida

- The Colorado Media Project, a funders’ collaborative, supported by the Gates Family Foundation, created a COVID-19 Coverage Network connecting dozens of newsrooms across Colorado.

- The Cleveland Foundation and the Akron Community Foundation have supported the Community Information Needs Collaborative to give microgrants to journalists.

- Both foundations also supported a “City Scrapers” pilot by City Bureau journalists, making it much easier for people to monitor and analyze local decisions.

While we at Knight are mainly focused on not-for-profit organizations, we’ve also supported journalism done by for-profit newsrooms, and have strongly supported legacy news organizations as they shift to digital.

This work—whether for-profit or non-profit—has never felt more critical. One reason for that is our country’s experience over the last year. The pandemic and the social and political upheaval of 2020 helped showcase the value of local news.

Local news organizations connected people to food distribution sites, monitored local case counts and hospitalizations and told us where to get tested and, later, where to get vaccinated.

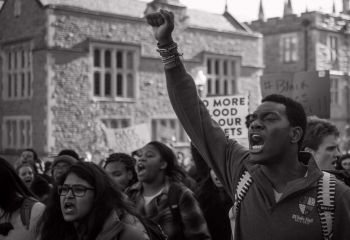

Local news covered protest movements, sharing otherwise untold stories of racism in our society and of local responses to the killing of George Floyd.

Local news explained unemployment benefits and told stories of small businesses finding ways to get through the troubles of shutdown. And local news told stories about local elections run smoothly, at the same time as a remarkably volatile national campaign.

When the world seemed to be falling apart, local news helped hold us together.

That’s encouraging—but as we all know and appreciate, local news won’t thrive if the business model isn’t sustainable, if the technology isn’t what the audience demands, and if the journalism isn’t reliable.

Great local news organizations have long been built on a three-legged stool: reliable journalism supported by a sustainable business, using the right technology.

To be independent, news organizations must be sustainable, and to serve the community, they must reflect it. That means telling the story of the whole community, not the story of one part or one class, one gender, one race or ethnicity. It also means telling stories that make us flinch, including directly addressing the reality of racism.

Past KMFs focused on using technology to inform communities; this week we’ll also discuss the impact of that technology on our democracy — and what we might do about it.

Knight does not — and has not pretended to — have all the answers to misinformation, privacy loss, or the antitrust issues arising from the enormous power of behemoth corporations that were in their infancy when we started this forum. But over the past two years, we’ve invested $50 million in research — at close to 60 universities, research centers and think tanks — to inform current and future debate over technology policy.

We believe the best way to solve problems is to explore them from many perspectives. And you’ll hear from some of those Knight-funded scholars this week.

Technology has also amplified tensions between freedom of speech and efforts to build a more diverse, equitable and inclusive society. Knight strongly supports, as Jack Knight did, the First Amendment’s edict that Congress shall make no law abridging free speech and free press. But the history of the First Amendment is full of nuance, and is influenced by what is going on in society. And not all free speech issues are about government.

For example, our research shows that a majority of college students believe free speech sometimes conflicts with diversity and inclusion. We’ve been surveying high school students’ attitudes toward the First Amendment since 2004, and we’ve seen that, starting in 2011, a gap opened between white students and students of color, as well as between male and female students, over whether the First Amendment goes too far. This, of course, at a moment when social media had become ubiquitous. It’s not unreasonable to speculate that high school students most likely to encounter abuse on social media — that is, students of color and young women — might be conflicted about free speech. That’s a problem for society.

The specific issues may vary, but the tension between these principles isn’t new. They flared during various wars, periods of national isolation, the Red Scares of the ‘50s, the Civil Rights Movement of the ‘60s, and they are, once again, now in tension. Sometimes the tension was resolved by recognizing that you couldn’t yell “fire” in a crowded theater. Other times it was resolved by new standards, as when the Supreme Court created a new test to prove libel of a public figure in New York Times vs. Sullivan.

These norms and laws require periodic revisiting. Given the current moment’s combination of social and tech upheaval, it’s time for society to review and update our guidelines, our limits, and our understanding, for the digital age. That’s why, in part, we created the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University.

At Knight, we have traditionally opposed government control of content. As a society, the United States moved away from that sort of censorship in radio and television, and we’d hope not to see it crop up again online. But our present struggles test that view.

When have we ever seen more widely and easily disseminated racist commentary, cloaked as free speech?

When has so much mis- and disinformation spread so quickly?

When have words or videos on a screen led Americans to assault the Congress of the United States?

Such a moment demands not just the recitation of principles, but a careful examination of how those principles have played out, and a thoughtful evolution of the application of those principles to fit the times, the challenges and the opportunities.

Through these 14 years of the Knight Media Forum, we’ve gathered to engage philanthropy in the future of news and the future of communities. We didn’t tell them what to think or what to say. We wanted them to consider our goal of an informed citizenry and engaged communities, the keys to a more effective democracy. And we are gratified that so many have.

We didn’t imagine how fast the old news models would decline, nor how fast the new digital platforms would grow. But, throughout, we have remained committed to the three unshakable beliefs: that free expression is a bedrock, that an informed citizenry is vital to democracy, and that communities are strongest when they’re engaged, equitable, and inclusive.

We believe in more experimentation, more exploration, and broad inquiry in the search for solutions.

Over the next three days, we will do what the Knight brothers believed in and what Knight Foundation has done: Engage people of good will, hear a variety of viewpoints, discuss, provoke, and ultimately both help inform citizens and policymakers and identify better ways to inform citizens and communities.

The path toward a more effective democracy is based, as it always has been, on a better informed citizenry. We seek sustainable models that will deliver local, consistently reliable news and information on digital platforms so that, as Jack Knight said in a speech to Akron business leaders 65 years ago, “the people may determine their true interest.”

Sixty-five years later, we find ourselves at a moment of “true interest”—a period in which the urgency and necessity of local news has never been clearer. It is up to all of us to meet the challenge of the Knight brothers’ ambition, and to spur the revival of local news and information, toward a more effective democracy.

That is what we’re here to do.