‘Architectural Imagination’ exhibit presents an array of visions for Detroit

Since becoming the first U.S. city to receive a UNESCO City of Design designation, Detroit has been abuzz with the potential of design to shape the future of life in the city. From the 2016 Detroit Design Festival—which included a two-day summit of panel discussions about the many concerns and influences of a design-based approach to social and cultural intervention—to anticipation of the return of DLECTRICITY in the fall of 2017, Detroit has had design on the brain. These forays into Detroit’s conceptual potential have not merely been restricted to local reflection; as Detroit joins a cohort 47 of cities in 33 countries around the globe that form the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), it is more than ever the focus of international attention. And the Detroit Creative Corridor Center, a nonprofit group that acts as the steward of the city’s UNESCO designation, received $1 million from Knight to support a 10-year vision of the metropolis as a UNESCO City of Design.

This attention was recently crystallized when Detroit was honored as the representative city for the United States Pavilion of the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale. Collectively titled “The Architectural Imagination,” the exhibition featured the works of 12 teams of architects, selected from more than 250 submissions, and presents a version of Detroit visible through a highly imaginative lens. Following its run at the Biennale through November of 2016, the exhibition has come to the MOCAD (a Knight Arts grantee), where it will be on display through April 16.

This dense and fantastical exhibit features projects proposed around four sites—a section of the Eastern Market/Dequindre Cut area; locales within Southwest Detroit, colloquially known as Mexicantown; the city’s central post office, located on Fort St. and abutting the Detroit River along its deactivated southern face; and the Packard Plant, a former automotive manufacturing facility, and the single largest contiguous industrial ruin in the United States. With these areas as their jumping off points, architectural teams from around the country presented a dazzling array of models and visualized data.

In her introductory essay for the exhibition catalog, co-curator Cynthia Davidson characterized the idea developed by herself and co-curator Mónica Ponce de León as “something yet unseen and something that only an architect would imagine.” Certainly, the Tomorrowland-like displays demonstrate an abundance of imagination, not to mention models saturated with satisfying details and visually engaging surfaces.

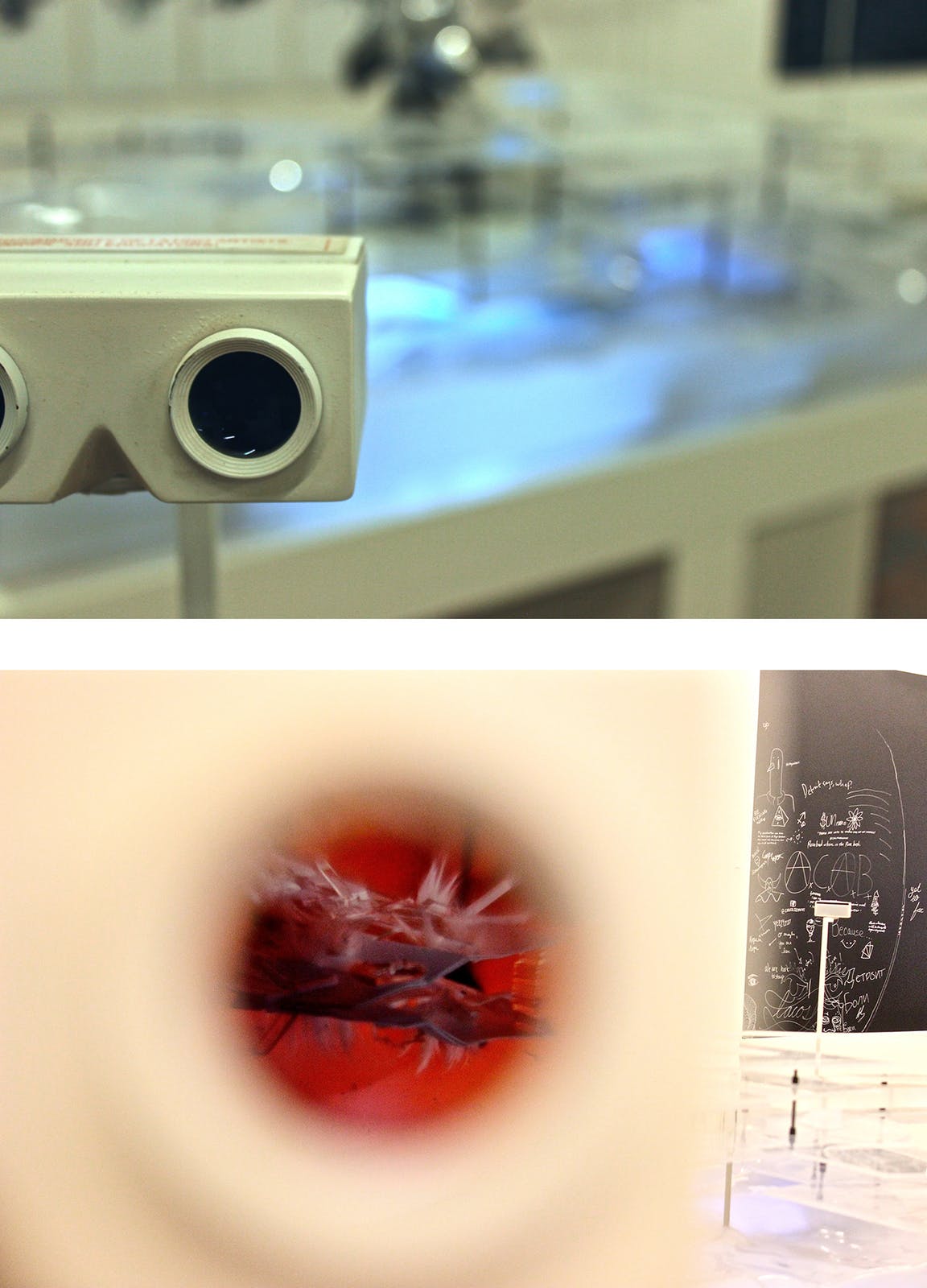

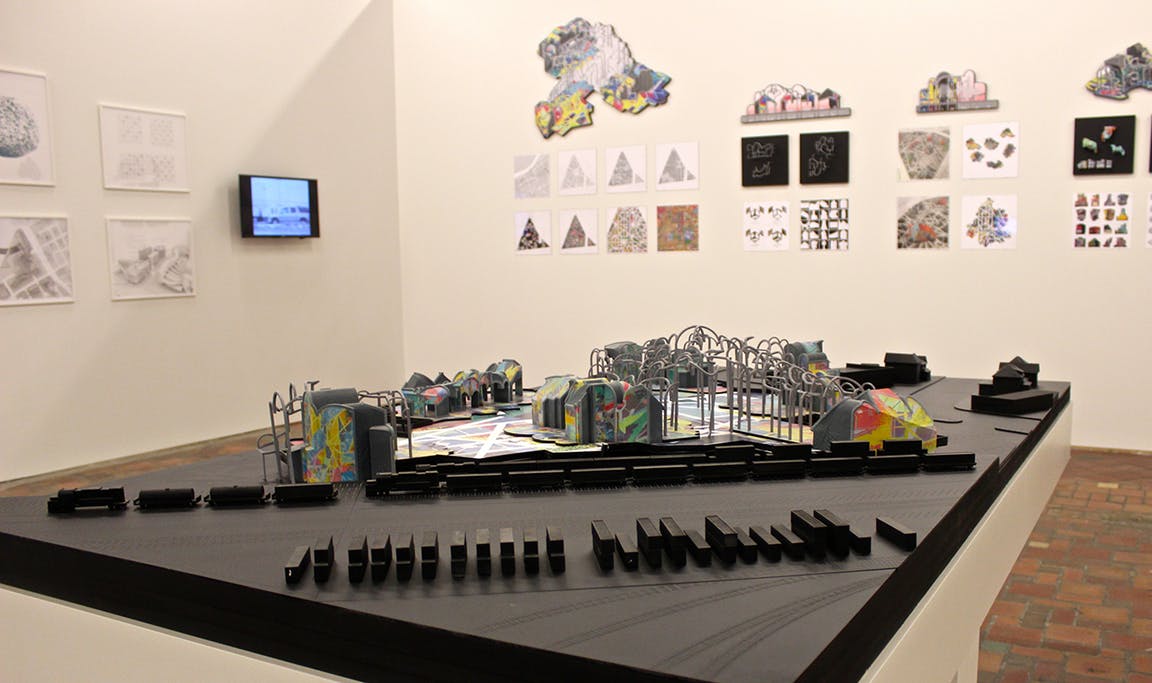

Mexicantown seems to be the site with the most radical and abstracted experimentation. A project by Marc Scogin Merrill Elam Architects, “A Liminal Blur,” presents not so much a building as a visualization of the site, with different aspects of the topography and neighborhood character represented by floating ribbons and planes of Plexiglass. Surrounding the display are plastic viewfinder-like glasses mounted on stands—when the visitor directs his or her view of the project through the glasses, they shift into a wildly diffracted and colorful perspective. Another Mexicantown project, “The New Zocalo”—designed by Los Angeles firm Pita + Bloom—presents an “urban platform” or elevated plinth. The display, which is dotted with a series of small, colorful and semi-open structures, connected by fanciful archways, suggests a village made of multi-dimensional graffiti.

The look in Corktown is more aligned with the traditional architectural love of clean, modernist building complexes. One of Detroit’s oldest neighborhoods, full of mixed ex-industrial facilities punctuating streets with quaint historic housing stock, Corktown is a high-demand market, and perhaps for this reason, there is a greater willingness to propose elegant high-rise complexes along the waterfront. The proposal by the Houston-based firm Present Future seems to nod to the vision of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe—a pioneer of mixed-use housing development in Detroit—with clean timber construction and large open areas with neat rows of trees. BairBalliet, a team from Columbus, Ohio and Chicago, envisions the Corktown site as “The Next Port of Call,” with a series of “Star Trek”-ish white and gold-toned buildings accessible both by land and by a series of canals in conversation with the Detroit River.

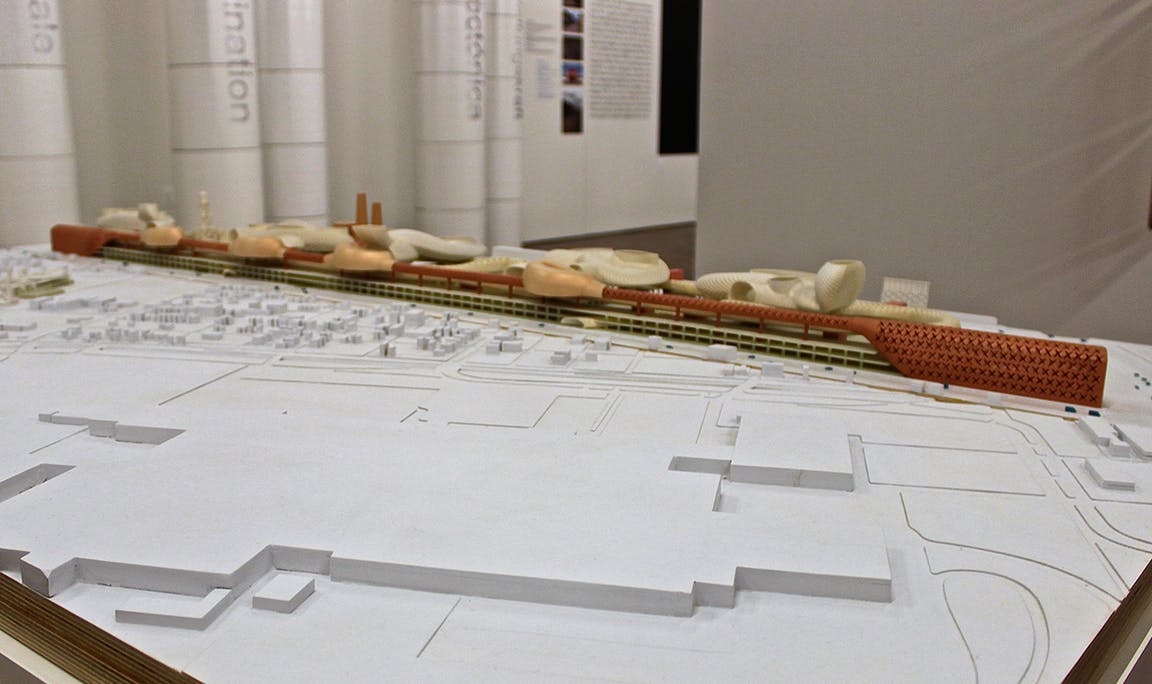

The Packard Plant, which continues to atrophy into its bare structural forms through decades of neglect, provides a space for some differing takes on Detroit’s geology. Both “Detroit Rock City: An Urban Geology” by Stan Allen Architect, and “Detroit Reassembly Plant” by T+E+A+M in Ann Arbor, Mich. are concerned with strata. Stan Allen’s project presents a clean, sprawling and flexible proposal, with open-frame mega-complexes standing over a mélange of little, individual concerns—represented in the model world as neutral shapes more than specific buildings. T+E+A+M’s project is focused on the Packard site’s potential for material salvage and repurpose, and to this end presents a fascinating display of “core samples” and a model that reconfigures these base components into more primitive structures, a kind of caveman-moonbase. Perhaps because they are based with greater proximity to Detroit, T+E+A+M’s presentation stands out among the projects as the one that feels the the most in touch with Detroit’s existing aesthetics and scrappy DIY spirit. Much more so than the “Center for Fulfillment, Knowledge, and Innovation” by Greg Lynn Form, which lays out a fantastical strip of spidery, open-weave building forms, with a clinical science fiction aesthetic abetted by the model’s obvious construction through 3D-printing.

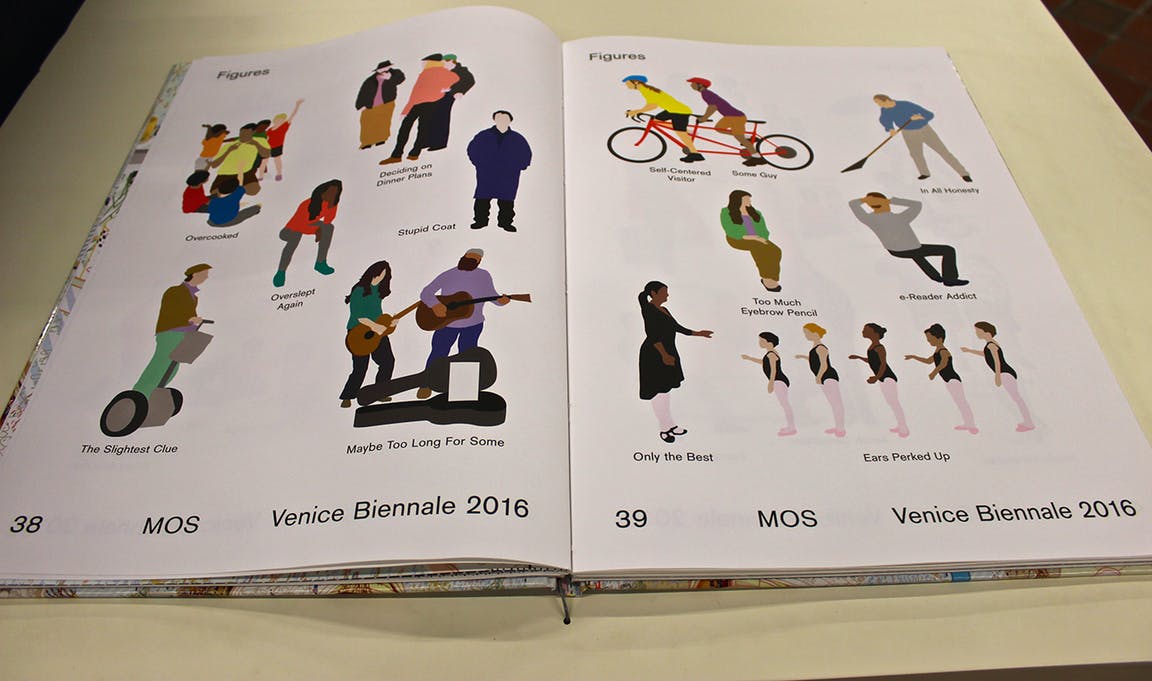

Over at the Eastern Market site, things start to get intensely imaginative. The Marshall Brown Project presents “Dequindre Civic Academy”—a towering Jenga-like structure that houses an imagined educational institution opening in 2026, with the ambition of serving the “physical, social, cultural and intellectual development of the city’s children, from birth to adulthood.” While the megastructure is delightful as a thought experiment, one struggles to imagine everyday Detroiters—or indeed, anyone with a healthy suspicion of science-fiction “educational centers”—sending their children to an institution to serve their needs “from birth to adulthood.” The project seems to propose a “cité within a city,” a complex so complete, it serves basically all the desires of the individual with no need to ever leave…a foundational concept that feels difficult to swallow without a touch of apprehension. Likewise, the New York-based firm MOS presents a project for this site titled “A Situation Made from Loose and Overlapping Social and Architectural Aggregates,” that goes so far as to delineate a set of character types populating their model. How considerate of them to go so far as to imagine the entire population, along with the facility.

But, after all, speculative architecture is the watchword of this—and arguably, all—high-profile architecture exhibition. We are not dealing so much in present realities as abstracted futurescapes, and “The Architectural Imagination” presents these in abundance, with no lack of aesthetic delights for the visitor. For an examination of design-based explorations of Detroit’s realities, we can look forward to the incipient opening of “Footwork: The Choreography of Collaboration”—a vision of collaborative design and innovation featuring the work of more than 60 individuals, collectives and corporations, on the topic of evolving work practices. The exhibition, which was also supported by the $1 million Knight grant and is traveling from Detroit to be shown as part of La Biennale Internationale Design Saint-Étienne 2017, was curated by Public Design Trust, as a subsidiary of The Work Department, a women-led social innovation design firm. This is the 10th installment of the Saint-Étienne international design show; it runs from March 9-April 9, with the theme of “Working Promise—the mutation of work.” “Footwork” deals with the intersections of design and working process with dozens of existing Detroiters, presenting a vision of Detroit innovation that is no less dazzling for being real rather than imagined.

With so much to recommend Detroit, locally and abroad, there is little doubt that some of these bold future visions will begin to translate from imagination to reality. There is no better time to visit the MOCAD and see how Detroit is being featured in the collective imagination—and with another round of the Knight Arts Challenge just around the corner, to think about how your vision can help shape it.

-

Arts / Article

-

Community Impact / Article

-

Community Impact / Press Release

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·