Detroit demonstrates the power of democratic design on an international stage

When Detroit Creative Corridor Center (DC3) began the lengthy and involved process of applying for UNESCO City of Design status on behalf of Detroit—a goal that was successfully achieved at the end of 2015—they did so knowing it would help centralize the role that design plays in shaping cities, and the lives of their citizens. Their efforts were bolstered by $1 million in new funding from Knight Foundation to help engage community members in urban revitalization that leverages Detroit’s design legacy and creative industries.

“Applying for the UNESCO designation was one of the long-term goals identified by the Detroit Creative Corridor Center’s founding director, Matthew Clayson, when the initiative launched in 2011,” said DC3’s director of advocacy and operations, Ellie Schneider, in an email interview. “DC3 spent several years developing programming and building partnerships locally and within the UNESCO network to make a case for Detroit’s membership in the Creative Cities Network. Applicants must demonstrate a legacy of design, show that there is an active design community today, and demonstrate potential for design to foster sustainable, equitable development for the city moving forward.”

The success of this effort has created a ripple effect within Detroit, as well as thrust the city and some of its foremost innovators onto an international stage. Detroit was the focus of the U.S. pavilion at the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale (the results of which are now on display at MOCAD through April 16) and was also the invited guest city at the 2017 Biennale Internationale Design Saint-Étienne. The festival runs for a month in the French City of Design, closing April 9, and the opening weeks have featured presentations, panel discussions and performances involving more than 60 members of a Detroit contingent. This motley crew included entertainment justice practitioners, urban farmers, curators, artists, members of city government and, of course, the exhibition-makers responsible for the three main Detroit showcases: independent design duo Akoaki, creative infrastructure-builder Creative Many, and social innovation curatorial team Public Design Trust.

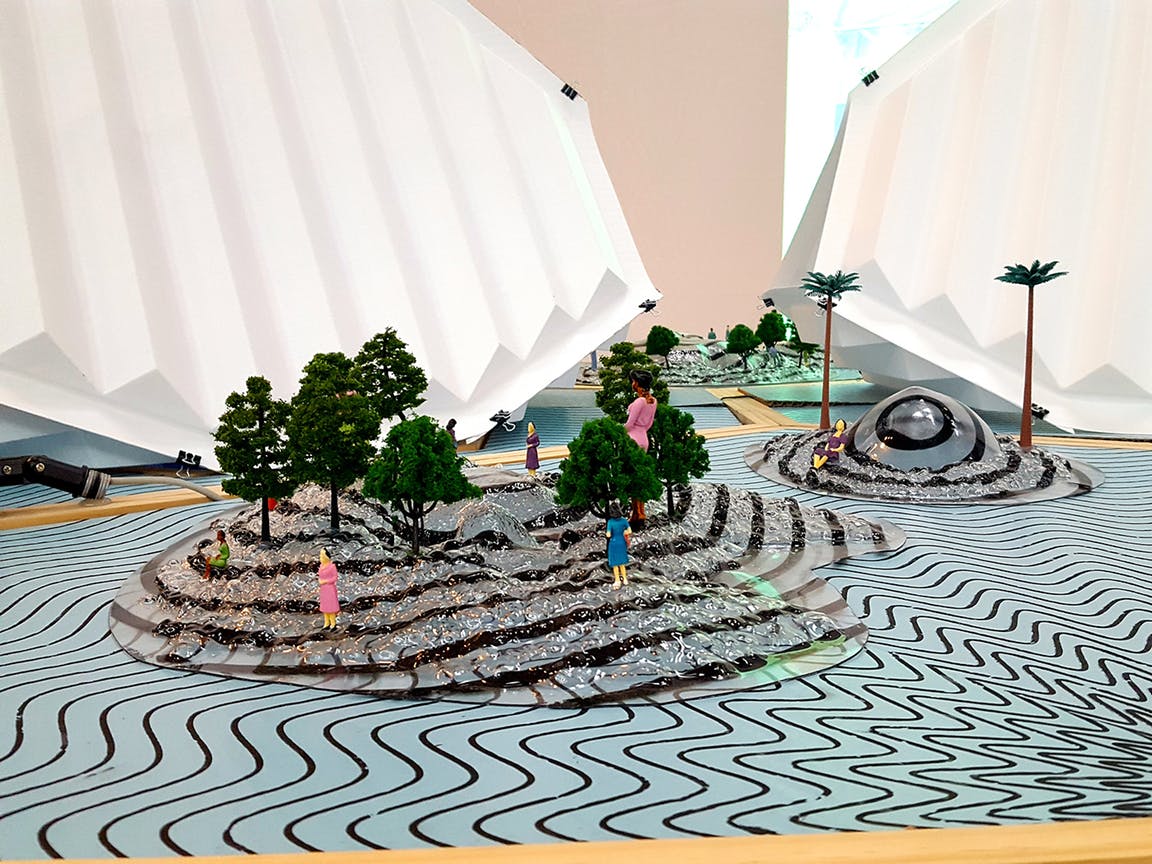

The invitation to the biennial came under the auspices of the work Akoaki—individually known as Anya Sirota and Jean-Louis Farges—has done in partnership with the Oakland Avenue/North End neighborhood. Their rhizomatic design interventions include the Afrofuturism-styled “Mothership” at O.N.E. Mile; stage sets used by Knight arts grantee Detroit Afrikan Music Institute; and a gate designed for the Detroit Culture Council, which can be affixed to existing facades to indicate a council gathering. These three “urban markers” were on display in Akoaki’s exhibition space, the “Out of Site” courtyard. In a biennial that was generally crammed to the brim with densely curated exhibitions showcasing international artists and designers meditating on the theme of “Working Promesse—Shifting Work Paradigms,” Akoaki’s space demonstrated the quiet confidence that Sirota and Farges have in their work. In contrast to the main exhibition hall, practically splitting at the seams with conceptually dense design statements, the “Out of Site” courtyard created an activated and welcoming space for audience engagement—design that considers people and invites their participation, rather than imposing conditions upon them. At a time when cities are looking increasingly to create dramatic change to their urban landscape, Akoaki offers an alternative to giant glass buildings and new development as economic drivers, instead demonstrating the power of design to do a lot with minimal, existing elements.

Rather than pack the conference with objects, Akoaki leveraged their resources to bring dozens of Detroiters to Saint-Étienne, reinforcing the oft-overlooked notion that Detroit’s primary resource is not its abundance of vacant land, but its incredibly resourceful and irrepressible citizenry. But lest anyone think that this wealth of creative innovators produces no tangible results, the Public Design Trust presented “Footwork,” a more conventional showcase of collaborative design, as practiced on the ground all over the city. The eight-person, all-female team assembled a vast cross-section of artists that leverage design in their practices, and in doing so facilitated a number of new collaborative partnerships between individual practitioners and corporations. The abundance of objects and concepts in play left the “Footwork” space feeling slightly crowded, especially as a representation of a city whose prominent quality is a lack of density, but a surplus of design innovators is a good problem to have.

Ultimately, the most powerful forces within design are those that go unseen. The unavoidable takeaway from a week of presentations, research panels and formal and informal conversations, is that architects, designers and city planners spend a great deal of effort and energy in consideration of human activity, particularly in the context of population-dense places like cities. All systems that exist within human society are there by design, so it begs the important question: who designs these systems, and for whom? It is easy, in the course of a formal design education, to lose sight of your end user, and begin to design your population right along with your buildings, transportation systems and procedures. That’s why the work of engaging with and listening to the actual people who encounter design is the most crucial element of all. Akoaki suggests this, by bringing a large number of Detroiters to the table, but Knight arts grantee Cezanne Charles, founder of Creative Many, does this through her often invisible work of facilitation. Charles works so hard at building creative infrastructure in Detroit and beyond, that she risks becoming part of the wallpaper; to wit, she has built an organization that works to compensate for an entire missing piece of the puzzle, namely, the tools for individual successes to be scaled up to a higher level.

How perfect, then, that Charles chose to present a working coffee shop in her exhibition space. The ShiftSpace Café was designed by Detroit-based firm LAAVU and is stocked with hometown classics like Faygo pop and recipes from Sister Pie, as well as work by Detroit artists and designers, and reading materials from 826Michigan and others. It is the quintessential style of Creative Many and Charles herself to put Detroit creativity front and center. With its outdoor seating area just adjacent to the “Out of Site” courtyard, and an interior space hosting a full run of “Basic Universal” panel discussions, ShiftSpace provided a deeply necessary element of the biennial—a place for reflection and conversation—and remained one of the most active areas of the festival throughout its opening week. In true Creative Many style, the project also produced employment for 17 people.

There were so many heartening aspects of 2017 Biennale Internationale Design Saint-Étienne, and Detroit’s participation was a much-deserved opportunity to begin to connect with a worldwide community on the subject of reimagining cities. But exhibitions come and exhibitions go—the real work of redefining a city remains. As Detroit steps into a new age of development, it is perhaps timely to remember that design exists not only to reimagine and reshape society, but to serve and utilize what is already there.

The 2017 Biennale Internationale Design Saint-Étienne continues through April 9 at the Cité du Design in Saint-Étienne, France. Blogger Rosie Sharp attended by invitation, and travel expenses were covered through a grant written by Creative Many Michigan.

Rosie Sharp is a Detroit-based freelance writer and artist. Email her via [email protected] and learn more at sarahrosesharp.com.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·