Detroit looks to the future as a new UNESCO City of Design

In past years, the Detroit Design Festival has had a playful tone, with crowd-pleasing events like DLECTRICITY, that delight viewers with spectacles focused on the more ephemeral aspects of design. But this year, Detroit has a lot to celebrate, as it was announced in late 2015 as the first city in the United States to receive City of Design status from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)—making it part of an elite club of 47 other cities from 33 countries that are members of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network. The 2016 Detroit Design Festival programming embraced this new status, and brought together a powerhouse cohort of thought leadership to unpack ways that design and architecture may be used in pursuit of equity, adaptation and innovation—not just functionality or beauty.

“The thing about the City of Design distinction is transforming from disparate designers to a ‘city of design,’” said Garlin Gilchrist, a native Detroiter and director of innovation and emerging technology for the City of Detroit, speaking on a panel about sustainability. This and many other panel discussions were staged during the two-day Detroit City of Design Summit, organized by the Detroit Creative Corridor Center and Creative Many Michigan. Before a packed crowd at the Jam Handy building, moderators and panelists tackled issues that might typically be considered outside the range of architecture and design: gun violence, education, economic pluralism, and the history of hip-hop as allegorical feedback on the lived urban experience. The perspectives presented by the panelists opened the field of what constitutes design, and what interventions can be made through a process of redesign.

“The driver’s licensing process is a system that almost everyone interacts with, and nobody is very happy about,” said panelist Josh McManus of Rock Ventures, citing an example. “Everyone is clamoring to be the designer for a new building in Detroit, but no one is really interested in redesigning systems, like the DMV process.”

Knight Foundation has been a major supporter of the Detroit Design Festival over the years, and Detroit Program Director Katy Locker has a particular fondness and enthusiasm for the festival itself, as well as the potential it showcases.

“The Detroit Design Festival, including this year’s City of Design Summit, is about engaging the community in celebrating design and better understanding how design can be a part of our lives and our community’s success,” Locker said in an email interview. “When our city faces so many challenges, it is easy to be dismissive of the role of beauty and design.

“However, it is design that shapes our experience of a place, a thing, a moment. Design can make us safer. Design can make us healthier. Design can increase efficiency. And, of course, design can make us happier in a place or with a thing. One of the goals of the design conversation that will shape up over the 10 years of the UNESCO designation is to ensure that every Detroiter feels that the best design is for them. That great design is not exclusive to the elite of a community.”

That talent was on display everywhere you turned during the festival, supplementing serious think-tank activity and networking with many free events, such as Eastern Market After Dark; Light Up Livernois; a performance by Knight Arts Challenge winner Detroit Afrikan Funkestra; a presentation of work by the “Facing Change: Documenting Detroit” 2016 Spring Fellows; and a remarkable Penny Stamps Distinguished Speaker Series lecture on “performance architecture” by artist Alex Schweder.

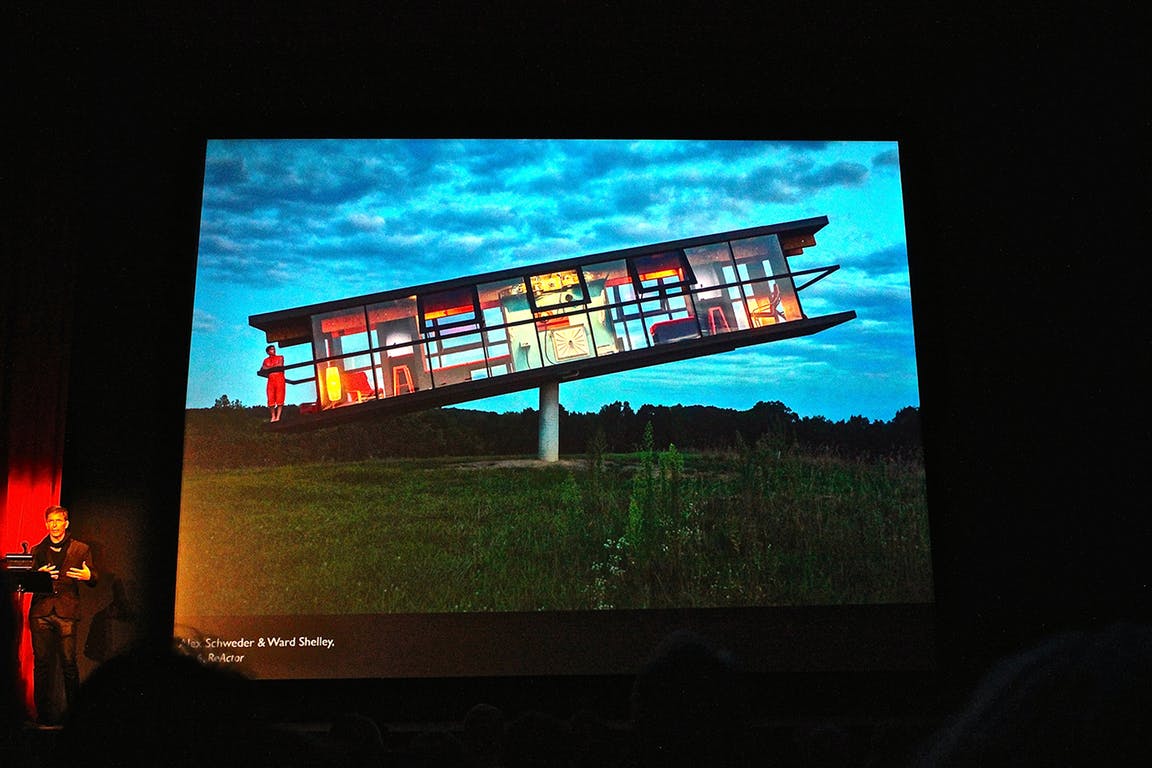

Schweder, who holds a Ph.D. in architecture from the University of Cambridge, gave an engaging talk at the Michigan Theater on Sept. 22, which presented an overview of his work as an artist. Over years of solo work and close collaboration with artist Ward Shelley, Schweder has developed the concept of performance architecture, which brings space and behavior—the underlying subtext of all architecture and design—into hyperfocus.

“Everyday actions are what architecture is made up of,” said Schweder, running slides and videos of his kinetic sculptures, such as “ReActor” (2016), a Modernist-looking house balanced on a giant cement pole, weighted such that the movements of occupants within the space shift the axis of the structure; or “Counterweight Roommate”(2011), where Schweder and Shelley lived for days in counterbalanced climbing rigs on a 30-foot tower equipped with basic living accommodations, the negotiation of which required total cooperation between the two artists.

Following the lecture, the audience was invited out to Liberty Plaza, where Schweder’s “TheHotel Rehearsal” was on view, alongside the 2016 POP-X pavilions, which include a crowdsourced poetry exercise by artist, educator, curator and “people person” Andrew Thompson; an installation by Flower House artist Lisa Waud; and a playful arrangement of plastic filament forms by Denver artist Jodi Stuart.

“The Hotel Rehearsal” is a mobile one-room inflatable “hotel”installed on a scissor-lift atop a van, and it was on the move: Schweder popped up at the evening’s Eastern Market After Dark to take interested passersby on a demonstration ride into the night sky. The popular recurring event was packed with Detroiters and visitors from all over the metro area, sampling food trucks, taking in fashion shows, and rubbing shoulders with some of the city’s scrappiest innovators in design and DIY culture.

The following evening, Friday, Sept. 23, came just as strong, with the adventurous venturing out to 5001 Grand River to see the second of three movements by installation artist Cristin Richard, “Metabolism: II.” Richard’s “MetabolismTrilogy” is meant to tap into three different sectors of the human being: the mind, the body and the spirit, using metabolism as a metaphor for the unique rate at which we as individuals process things. Part II examines the mind,specifically questioning our perception of our own reflection, which ledRichard, who often works with human subjects—to the incorporation of identical twins.

“For me, design is a 360-degree experience,” said Richard in an email interview. “In good design, all details are considered, from material usage to the user interface. I want the audience to feel something when they view my work, so I try to present it in an immersive way, tapping into their senses. Elements of sound, lighting and composition of space are integral. Fashion is another huge component, from the color and materials used to the techniques applied, down to the appropriate casting of the performers. But most important is the role of the research and study during the whole design process…this is what fuels the ability to make well-informed decisions.”

Richard’s installation was dimly lit and spooky, underscoring the sometimes otherworldly nature of twins—their aesthetic appeal and their somewhat insular ways of communicating with each other.

More along the beaten path, folks were flocking in droves to see the Detroit Afrikan Funkestra perform on Goodwin Street, just adjacent to the Oakland Street Community Garden. The garden is working closely with other North End organizations, such as O.N.E.Mile and the Detroit Afrikan Music Institute to lift up the thriving cultural scene that is reinvigorating a corridor that once was an entertainment hub in Detroit’s heyday.

“The thing about community engagement is realizing the community is already engaged, and there need to be better efforts to meet them where they’re at,” said Anya Sirota , a O.N.E. Mile organizer and principal at Akoaki architecture and design practice, during a panel at the Detroit Design Summit. “We are in a perfect position to judge our rights and wrongs, that other cities don’t get.”

The Funkestra performance, which took place on a futuristic stage with dramatic lighting, reached its peak around 8:30 p.m., leaving attendees enough time to catch the late showing of “Facing Change: Documenting Detroit,” an open-air slideshow on the east-facing wall of the Detroit Institute of Arts. The project—a subset of the national nonprofit Facing Change: Documenting America, which is dedicated to “exploring America and its critical issues”—was organized by co-founder Karah Shaffer and project co-director Alan Chin, and presented a short program by 21 Detroit-based photographers, each showcasing the city on their own terms.

As Locker says, “We are a city of such talent. Knight Foundation grantees play a critical role in highlighting this talent, sharing their stories, and ensuring that we leverage this talent as a collective force for the future of our city.”

During his lecture, Schweder shared a Winston Churchill quote that must hang on the wall of every student of architecture: “We make our buildings; thereafter, they make us.”Another Detroit Design Festival is in the books, but there is a sense of an ongoing effort to push our City of Design forward, in the direction of sustainability, in the direction of beauty, and in the direction of making the designs that will thereafter shape an innovative and inclusive future for Detroit.

-

Community Impact / Article

-

Community Impact / Article

-

Community Impact / Article

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·