First Amendment education surveys keep challenging us to try new things

We’ve done the largest string of studies about First Amendment education in America’s high schools, so what are we learning? This essay sketches out what our “Future of the First Amendment” surveys have been saying in 2004, 2006, 2007 and 2011. My bottom line: I had seen First Amendment education as a school issue; now, I think young people may be able to learn about the nation’s five fundamental freedoms outside the classroom as easily as they do inside. Maybe even easier.

Why did we start this research? Among adults, support for the First Amendment dropped frighteningly after the 9-11 terrorist attacks. In 2002, the First Amendment Center’s annual “State of the First Amendment” survey reported that 49 percent of Americans said they thought the First Amendment went too far in the rights it guarantees. Suddenly, America’s fundamental freedoms – long championed by the family that created Knight Foundation — seemed to be debatable. At the time, Knight Foundation’s journalism program had a large high school journalism initiative. So we called the survey group used by the First Amendment Center. We proposed a new version of their survey for America’s high school students, teachers and administrators.

The core of the Future of the First Amendment survey covered the basics. What do school folk and their students know about the amendment? Do they care about the 45 words that give Americans the right to say nearly all the other words? Each survey of our four surveys asked the core questions on freedom of religion, speech, the press, assembly and petition. Yet we also added new questions to help us probe why students believe the way they do.

2004: More than 100,000 students, teachers and administrators took the first Future of the First Amendment survey. It revealed a surprising lack of First Amendment understanding and appreciation in high schools. Three-fourths of the students said they either didn’t know much or care much about the First Amendment. This news made national headlines. Liberals and conservatives alike agreed something should be done.

A bright spot: Students who get First Amendment teaching in schools knew more about it than those without classroom instruction. In addition, student journalists, who get even more instruction, have an even larger understanding and appreciation of the amendment. A lot of people, including me, thought it was perfectly reasonable to believe increased teaching would help move students toward a better understanding of and appreciation for the First Amendment.

2005: Congress created the annual Constitution Day, requiring public schools to teach about the Constitution every year on Sept. 17, the anniversary of its 1787 signing.

We invested in teaching and resource programs, trying to put a First Amendment focus on the day. Grantees, including the Bill of Rights Institute and the Newspaper Association of America, distributed classroom materials. Channel One produced news stories and video lessons. We reached some 40,000 teachers. Our experiment hoped to show if the combination of news stories about our survey, the Constitution Day mandate and new teaching materials might increase First Amendment teaching and learning.

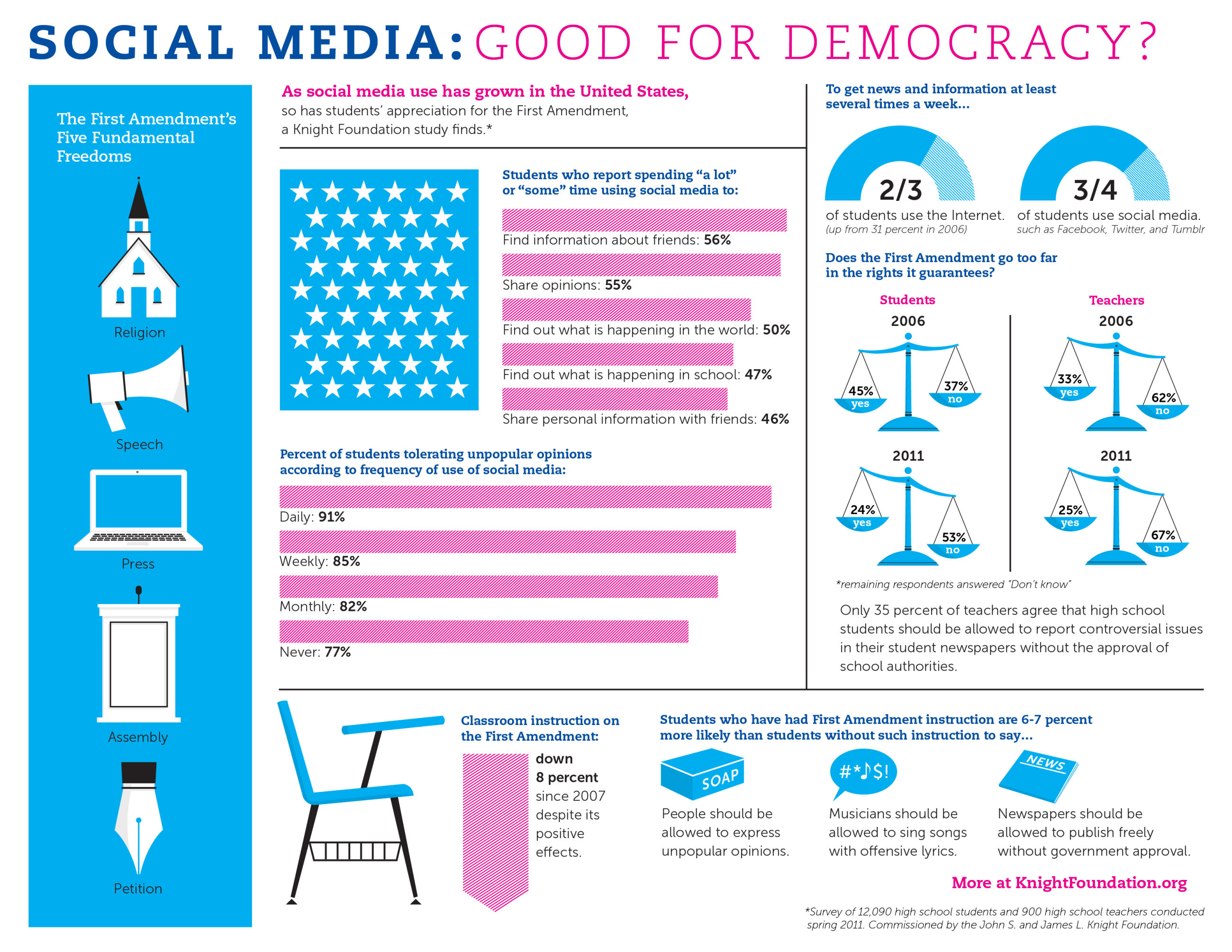

2006: Our second survey showed that teaching did increase significantly. Yet more students this time said the First Amendment goes too far — 45 percent, up from the first survey’s 35 percent. Apparently, many of the teachers who had not routinely taught the First Amendment simply weren’t very good at it. Where teachers had low opinions on freedom, they pulled the students down to their level. If you compare our teacher surveys to the First Amendment Center’s survey of adults, you see a general population less willing to say the First Amendment goes too far than high school teachers. On the other hand, when teachers strongly supported individual rights, it helped bring the students up.

The increase in teaching did not bring about an equal increase in learning. We started to question the idea of Constitution Day-style solutions. We wondered about connecting students to society at large. After all, the public seemed to like the First Amendment again. (The percentage believing it “goes too far” had fallen by 2006 from 49 percent to only 18 percent). Some scholars claimed (wrongly, it turned out) young people didn’t care about public life, so out-of-class lessons wouldn’t work. We, the team working on the research, realized we didn’t know enough. We wanted to know more about the power of Constitution Day, who influences young people, and if they consumed news.

2007: Our third survey showed that Constitution Day had not been as universal as we had hoped. Teaching was falling off again. But student support for the First Amendment increased. The survey also showed that parents — not teachers — have the greatest impact on the news choices of young people. Students were indeed connected. But they consumed news digitally more than traditionally. So the journalism team thought out-of-classroom projects might move First Amendment numbers.

By this time, many of our grants to increase teaching were running their course. We did continue to help education reformers like First Amendment Schools founder Sam Chaltain produce teaching materials and books through his Five Freedoms Project. But we worried about the difficulties of reforming the nation’s educational system. America’s largest foundation, the Gates Foundation, had published an assessment of its massive high school reform efforts detailing how complex, expensive and difficult education reform can be. We continued to wonder what, if anything, could happen outside the classroom that might help the First Amendment.

2011: Our fourth survey showed that high school students who used a lot of social media had greater First Amendment knowledge than the ones who didn’t. In the midst of a revolution in social and mobile media, for the first time since we started the surveys, student understanding and appreciation moved strongly in the right direction.

Again this time, teaching decreased while the learning numbers improved. How could there be less teaching but more learning? Perhaps using social media is like being on a school newspaper: You express yourself in public, so are more interested in the rules that govern public expression. Or perhaps it’s even more fundamental. Students strongly support freedom when it directly benefits them. They believe music lyrics and student newspapers should not be censored, for example, but don’t feel the same way about a traditional print newspaper. Since large majorities of students use social media, it’s “theirs” in the same way that music is theirs.

Many high school teachers, however, would dispute the idea that social media is a good thing: digital natives love it; teachers don’t. This seemed to offer another opportunity, so Knight partnered with the First Amendment Center and the Newseum to sponsor a college scholarship contest, “Free to Tweet,” as well as a teacher’s guide to social media.

What should the next Future of the First Amendment survey ask? Should we look more carefully at how teacher beliefs affect students? Try to figure out where teachers are getting some of their incorrect ideas about the First Amendment? Do their beliefs relate to their demographic, geographic, ideological, education or other factors? Are the teachers who are suspicious of digital media the same ones who don’t have strong First Amendment knowledge and beliefs? If teachers used social media more, would their First Amendment attitudes and knowledge improve?

Put in context, the glass seems half-full. First Amendment awareness and understanding among high school students appears to be increasing. High school journalism is plentiful, according to the survey by Mark Goodman, the Knight Chair in Scholastic Journalism at Kent State. And American Society of News Editors-led Sunshine Week seems to have helped rallied many groups to help people understand why Freedom of Information laws are important. (After 9-11, FOI laws were rolled back. That trend now seems to have stopped.)

Topics like greater public awareness of freedom and the success of high school journalism seem high-minded. But caring about them is not an academic exercise. Society is a complex social system, and it would be hard to prove in court that the work of any single foundation has changed the future. That said, this has been rewarding work. Projects like highschooljournalism.org had enough clear impact to draw strong funders, like Reynolds Foundation, to step in. Others, like the News Literacy Project, put together local funding packages. Some projects had strong matching funds from schools themselves and were continued by government, such as Prime Movers in Philadelphia.

We helped the Student Press Law Center raise an endowment to help push back against school administrators. (Too many still think media education means showing students who is boss and censoring high school publications.) Also, during the first decade of the new century, we partnered to create News University with the Poynter Institute. NewsU.org has 220,000 registered users and is such an effective educational tool Poynter made it central to the organization. The Newseum, the world’s only major museum of news, donated games to NewsU that teach the importance of news and the First Amendment to thousands of students every year.

We’re looking at continuing our Future of the First Amendment research with our collaborator, Dr. Kenneth Dautrich, a senior researcher at The Pert Group and professor at the University of Connecticut, has worked with us since the start. He co-authored a 2008 book, “The Future of the First Amendment,” about the first two surveys. I continue to wonder about out-of-classroom alternatives. Are social networks and games legitimate alternatives to traditional classroom work? In the 21st century, it seems harder to improve classroom teaching than it is to create a popular game or You Tube video. This too might be a good area to explore. We’ve done some early work on educational games, technology for innovation and digital media literacy, partly in connection with strengthening libraries in Knight Communities. The Knight Commission for the Information Needs of Communities has recommended that digital media literacy be incorporated at every grade level. (Digital media literacy certainly includes First Amendment education; it seems to include many forms of 21st century literacies — civic, news, media and digital literacies – all rolled into one.) Our grantees have called for universal digital literacy before standard setting groups, at teachers colleges and before testing institutions. Including the First Amendment in digital media literacy can offer another pathway for educators. In recent years, we have experimented with the new literacy idea at Stony Brook in New York and digital media literacy at Queens University in Charlotte. Perhaps these projects will demonstrate the democratic, educational and economic benefits of 21st century literacy.

A good portion of Knight Foundation’s work involves starting new things. This isn’t what many people think about when they think about government or foundation funding. Many do good work by doing what we would call charity: “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day.” Foundations call their work philanthropy: “Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.” And a few foundations do what you might call venture philanthropy: “Find a better way to fish, help people teach that, and see if you can end hunger.” It’s riskier. But when it works the rewards are much greater.

When you look at the successes of venture capital in the digital world, venture philanthropy doesn’t seem all that bold. Just think of how much digital media has changed since we did the first Future of the First Amendment survey: Facebook has become (if it were a nation) the third largest country in the world. Then Twitter came along, and it is now possible to imagine a day when the people of this planet will tweet more than all the birds. The younger generation, the digital natives of this social, mobile media world, seem to have a greater appreciation for the freedoms that make it all possible than the high school students who came before. To me, it’s a hopeful sign that these new digital tools can amplify the best in us.

By Eric Newton, senior adviser to the President at Knight Foundation

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·