Retro revelations and unsolved aeronautical mysteries at Napoleon

Two relatively infamous and unconnected events from the 1970s are being given a new treatment at Napoleon this month thanks to the exhibit “Holding Our Own” by artist H. John Thompson. A hijacker popularly known by the alias ‘D.B. Cooper’ disappeared without a trace along with $200,000 after rerouting a plane from Portland, Oregon to Seattle, Washington, and his audacious act has captured the imagination of speculators ever since it occurred in 1971. While the exact cause of the disaster is a mystery, the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald sunk on November 10, 1975 with all of its crew on board. Thompson takes these unrelated sets of circumstances and proceeds to weave them into a singular installation with focuses on carpentry, the style of the ’70s, lighting, woodworking and, of course, the vehicles themselves.

Upon entering the gallery space, the lighting is dim and the viewer is confronted by a grid of circular holes punched through a plethora of pegboard. On either side of the space, two large containers sit with rounded, rectangular portholes as if the exteriors of planes or boats, although the perforated top sections and kitschy wood paneling would seem to indicate something else entirely.

Carpentry is Thompson’s go-to medium, and he demonstrates his skill in a variety of ways. The wood panels are more a testament to his personal nostalgia for shag carpets and gaudily decorated basements, but the pegboards speak to hours spent taking down and hanging up tools from just such a spread. Instead of a place for hammers, Thompson utilizes the pocked up pressboard and faux-wood grain to craft capsules, one of which looks as much like something from “2001: A Space Odyssey” as a fixture inside a familiar workshop or studio.

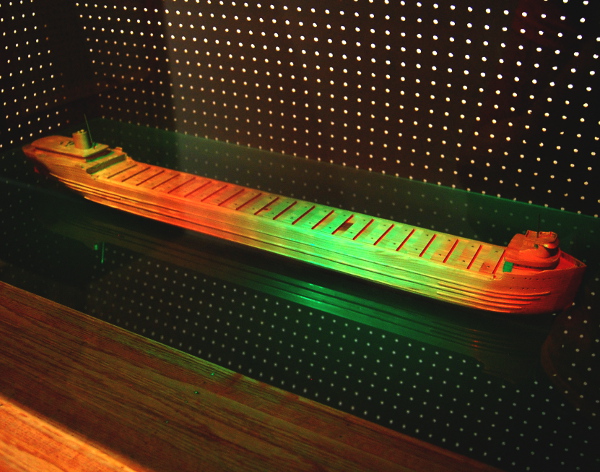

H. John Thompson’s model of the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald.

Having grown up across the street from a hobby shop, Thompson’s model-building skills are appropriately honed. When a visitor inevitably peers into the lone window on each container, they encounter a sterile little interior in which the holes of the pervasive pegboard become more like points of starlight than hangers for tools, quickly flipping the context from the commonplace to the celestial. Among these stars we find a model of the Edmund Fitzgerald and Boeing 727 in each display case, attentively carved from wood and lit with complementary green and red lights.

It would seem that Thompson questions the tendency for events like a hijacking and a shipwreck to become pop culture phenomena despite – or perhaps due to – their violent and disastrous implications. By placing these vehicles squarely between the ordinary and the cosmic, the insular and the infinite, the tales of both ill-fated voyages cling to their enticing mysteries as much as their terrible truths.

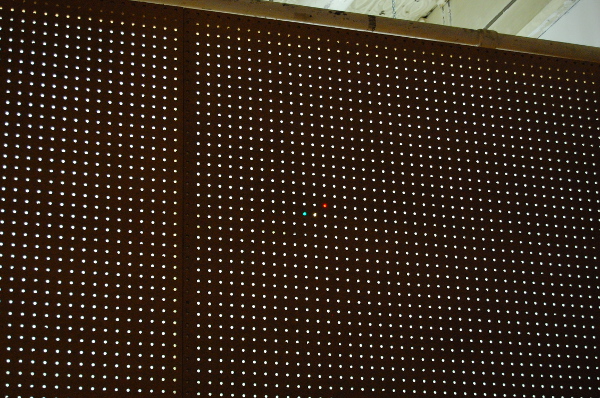

Two lights on the pegboard indicate the port and starboard sides of a distant vessel.

Withdrawing from the windows, the expanse of backlit holes at the far end of the gallery fully takes on the appearance of the night sky, albeit one full of eerily equidistant stars. Two tiny points of light near the top right corner shine in the red and green of port and starboard signals used by both airplanes and nautical craft. These signs of life in an otherwise unpopulated field prompt us wonder what exactly might be happening on the distant vessels, as well as where D.B. Cooper may have gone after he pocketed the cash and parachuted into the night…

Regardless of the things we don’t know, H. John Thompson does well to work from what he does. By utilizing carpentry, retro rooms, and realistic renderings of actual vehicles, the artist weaves a cohesive narrative out of two incomplete histories, while constructing a viewing space as much museum-quality as it is a throwback to cabins where smoking was permitted. “Holding Our Own” will be at Napoleon through October 30.

Napoleon is located on the second floor at 319 North 11th St., Philadelphia; napoleonnapoleon.com.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·