Imagination made useful: In conversation with Andrew Krieger

Detroit native Andrew Krieger was, until recently, a fulltime carpenter, but he returned to making art after a two-decade absence following a revelation of sorts — that his avoidance of art making was actually the symptom of something deeper, an evasion from some fearful element he’d been unwilling to confront. That sounds rather serious considering how truly fun and pleasurable much of Krieger’s work is, but that contradiction is actually the crux of his artwork.

Being an adult is serious business. Often we’re unable to even enjoy ourselves unless everything is on the line. This drives people to do insane things, like jump out of airplanes or mortgage their house to “invest” in a fleet of antique tractors. Or, in the case of artists, to gather friends and strangers in a gallery and invite them to stare at the idiosyncratic products of their obsession, an obsession that often carries with it the implied baggage of lost hours and lost wages and a loosening grip on the grimly dull requirements of practical adulthood. It is this kind of obsession that can make a grown man like Krieger quit his job and build an art workshop in his backyard. That Krieger’s workshop is essentially a fun factory doesn’t make it any less terrifying.

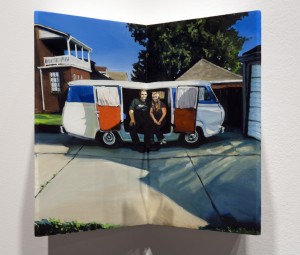

Since Krieger’s return to the art world, he’s been making an impressive variety of multidimensional work, often featuring small figures affixed to painted landscapes, but he’s also making action figures and electronic toys, such as a “King Kong Panic Playset.” He brings obvious carpentry talent to bear on his pieces, and along with that comes his desire for functionality, as well as a collaborative imperative for the viewer. Physical collaboration — in the sense of moving pieces around, as well as moving oneself around the pieces— and also creative, abstract collaboration, in the sense that much of his work creates the framework for an unfolding narrative, but doesn’t determine it, leaving the viewer to create their own story.

In “The Drink,” a series of dioramas display the same banal scene, that of a man sitting at a table, holding a cup and smoking a cigarette. But the perspective in each of the dioramas is drastically different — some are zoomed close in on the face, others are from the far side of the room — and the effect is that of an epic, tragic sweep. There is truly nothing more epic than the mundane, for the mundane is typically what’s happening just before the horror interrupts, and even sans horror it often masks a darker, inner tragedy. In “The Drink,” the subject could just be a guy taking a smoke break, but he could also be a relapsing alcoholic taking the first gulp of a destructive bender. It’s ultimately up to the viewer to decide.

It’s impossible to write about Krieger without mentioning his admiration for Howard Finster, the evangelist turned folk artist, who started making artwork after receiving a revelation: a mandate from God that he use art to spread the Gospels. Despite the overt, macabre message of Finster’s work — that you will enter hell unless you repent before your inevitable death—each piece radiates a childlike enthusiasm, the pure joy of an unbridled imagination, an imagination powerful enough to contemplate the void with enough grim seriousness to feel viscerally relieved to have discovered a way out.

In the great folk art tradition, for Krieger as well as for Finster, art must ultimately be functional, even when its main function is “just” to be enjoyed. It’s not made to be entombed in a museum beside a bewildering artist statement read by bewildered museumgoers. In fact, Krieger practically summed up his artistic philosophy by describing how he writes artist statements — as a way to explain the work to his grandmother. Which is not to say that artwork must appeal to real or metaphorical grandmothers — though I think that’s a fine place to start — but is more to say that artwork had better be at least pleasurable on its own, removed from the magic wand of the artist statement and the very serious pretensions of the art world — removed even, perhaps just momentarily, from the very serious pretensions of the practical world.

Current and upcoming shows include: “Love for Sale,” currently up at Work.Detroit: 3663 Woodward Ave., 313-593-0940, Work.Detroit. “Let’s talk about love, baby,” debuting Feb. 10 at MOCAD, a Knight Arts grantee: 313-832-6622, 4454 Woodward Ave. mocadetroit.org.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·