Moore departs on the exhibition without end

What would happen if an art exhibition didn’t come to a definitive end? Now, better yet, what would happen if a piece of art would continually change based on the interpretations of many minds across time and space? One could say that many artworks, once let loose in the public sphere, develop meanings and associations not necessarily intended by their creators; but for the ongoing “do it” project currently on display at Moore College of Art & Design, the march of instruction and intention is a perpetual motion machine for ideas that thrives on new artists and audiences.

Originally conceived by artists Christian Boltanski and Bertrand Lavier, and curator Hans Ulrich Obrist in Paris in 1993, the conversations about a nonstop exhibition eventually manifested themselves as “do it” — a series of openly interpreted written guidelines updated, adapted and proliferated worldwide. From the first 12 artists, the exhibition has expanded to hundreds more and appeared in more than 50 venues worldwide. Now Moore gives Philadelphia a chance to “do it.”

The show, which spans multiple galleries, is initially a bit daunting, with some 70 artists and a couple dozen distinct components. But after digging into a few of the descriptions and their accompanying work, the pieces slowly begin to fit. Placed near the entry, Yoko Ono’s “Wish Piece” is a simple place to start: a jar of tags and a small potted tree. Visitors may write a wish on these tags and then tie them to the tree until it is completely covered in wishes. Although a little trite, this physical process of writing down potentials and possibilities is a therapeutic starting place, if nothing else.

Ai Weiwei, “CCTV Spray.”

Others are considerably more technically elaborate, such as Ai Weiwei’s “CCTV Spray” which provides detailed plans for constructing a long, mechanical arm for wielding spray paint cans. Asking if we “feel uncomfortable, confused, disgusted, or even irate” because of a particular surveillance camera, the infamous Chinese troublemaker explains the process for spraying over these intrusive lenses. It would take a bold character to actually put this contraption to use, but its sentiment pervades far beyond its practicality.

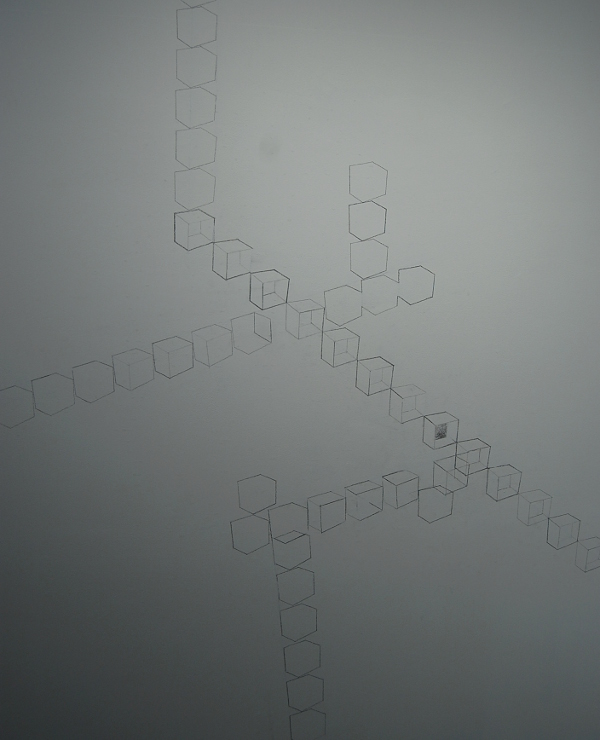

Fabrice Hybert, “To Scale” interpreted by Paul Hubbard.

Fabrice Hybert’s 1994 “To Scale” requires that a “General Practitioner born before 1961” draw a series of five-centimeter cubes at a random angle with different vanishing points for at least one and half hours. Interpreted by Paul Hubbard, this wall drawing explores new visions of relatively basic geometry, but the project itself, unlike many of its companions, sees itself with an eventual termination. Once no more General Practitioners with birth dates before 1961 are living, this exercise will cease and become an impossible work of art.

Erik van Lieshout, “Instruction” interpreted by Beverly Brooks, Aubrey Bugge and Autumn Mapp.

Taking a brand name approach by hailing Nike’s similar-sounding slogan, Erik van Lieshout requests that participants ‘Just do it’ and cut their shoes into Nike Air. These loose rules allow for some degree of openness as Beverly Brooks, Aubrey Bugge and Autumn Mapp slice and dice their athletic shoes into glorified sandals while leaving the swoosh logo in tact. By leaving the name recognition in place, we are able to perceive the brand and the material of the garment independently, breaking fashion down into its component parts.

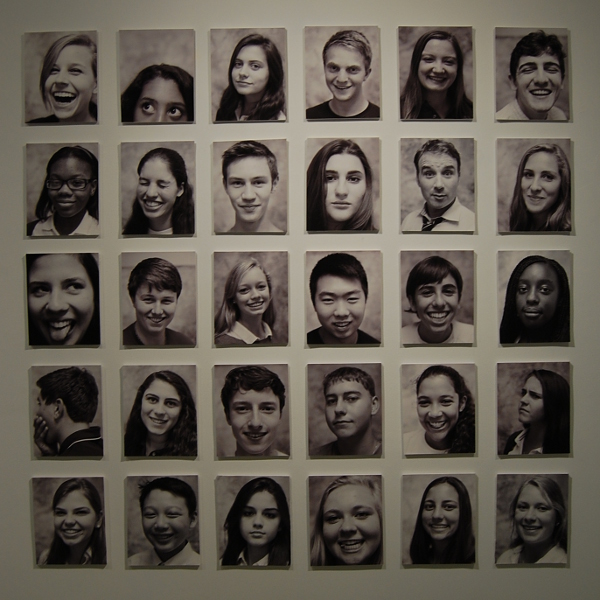

Christian Boltanski, “Les Écoliers (The Schoolchildren)” interpreted by Michael Leslie.

In “Les Écoliers (The Schoolchildren)” by Christian Boltanski, the artist provides detailed plans for photographing a class of school pupils. Like the awkwardness of photo day with a twist, we find the students acting like themselves in front of a professional camera instead of contorting into unnatural poses. Michael Leslie interpreted this with a local theater class, allowing for a wide range of individuals and expressions. Upon completion of the exhibit at large, the photos are distributed to the students and their families.

Aníbal López, “For Rent” interpreted by Gibbs Connors.

Aníbal López includes one of the most intriguing ideas with “For Rent” in which the title’s two word phrase is to be printed on a white background in black Arial font by a professional sign painter. Living up to its claim, the painting interpreted by Gibbs Connors is available to rent for $20 per day and used in any way the renter wishes – including alteration. Each time it is rented, a non-digital photograph is to be taken (presumably for documentation purposes), and at the end of the exhibition, it is to be destroyed. In this way, the sign will live out numerous lives with slight variations, and remain only in images, not as an object. Indicative of many of the works in “do it,” this represents a sort of open-source artwork with a paper trail and no sense of finality.

By spending time with the projects at Moore, we may see art as a give-and-take process of imagination, interpretation and appropriation, and aside from the objects that exist as byproducts of this exchange, we are able to more clearly see the true face of the dialogue that constantly bubbles below the surface. See this iteration of “do it” at Moore through December 6.

Moore College of Art & Design is located at 20th Street and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway; [email protected]; moore.edu.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·