Poetry in motion: An O, Miami project uses Google search to shift perceptions

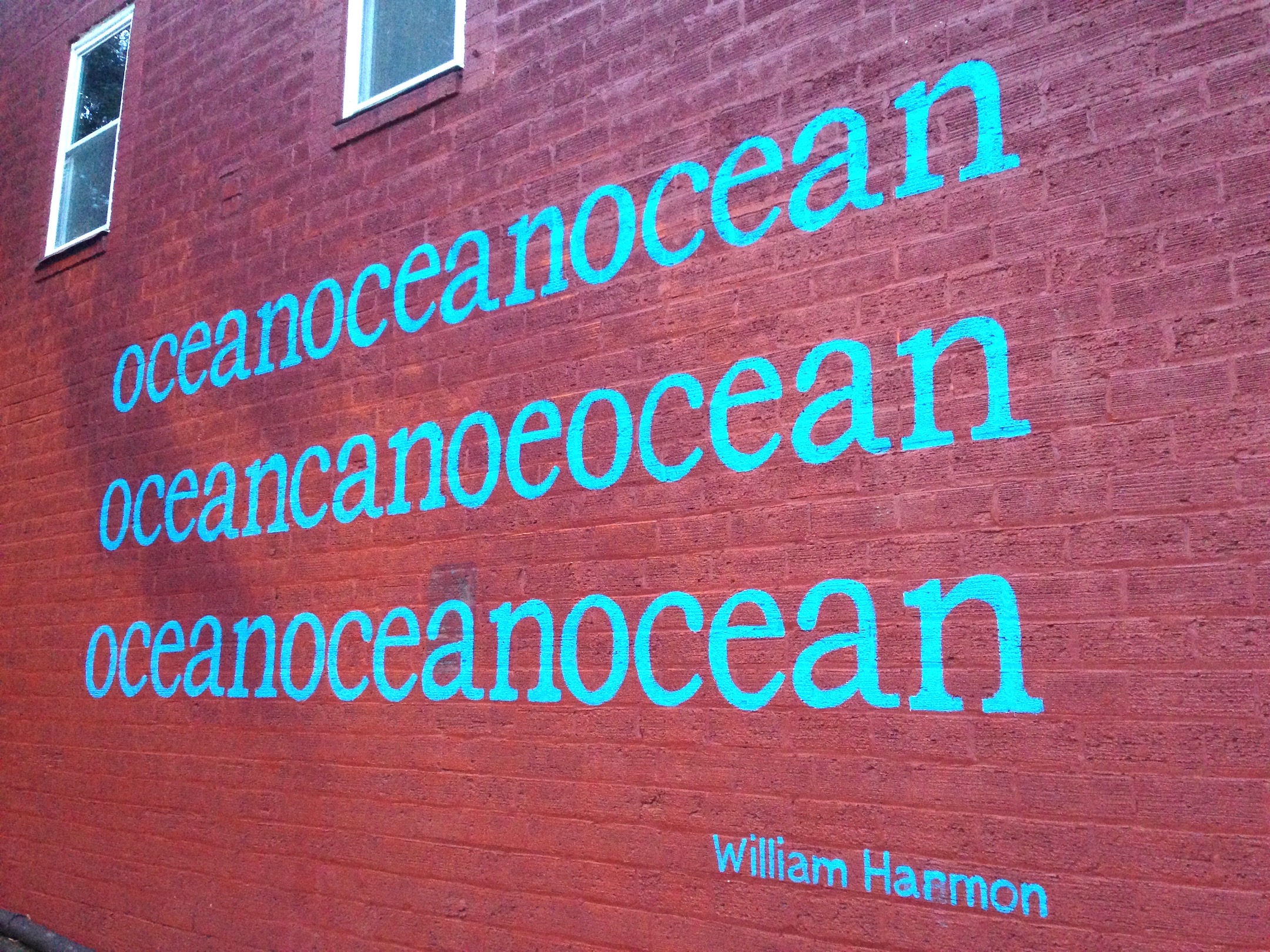

Over the years O, Miami, the annual, monthlong poetry festival in South Florida, has used billboards and bus stops, benches and pieces of paper sown into garments in thrift stores, to bring poetry to the residents.

This year, O, Miami is putting poetry into a Google search.

Through repeated searches using six one-line poems that start with the words “Miami inmates,” “View-Through” aims to tweak the results produced by the predictive algorithms that govern Google search.

The project is a collaboration between 110 inmates in Florida correctional institutions in Miami-Dade County, O, Miami, the nonprofit Exchange for Change and visual artist Julia Weist. The results offer beauty as they also humanize our perception of the inmates who created the poems and subtly question some of the associations we unthinkingly accept, every day, sometimes many times a day, in our language.

“One way of disregarding or not paying attention to a certain group of people is the language we use about them,” said P. Scott Cunningham, founder and director of O, Miami, which receives support from Knight Foundation. “If you can change the language around a person or a group of people, you can change the way people think about them and how they feel about them. And, also, you can see how something that is an assumption, by being put in certain ways in the digital realm, get reinforced as reality. This is an effort to get people to pay attention. To me, that’s the goal of the project.”

Weist, meanwhile, noted that until recently, when typing “Miami inmates” as a search, the first suggestion was “attack,” and even though violent crime in Miami-Dade has decreased in the past five years, according to the Google trends database, the correlation between assault and inmate increased almost 4,000 percent. (Search suggestions are tailored to location and change over time.)

The participating inmates, all students in the Exchange for Change writing program, were asked “Why did you participate in this project and/or why is it important to you and in general?” Roderick Richardson responded, “It lets me know that my thoughts are going beyond the gates that entrap me physically but not mentally. It gives me the opportunity to show the world that I am more than just a number or another statistic.” Fellow inmate David Hackett wrote, “Through this project I can be part of a reform in the way people think and see people in prison.” And Ben Ice wrote, “Many that live a normal life could easily be here, and the conditions we live in aren’t acceptable. We love, feel angst, loneliness, depression and joy. I am not an animal. I am a human, intelligent and worthy. I have made mistakes and have and am paying my penance for them.”

Cunningham said the idea of an online project for O, Miami first came up years ago, “but we really never found the right project.” Then he read a New Yorker story about Weist and an intriguing conceptual piece using “parbunkells,” a 17th century word that was all but missing from the web. Weist set up a page with the word, then put it on a 50-foot-wide billboard for 38 days on Queens Boulevard in New York; people Googled “parbunkells” and it entered the search engine world.

“It was a really smart project, and it was about language and the interaction between the physical and the digital world, and I thought it would be perfect for O, Miami,” said Cunningham. “We had been doing these poetry workshops in the detention centers for the past couple of years in collaboration with Exchange for Change and [Weist] really liked the idea of using their work. She came to Miami, visited the detention centers, met with the students [in the Exchange program] and with Kathy Klarreich, the director of Exchange for Change. They do all kinds of workshops in the prisons. We solicited poems specifically for the project. 110 [Exchange for Change] students/inmates participated and 650 poems were submitted, and then we narrowed it down to 5 or 6.”

The six poems are:

Miami inmates are sunbathing underwater

Miami inmates are what becomes of the chicken before I fry it up

Miami inmates are a device used to tell time

Miami inmates are light of the world, bone of men

Miami inmates are items of furniture for frightened people to lie down and rest upon

Miami inmates are believing in the unseen

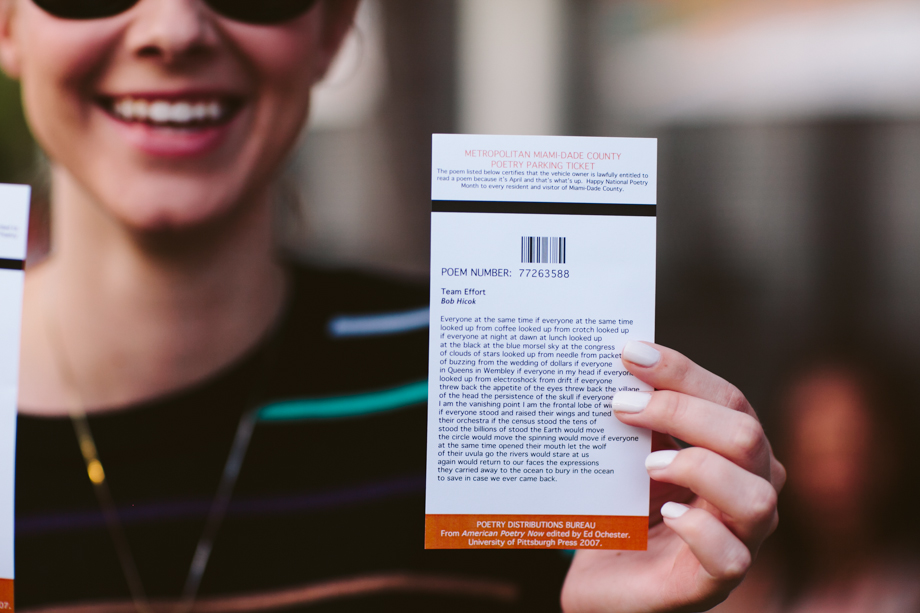

During the festival in April, one of the components of the project will be advertising around Miami-Dade County, on bus shelters, bench ads and small billboards, encouraging people who would not normally use this search to do it so they can see the poems. There will also be newspaper ads asking people to “Stop Googling ‘Miami inmates’”—the idea being that a great way of getting people to do something online is to pique their curiosity or to tell them not to do it.

Cunningham and Weist aren’t certain how many searches are needed to induce the Google search engine to produce the desired suggestion. “We got about 500 searches last weekend and one of the poems popped up on the search terms,” said Cunningham. “But what I’m learning about it as we do it is that you can create the effect for a little while but then it will reset itself or there might be other things that become more prominent and it will change again. It’s a temporary intervention.”

And, no, O, Miami organizers didn’t discuss the project with Google. “Obviously, this is a sensitive topic for them because the core of their business is search,” said Cunningham. “But the more I talk about it, the more I think that they would be in favor of it because it’s not that we’re trying to cheat the system. We’re not. We are trying to make something important enough to enough people that it becomes searchable. It’s not Google that we’re trying to manipulate; it’s the world.”

Fernando González is a Miami-based arts and culture writer. He can be reached via email at [email protected]

-

Arts / Article

-

Arts / Article

-

Arts / Report

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·