“Without Sanctuary” examines a horrific chapter in our history

Lynchings are not a part of our past many of us wish to dwell on or even acknowledge. Instead public memory wishes to suppress this past atrocity. Not only is the abstraction disturbing to our concepts of law and justice, but when faced with the factual details, we feel nauseous and brutalized. The memory of this racialized, violent spectacle — for that is what lynching became during the late 1800s — must be preserved, and this is precisely what the Levine Museum of the New South (a Knight Arts grantee) is doing through the exhibition, “Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America.” “Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America” Levine Museum of the New South. Front right: “Bound in Yes” by John Love.

As Levine President Emily Zimmern said, “to recognize the humanity of those who were executed, to acknowledge that these atrocities took place, and to promote cross-cultural discussion that can bring healing and vigilance against future acts of bigotry and violence,” we must remember. Importantly, the Levine Museum recognizes the necessity of exploring and preserving horrific chapters of our nation’s history along with the flattering ones.

“Without Sanctuary” explores lynching in the United States and particularly the South through the disturbing photographs, postcards and memorabilia from these horrific events. The artifacts were gathered by James Allen, an antiques collector, who happened across a lynching postcard and recognized the potential of these artifacts to help society remember and discuss the brutal violence of these killings. The Levine will display approximately 70 images from Allen’s collection, now part of the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, through December 31.

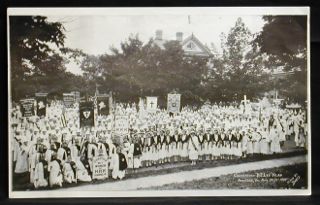

R.E. Lee Klan Convention, Roanoke, VA 1931. Photo by Davis. Courtesy of Levine Museum of the New South

Importantly, the exhibition provides much needed context for these graphic images, examining the rise of lynching in America and its transformation into a community spectacle targeted at black suppression. “Without Sanctuary” deposes several key myths held about lynching, including that it only happened to men, only in the South, and that the victim had definitely committed a crime. “Without Sanctuary” shows lynchings were not confined to a period, place or race, although 70 percent of the 4,700 people lynched between 1882-1968 were African Americans. Lynching, in fact, happened right here in and around Charlotte. Several panels in the exhibition discuss documented lynchings in the Carolinas.

Sign courtesy of Levine Museum of the New South.

Thought-provoking questions involve the visitor at each stage of the exhibition, allowing visitors to reflect on the images and information and offering a chance to respond. One of the most evocative questions asks “Can you imagine yourself in the picture? As a bystander, a victim, member of the mob, photographer or someone who chose to stay at home?” This question is troubling to think about, and yet it guides the viewer into connections with contemporary acts of bigotry and violence. For as one contemplates where they would have been in the past, their present position in regards to racism and hate crimes comes into play.

Another significant interactive part of the exhibition is artist John Love’s installation “Bound in Yes.” The piece is simple yet stimulating. At a basic level, it asks viewers to take all that they have just seen and learned and respond to it positively by writing down an affirmation on a card and tying it to a rocking chair. These positive affirmations offer a healthy way for visitors to respond when confronted with the horror of this negative chapter in our history. “Bound in Yes” sums up the entire exhibition and its goals by asking visitors to neither forget nor ignore this part of history but move beyond it to shape a future where lynching is not possible.

Levine Museum of the New South: 200 E. 7th St., Charlotte; 704-333-1887; www.museumofthenewsouth.org. Open Monday-Saturday, 10 a.m.-5 p.m. and Sunday, 12-5 p.m.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·