Two Detroit writers shoot from the hip with emotion-packed book launches

Above: Desiree Cooper’s grandson Jax joins her onstage during her reading. Photos by Rosie Sharp.

Detroit’s literary scene is booming. Last week, two local authors held book launches for work that touches deeply on some of the most difficult and most real parts of being human, being black and being female: Desiree Cooper debuted a collection of flash fiction, “Know the Mother,” while Casey Rocheteau–the inaugural awardee of the Write-A-House program, which is funded in part by Knight Arts–unveiled her new poetry collection, “The Dozen.”

A 2015 Kresge Literary Fellow, Cooper hosted the launch event and reading for “Know The Mother” in the Scarab Club’s main gallery on March 15. Organizers should have cautioned audience members to come armed with tissues, as Cooper’s work is powerful and extremely real.

“These stories aren’t autobiographical,” Cooper said between reading pieces. “But they are all true.”

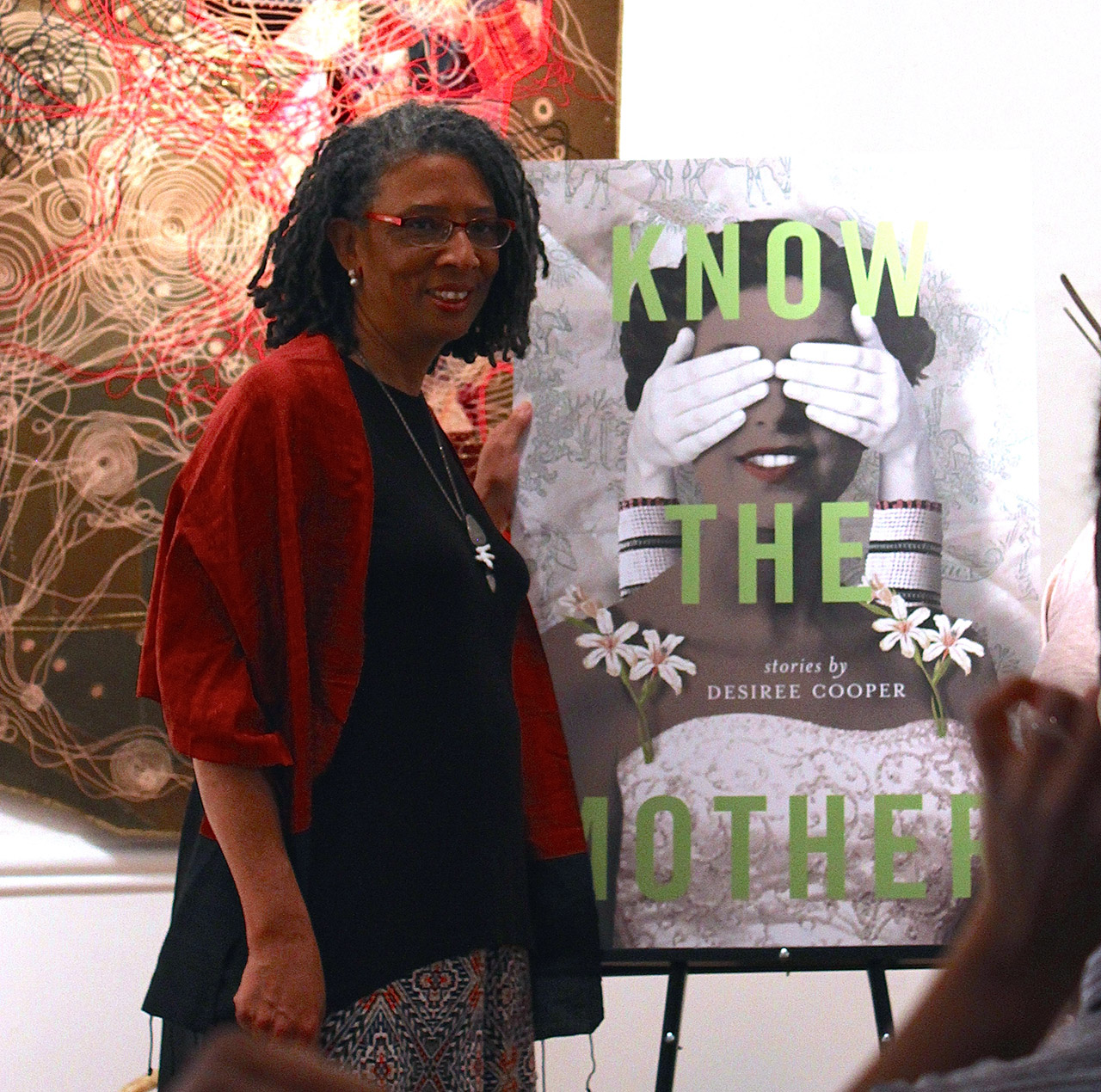

Desiree Cooper poses with her book cover.

A lawyer, longtime columnist for the Detroit Free Press and Pulitzer Prize-nominated journalist, Cooper found that when she finally had time to focus on her fiction writing–a passion she’d held since the age of 4–she could not sustain interest or tension across long-form writing. Fortunately for her and her readers, she discovered the genre of flash fiction, which packs narratives into short-short stories. Rather than fight all those years of professional conditioning, Cooper simply turned the reflex toward fiction.

“Flash fictions can be up to 1,000 words,” Cooper explained to the audience. “But my column was 750 words, and I just kept flexing that muscle.”

The results are breathtaking. Long-form fiction gives us all the time in the world to know characters, to embrace them, before we lose them. Cooper’s stories jump off directly in the midst of secret, highly fraught emotions, capturing snapshots that radiate love, intimacy, fear and loss. “Know the Mother” is a series of 30 gut-punches—brief, ruthlessly effective and hitting the reader directly in the vitals.

Cooper’s potent emotional realities are often tied up in historical factoids and research, as with “The Witching Hour,” which opens both the book and the reading. Introducing the piece, Cooper describes the ages-old characterization of the witching hour—from 3-3:15 in the morning—as being the unholiest time, being diametrically opposed to the time of the crucifixion (thought to have taken place at 3 p.m.). Another, “Second Sleep,” references the Victorian custom during long nights of winter to break from sleeping for a midnight meal before returning to bed. Cooper’s protagonist in this story wakes to a spirit gathering of her closest lost loved ones. Like a visit from a ghost, the story packs an incredible dose of longing and aching loss, before quickly fading away.

“I think we get very wrapped up in telling ourselves perfect fairy tales,” said Cooper, in response to an audience question about her views on gender oppression—a topic that she explores with great eloquence in her work, returning again and again to the fundamental unknowability of these women we call mothers. “As a result, we end up hating ourselves. Where is the place to talk about the struggles, the challenges of motherhood or marriage? Women talk about this all the time. Why aren’t we writing about it?”

Cooper would be heartened, I think, had she attended launch of Rocheteau’s “The Dozen” the following night at the N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Arts, a Knight Arts grantee.

Casey Rocheteau reading from “The Dozen” against the dramatic backdrop of a painting by Saffell Gardner.

Rocheteau shared the stage with openers Corina Fadel, Siaara Freeman and Sherina Rodriguez Sharpe–all four of whom spoke incredible truth to harsh realities. Fadel’s lyrical musing on the murky combinations of family recipes and family abuse set the stage for an evening of keeping it real, followed by Freeman’s intense staccato-spit delivery of two poems from a collection dealing with black cartoon characters. The opening line-up was closed out with Sharpe’s offering, “Bridge,” a ‘definition’ poem that was the culmination of her search for her own poetic voice, after spending a long time working in the voices of others. “My father’s voice is in song lyrics,” she said, “and my mother’s voice is in recipes. My brother’s is in video games, because he loved to play them. After working with them for so long, I had no idea anymore what my voice was. But I discovered it is in dictionary definitions. I like to define things, and I don’t like having them defined for me.”

All this paved the way for Rocheteau, who came riding through as defiant and triumphant as the girl on the cover of her new poetry collection (illustration by Vanessa Reynolds). The cover features the character of Topsy, from “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” riding Topsy the elephant—to whom a suite of poems that bracket the collection are dedicated—away from a burning circus, “and all the clowns inside it.” As anyone familiar with Rocheteau has come to expect from her, she threw down a firestorm of eloquent rage, with poems calling names that haunt America’s consciousness: Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, the Lower Ninth Ward and others. Shame on me for failing to learn a lesson and forgetting tissues again.

You would do yourself a favor to pick up these new publications by some of Detroit’s most earnest writers. Pick up some Kleenex, while you’re at it.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·