Hippie Modernism at Cranbrook Art Museum highlights a struggle for utopia that remains relevant

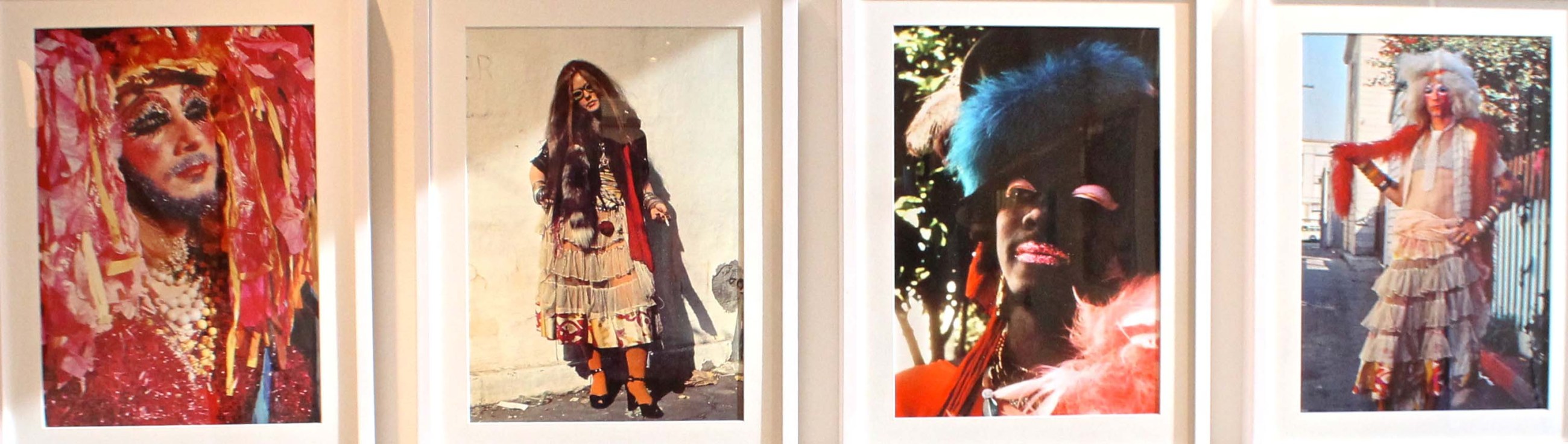

Above: Gregory Pickup, stills from “Pickup’s Tricks” (1973). Photos by Rosie Sharp.

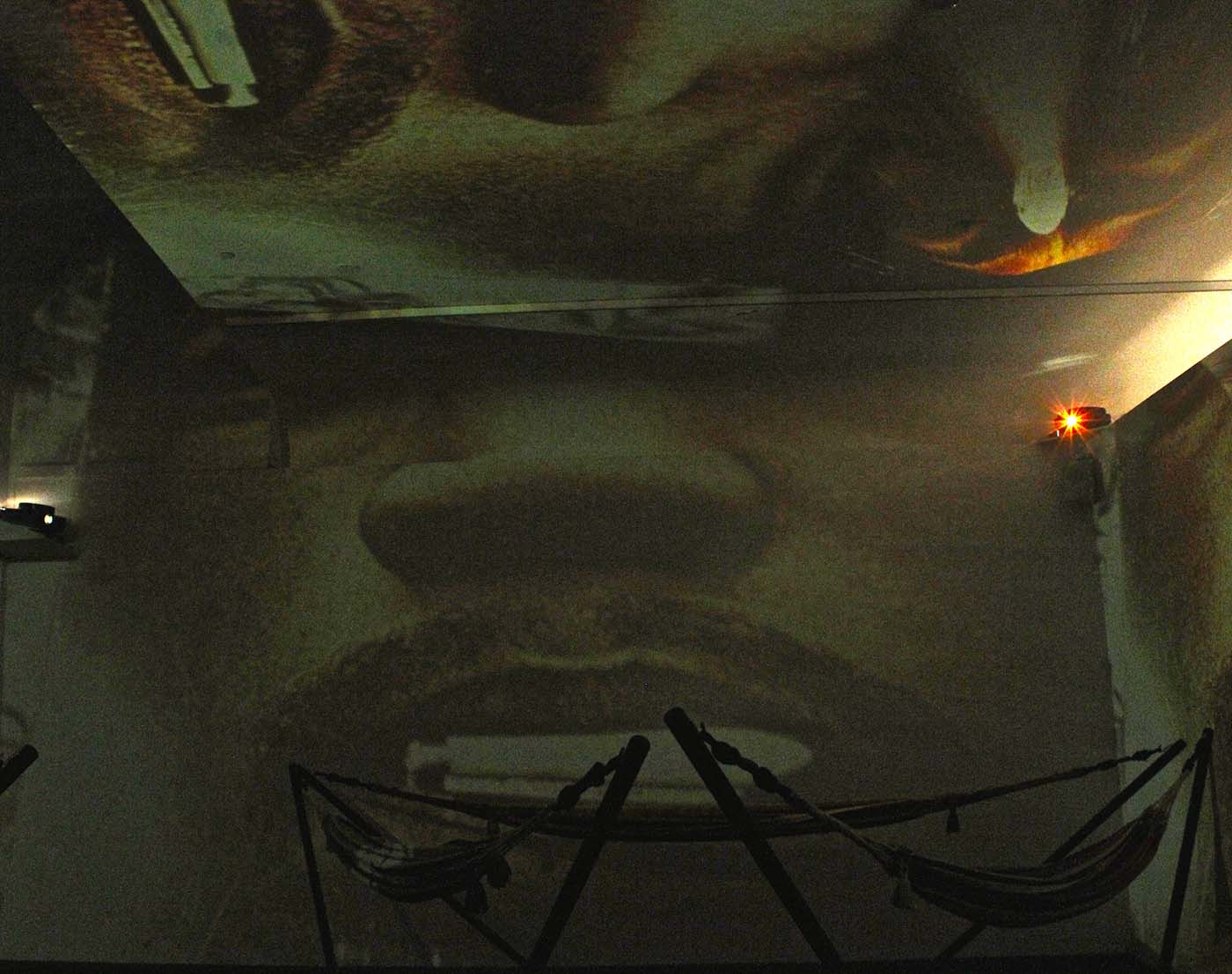

If you lack the tolerance for Hollywood blockbusters, here’s a tip to beat the heat in Detroit this summer: Take in “CC5 Hendrixwar/Cosmococa Programa-in-Progress,” the full-gallery installation of a work by Hélio Oiticica and Neville D’Almeida.

Tucked away in the furthest reaches of “Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia” at Cranbrook Art Museum, the installation comes complete with gratifying tunes, soothing visual projections and hammocks. Along the way, you’ll have a chance to soak in an astonishing array of materials assembled initially for the Walker Art Center by Andrew Blauvelt; fortunately for Metro Detroiters, the exhibition seems to have followed on his heels as he assumed the mantle of director at Cranbrook Art Museum. The full-floor exhibition is a heady chaser to the massive survey of old and newly-commissioned works by Nick Cave, which was funded by a 2014 Knight Arts Challenge grant, and will be followed by a Knight Arts-funded Detroit tour of Hank Willis Thomas’ “The Truth Booth,” opening in November of this year.

Hélio Oiticica and Neville D’Almeida, “CC5 Hendrixwar/Cosmococa Programa-in-Progress.”

Hippie culture has mainstream associations with the San Francisco Bay Area or upstate New York, but “Hippie Modernism” recasts this period of intensive culture shift from the mid-1960s through the early ’70s in a global light, and shows how hippie aesthetics and values informed and absorbed global trends in design, politics and environmentalism—not just the sex, drugs and rock-and-roll that are the movement’s trademarks. “The period under consideration is a historical transition from one epoch to another: from an industrial to a postindustrial society and from a culture of an ossified high modernism to a nascent postmodernism,” writes Blauvelt in his introductory catalogue essay, which prefaces a weighty tome assembled by the Walker Art Center—a must-have for anyone wishing to absorb the full measure of this incredibly dense exhibition.

Loosely organized into the categories Turn On, Tune In and Drop Out (which collectively reference a movement-catalyzing quote by Timothy Leary), “Hippie Modernism” collects works of the period that examine expansion of individual consciousness, increased social awareness and a “diverse range of refusals,” respectively. These manifest variously as straightforward artworks, such as paintings by Isaac Abrams or conceptual sculpture works by Viennese design collective Haus-Rucker-Co; audio/video rooms featuring sensory mash-ups of drumbeats and digitized geometrics, such as “Allures” by Jordan Belson or experimental films like Bruce Conner’s “Breakaway”; and interactive works such as the mind-bending “Ultimate Painting” by Clark Richert, Richard Kallweit, Gene Bernofsky, JoAnn Bernofsky and Charles DiJulio. Additionally, each room is replete with visual matter, including psychedelic posters, various propaganda and informational materials, art collective chronicles and independent publications, such as Stewart Brand’s extremely influential “Whole Earth Catalog.” There are some local points of interest, as well–namely “The Cranbrook Design Trip” by Katherine McCoy and Edward Fella, which chronicles a 2,284-mile cross-country road trip undertaken in the fall of 1973 by Cranbrook students and faculty.

Evelyn Roth, “Family Sweater.”

Within the gallery devoted to refusals are seemingly benign objects, such as Evelyn Roth’s “Family Sweater” and “Environment for Reading Recycled From 110 Sweaters,” which are created from salvaged thrift-store sweaters and underscore her interest in concepts of recycling, but also domestic interventions in space. Even the simplest components of “Hippie Modernism” merit deeper reflection, perhaps within the Relaxation Cube from “Nomadic Furniture 1” by Victor Papernack and James Hennessey–a modular relaxation space equipped with floor cushions, a comfortingly retrograde television screening “East Coast, West Coast” by Nancy Holt and Robert Smithson, and a slide projector running imagery.

Ken Isaacs, “The Knowledge Box.”

All of this makes for an extremely dense exhibition, so be sure to leave plenty of time to take in all the materials, which provide a perfect jumping-off point for those seeking an introduction to or a more nuanced understanding of hippie culture. At a moment where we are confronted by fractious social movements and turbulent politics domestically and abroad, “Hippie Modernism” is perhaps a timely mirroring device for our current-day issues. It is a richly layered exhibition, artfully balancing food for thought with space for decompression. The whole exhibit can be effectively mimicked by Ken Isaacs’ “The Knowledge Box,” which subjects those willing to enter the inner chamber to a 360-degree show administered by 24 slide projectors at right angles, firing images from popular magazines from the 1950s and 1960s onto every available surface for an intensive three minutes. It is impossible to leave “The Knowledge Box”–or “Hippie Modernism” writ large–without feeling a bit overwhelmed by information. All the better, then, that we have a long, hot summer to revisit and reconsider what themes and lessons this show has to impart.

“Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia” runs through October 9 at Cranbrook Art Museum.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·