How can democracy thrive in the digital age?

In the wake of revelations that political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica improperly used Facebook data to influence the 2016 election, scrutiny of the social media giant continues. In the past month, Facebook has been hit with information requests from an alphabet soup of federal agencies — the Department of Justice (DOJ), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

But the issue is about more than Facebook and has implications beyond breaches and rights to privacy. We’re experiencing a sea change in our relationship to a relatively small set of companies. Just a few brands — Facebook, Google, Apple and Amazon — occupy many of our waking hours.

They are where most of us entertain ourselves. They are where we meet and converse with friends. They are how many of us shop. They are where political debate is happening. The reality is that it’s harder and harder to transact our social, commercial and political lives in any kind of “offline” fashion.

This matters for our democracy. The way we inform ourselves about public affairs has moved from the morning paper and evening news to a constant stream of mobile alerts. Political debates have shifted from in-person affairs to pseudonymous shouting matches. Our expectations for government and other institutions have shifted to an internet standard — any service that doesn’t deliver with Amazon Prime or Netflix levels of instantaneity is frustrating and obsolete.

And at the center of all this are a handful of technology companies that have spearheaded the disruption and now wield substantial power in the marketplace and in our lives.

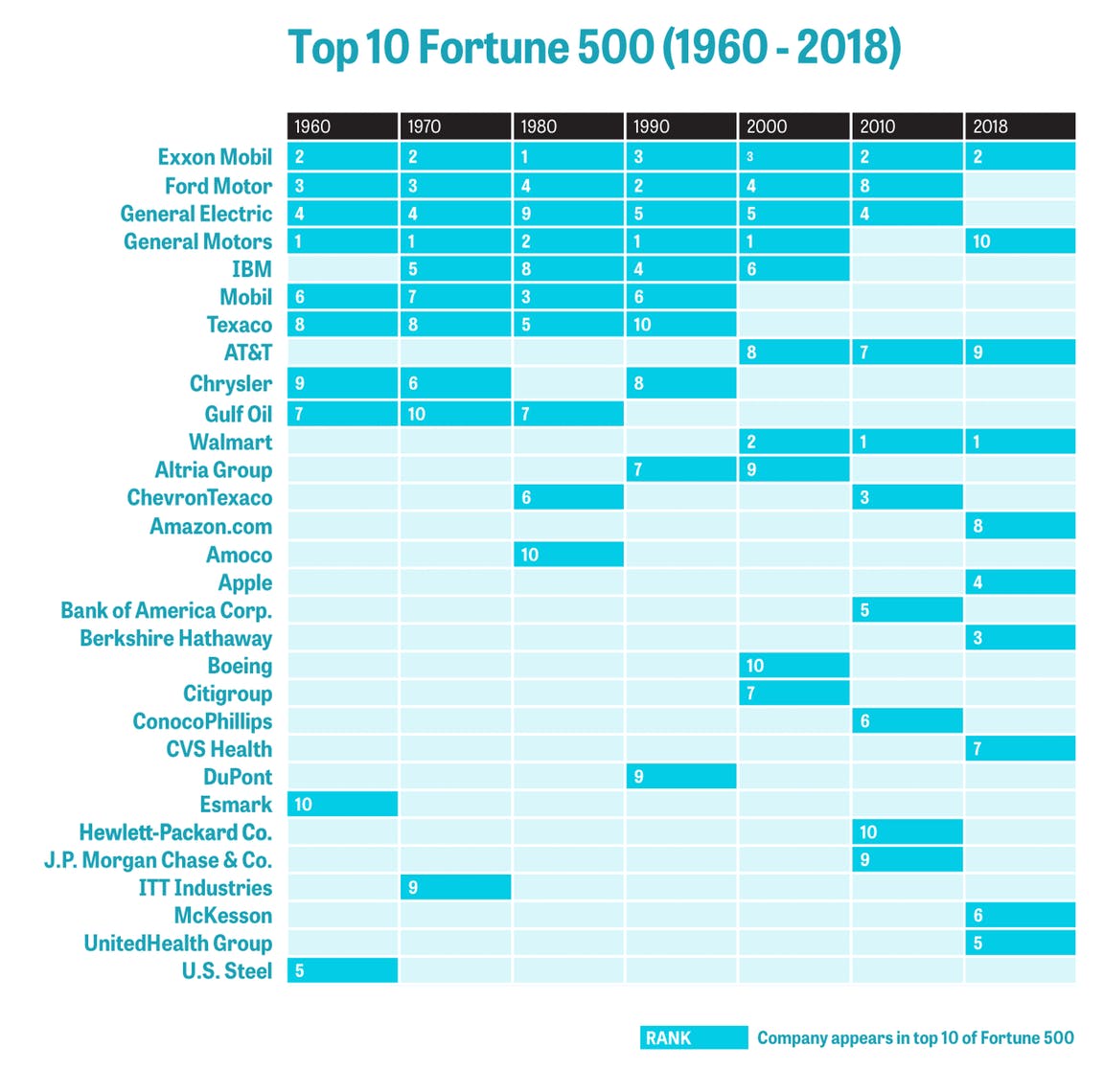

It’s worth reflecting on just how rapid this transition has been. The chart below shows the top 10 of the Fortune 500 — which measures revenues — at each decade from 1960 to today. The stability is remarkable. From 1960 to 1990, the same handful of companies simply change order. Apple, the company with the highest market capitalization in the world, wasn’t even in the Fortune 500 top 10 as recently as 2010.

We can therefore interpret the many federal requests issued to Facebook not just as a worry that something may be amiss in their business practices. It is a sign that our society and its institutions are reeling and desperately trying to catch up to a fundamental shift in how we live our lives. We don’t have a single expert agency in charge of the rules of the road online. We don’t have an established body of law to help make the hard calls. We don’t even have anything approaching consensus in society about what it means for the digital world to be safe and safely democratic.

As more recent controversies confirm, it’s clear we’re off the map in some sense. Just over a week ago, Facebook attracted attention for indicating to a room of journalists they would not ban the site Infowars, despite a clear track record of misinformation and conspiracy theories. And in a span of days, CEO Mark Zuckerberg was caught in an uncomfortable discussion with journalist Kara Swisher about why he would not ban Holocaust denialists from the social network.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we figured out that when it comes to food or household products, consumers can expect truth in advertising and basic physical safety standards to be met. In the middle of last century, we decided that we liked big and fast cars — but not without seatbelts and airbags. In each of these cases, we developed a set of norms and codified them in laws, corporate practices and consumer behaviors.

None of that exists in the online world. And so, even when something goes manifestly wrong, it sends four different federal agencies scrambling.

And this new digital challenge includes news. In a survey of over 19,000 U.S. adults that we commissioned with Gallup, 58 percent said the abundance of information in today’s environment has left them feeling less informed. What this tells us is that information abundance — made possible by America’s technology sector — is not alone the key to an informed democracy. In fact, it could be our curse.

At Knight, we’re exploring several responses to this new world:

- The Knight Commission on Trust, Media and Democracy, part of our larger Trust, Media and Democracy Initiative, is seeking to better understand how the new information environment has contributed to a significant erosion of trust in news and journalism institutions. It’s also going to explore the kinds of values that should guide the “new” distributors of news and fact. Commissioners include representatives from Google and Facebook, as well as experts in journalism, telecommunications and technology. Here’s where you can engage with their work.

- Along with a range of other foundations, Knight is helping to fund a first-of-its-kind effort to open Facebook data up to independent, scholarly research. Led by a distinguished group of scholars and the Social Science Research Council, the project will look at Facebook’s potential impact on elections in the U.S. and abroad.

- Knight is one of the early funders of the Center for Humane Technology — a nascent effort led by former Google leader Tristan Harris focused on understanding how ubiquitous digital technology can harm our well-being, and the ways in which we can design technology to improve our lives.

- We’ve also been commissioning research to better understand this moment. This includes major, national polls on how Americans view the relationship between the news media and our democracy today, their concerns about the spread of misinformation, perceptions of bias and accuracy in the news media, and experiments on possible solutions.

- We have also worked with a range of thinkers to produce a series of essays on various dimensions of what has been taking hold in our democracy.

We at Knight believe that democracy requires informed and engaged communities. Our response to the digitization of our lives and our communities is not to shirk that responsibility, but to ask head on how democracy can and will thrive in a digital age.

It’s a responsibility we all share — especially the corporations that are, in large part, shaping this new moment. It’s time for them to step up and to be a part of the effort to shape the rules, the values, and the norms that will enable democratic society to persist and to prosper into the new century.

As Zuckerberg said in his interview with Swisher, “I think we have a responsibility to build the things that give people a voice and help people connect and help people build community… I think we also have a responsibility to recognize that the tools won’t always be used for good things and we need to be there and be ready to mitigate all the negative uses.”

We agree. That’s why we, and others, stand ready to work alongside those who take seriously the new opportunities — and challenges — for our democracy.

Sam Gill is VP/Communities and Impact and Senior Adviser to the President at Knight Foundation. You can follow him on Twitter @thesamgill.

-

Arts / Article

-

Information and Society / Article

-

-

Information and Society / Report

-

Information and Society / Report

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·