Reconnecting communities: Restoring connectivity, economy and vibrancy

Cities across the United States are transforming urban landscapes once divided by highways, fostering new connections to rebuild communities. In the mid-20th century, highways were built that sliced through vibrant neighborhoods, causing displacement, disconnection and loss. However, recent years have seen a shift toward reimagining and reconnecting these spaces. Local leaders are spearheading projects to revitalize public areas and transportation infrastructure near highways.

In the mid-20th century, the building of highways and freeways in many Knight Foundation communities (and across the country) came at a cost––their construction divided and cut off vibrant urban neighborhoods. Communities lost housing, green spaces, businesses and places of worship. Families moved away and these neighborhoods faced a lack of public and private investment for decades. Yet, in more recent years, we have seen local leaders building plans to reimagine, reconnect and revitalize the public spaces and transportation infrastructure adjacent to these highways and freeways in Knight communities.

The construction of interstates, highways, and freeways in the mid-20th century had profound impacts on commerce. The social impacts were just as profound, but have been less widely recognized. | Graphic adapted from public domain footage available in the Prelinger Archives.

As longtime investors in local revitalization and inclusive public spaces, Knight has funded projects like 500 Plates in Akron, Ohio, to bring together residents to reimagine the decommissioned Innerbelt, and the establishment of community organizations like Reconnect Rondo in St. Paul, Minnesota, to develop plans to build a land bridge over Interstate 94. In 2022, federal funds were made available thanks to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which has created new opportunities to restore community connectivity, economy and vibrancy.

Knight Foundation supported Knight cities’ applications for funds and seven communities were awarded. In the first round, they received nearly $40 million to support planning and construction, representing 21% of the program’s awarded dollars. In 2023, an additional six Knight communities were awarded nearly $225 million. In October 2022, Knight also funded the Infrastructure Innovations Summit at Harvard Kennedy School to convene community leaders alongside infrastructure experts and others to discuss best practices in planning and implementing infrastructure projects.

Akron, Ohio

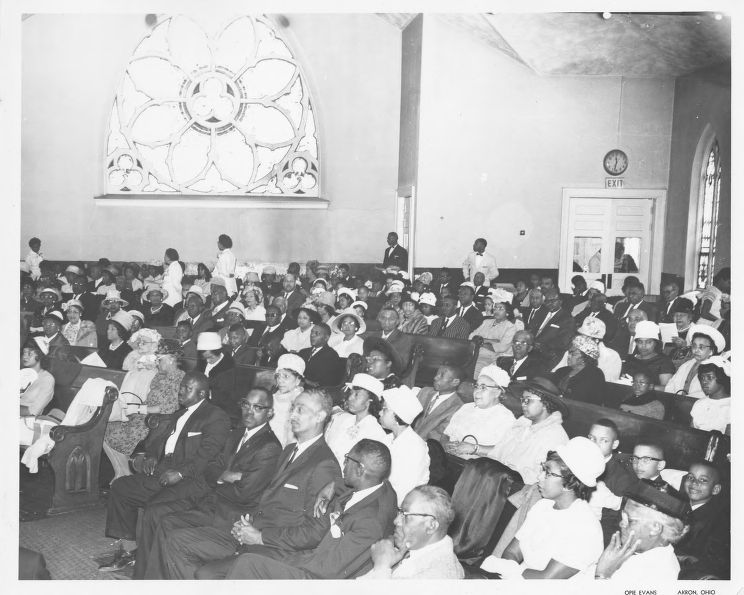

The Second Baptist Church was one of several African American institutions that were bought and removed to construct the city’s Innerbelt. | Photo by Opie Evans, provided courtesy of the University of Akron’s Archives and Special Collections’ Opie Evans Papers.

Akron, Ohio, was once home to a vibrant Black neighborhood west of downtown filled with hair salons, dry cleaners, cafes and churches. The residents knew one another and children played on the sidewalks. But in the 1960s, plans to build the Innerbelt Freeway through the neighborhood led to its decline. Construction started in 1970, cutting through the center of Black commerce on Wooster Avenue and shuttering over 100 businesses. The community never recovered, and the freeway still divides Akron today.

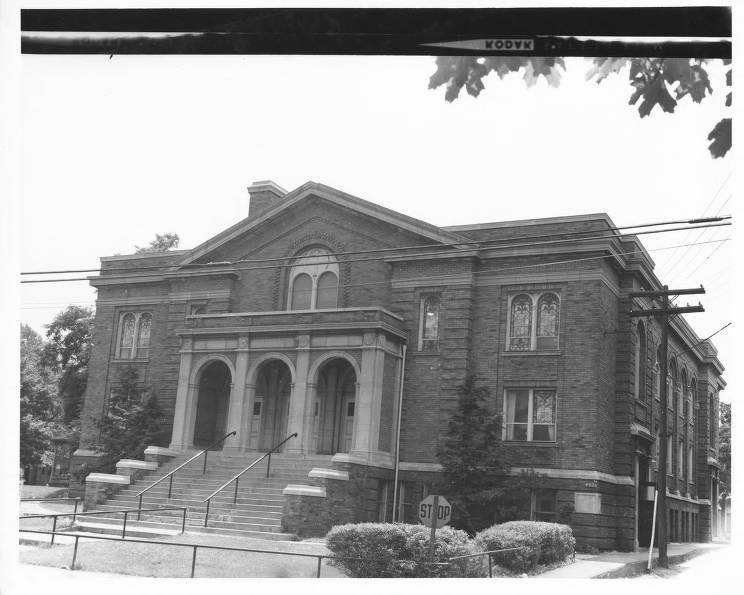

The Wooster Avenue Christian Church was among several predominantly African American institutions removed to build Akron’s Innerbelt. | Photo by Opie Evans, provided courtesy of the University of Akron’s Archives and Special Collections’ Opie Evans Papers.

In 2018, the State of Ohio decommissioned a one-mile section of the Innerbelt. This sparked renewed interest in engaging residents in a vision for the area and now empty public space. With support from Knight Foundation, Liz Ogbu, urban planner and spatial justice expert, worked with the City of Akron and community stakeholders to conduct a series of resident engagement events in 2022.

The first event, the Akron Innerbelt Reunion, was held at the Akron Urban League and invited families that have been displaced or harmed by the Innerbelt’s construction to come together. The second was an open streets event where people could walk or bike on the decommissioned freeway and share their ideas for what the land should become. Finally, the Rubber City Jazz and Blues Festival used the space as a venue for musicians to perform. These in-person engagement efforts complemented a series of online surveys and powerful recorded interviews with prominent Black leaders, now archived as the Innerbelt History Collection.

WSJ Photo Essay: An Akron Highway Cut Off a Black Community. The City is Trying to Fix It. WSJ: Black Community Cut Off by Akron’s ‘Road to Nowhere’ Seeks to Undo Damage

Akron’s future vision for the neighborhood where the Innerbelt now stands puts residents, families and their stories at the center. In 2023, Akron received a $960,000 federal Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program Planning Grant to support the future of this work––the only city in Ohio awarded such a grant. This grant is matched with $200,000 in support from local Akron funders. Today, the City of Akron is conducting an RFP process to select a consultant to lead future planning that engages residents.

Charlotte, North Carolina

The Historic West End in Charlotte, North Carolina, is a vibrant cultural hub located just a mile outside Uptown. Home to Charlotte’s only historically Black university, Johnson C. Smith University (JCSU), and several historic neighborhoods, the area’s homes and churches date back to the first half of the 20th century and represent the rich history of the Black community. For generations, residents built strong ties to their community and to one another in the district, raising families, starting businesses and caring for their neighbors during and after segregation. The Historic West End and Johnson C. Smith University have also served as incubators for Charlotte’s civil rights movement and Black leadership.

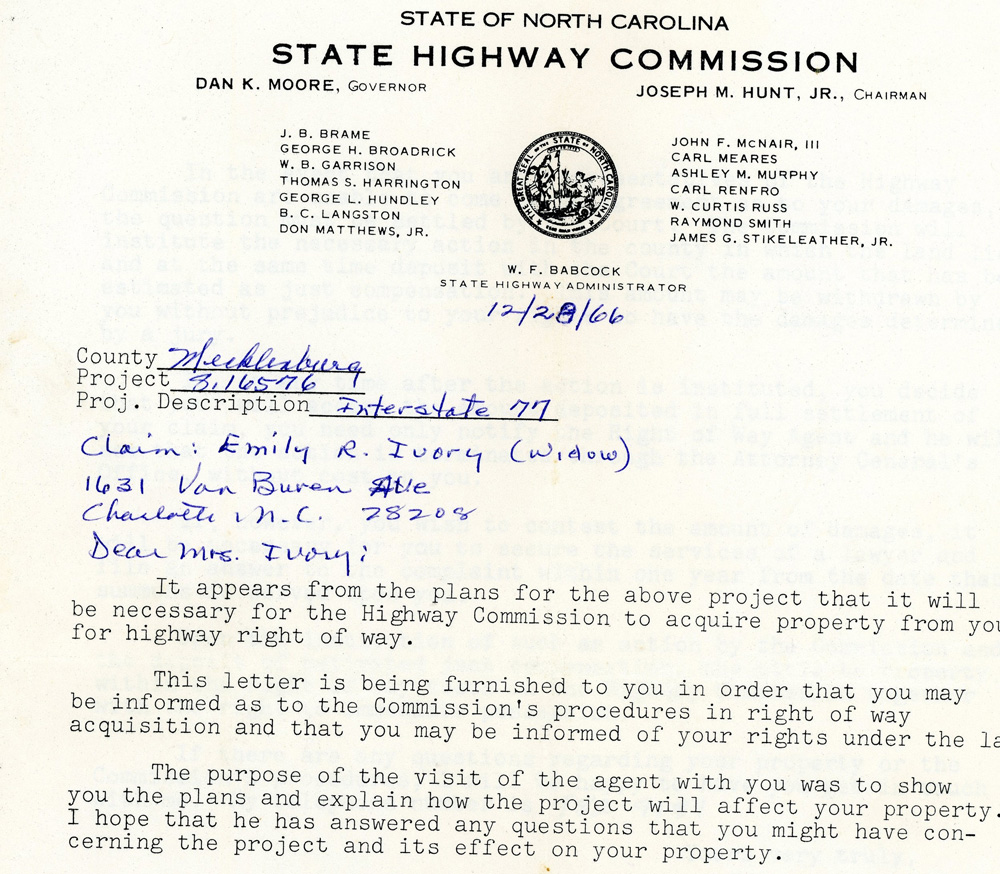

However, through the city’s Thoroughfare Plan in the late 1950s, the construction of three highways led to the displacement of over 240 families; destroyed once-vibrant neighborhoods; claimed public spaces, local schools and businesses; and divided wealthier white neighborhoods from poorer areas in the West and North sides of Charlotte. Redlining, white flight and the highways led to further economic decline and increased crime in the district for over 30 years.

The North Carolina State Highway Commission sent Emily Ivory – a single mother of three children – a letter on December 28, 1966 notifying her that the government would be seizing her property with compensation. | Photo courtesy of Darnell Ivory, Emily’s daughter. See the full letter on the James B. Duke Memorial Library’s Historic West End website.

Despite these challenges, recent private development and public infrastructure investments have spurred growth in the area, with the Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program presenting an exciting new opportunity and funding to support equitable and inclusive development in the Historic West End. Knight Foundation has supported engagement and planning in the West End since 2015, funding projects and ideas rooted in the ideas of local residents and business owners. This includes a resident-led planning effort called the 5 Points Forward Plan, which served as the basis of the City Department of Transportation’s Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program Planning Grant.

The 5 Points Forward Plan envisions mixed-use developments that provide healthy food options, safe pedestrian-friendly experiences, permanent representation of the culture and heritage of the district and affordable options in housing and amenities that include and benefit all residents. By prioritizing resident engagement and supporting equitable development, Charlotte honors the history of the Historic West End and builds a better future for all who call the district home.

Duluth

Duluth once thrived as an industrial hub, fueled by iron, but the steel crisis and the closure of major plants sent shockwaves through the city, leaving behind shuttered factories and widespread unemployment and poverty.

Amid this economic turmoil, plans emerged to extend I-35 through Duluth, promising newfound access to the city. However, the original proposal threatened to sever Duluth’s vital connection to Lake Superior, prompting local outcry. Thanks to community advocates, the plan underwent revisions, sparing key landmarks and preserving access to the waterfront.

As such, Duluth turned its gaze toward tourism, which offered a new purpose to its downtown district. Streets were revitalized, old warehouses were repurposed into vibrant cafes and shops, and the scenic Lakewalk emerged as an attraction.

In Lincoln Park, a once-neglected neighborhood, a group of visionary entrepreneurs saw potential where others saw decay. Through their collective efforts, the area experienced a renaissance, with new businesses sprouting up and hope returning to the community.

But perhaps the most exciting chapter in Duluth’s story of renewal along its waterfront is just now unfolding. Led by the Duluth Waterfront Collective, ambitious plans are underway to reclaim the I-35 corridor and reimagine it as a vibrant gateway to the city. These efforts––fortified by a Knight-funded study by the University of Minnesota Duluth––have garnered support from the city council, signaling a bright future for Duluth’s waterfront and its residents.

As Duluth continues to evolve, it serves as a testament to the power of community-driven change. Most recently, the receipt of $1.8 million from the new federal program ensures that in this era of transformation, the city has the necessary resources to implement vital initiatives. Though the challenges may be great, the spirit of innovation and determination that defines this city will undoubtedly carry it forward into a new era of prosperity and possibility.

Macon

Pleasant Hill stands as a testament to the resilience and vibrant culture of Macon’s Black community. Emerging in the post–Civil War era, this neighborhood blossomed into a hub of middle-class African American life, nurturing generations of scholars, artists and leaders despite the challenges of the Jim Crow South.

From its inception in 1879, Pleasant Hill thrived as a beacon of Black excellence, producing trailblazers like Georgia’s first Black congressman, Jefferson Franklin Long, and the legendary pioneer of rock and roll, Little Richard. The neighborhood’s schools and educators played a pivotal role in fostering community cohesion and prosperity, laying the groundwork for a flourishing enclave of residences, churches, schools and cultural centers.

At its heart, Pleasant Hill was once a center of community life, encompassing corner stores and the iconic St. Peter Claver Church and School, with its late Victorian brick façade. However, the construction of I-75 in later years brought about significant upheaval, displacing hundreds of homes and businesses and ushering in an era of blight and disinvestment. Despite these challenges, the spirit of Pleasant Hill endures, fueled by a deep sense of heritage and a commitment to revitalization.

Macon Bibb County recently earmarked $1.5 million to acquire a vacant school on Walnut Street, designated for conversion into affordable housing. Additionally, Knight Foundation, a partner, has contributed over $1 million to activate the Pleasant Hill Pathway of the Ocmulgee Heritage Trail. With an extra $500,000 grant from newly available federal funds, these combined efforts seek to reinvigorate Pleasant Hill and its surrounding areas.

After 60 years of challenges, Macon is embarking on a new chapter. Inspired by the past and fueled by the promise of renewal, the Black community of Macon stands ready to shape a dynamic future of its own making.

Miami

Overtown, a storied Black community in the heart of Miami, stands as a testament to resilience and community spirit. However, the neighborhood’s prosperity was marred by the far-reaching impact of the expansion of Interstate 95 in the 1950s and 1960s, a development that not only severed its physical landscape but uprooted the lives of thousands of residents.

In the shadow of this interstate behemoth lies a transformative vision known as the Underdeck–now called the Rev. Edward T. Graham Greenway–slated to take shape beneath I-395. This ambitious project holds the promise of reconnecting Overtown to its neighboring communities and reimagining the role of the interstate from a divisive barrier to a unifying force binding together disparate neighborhoods.

Stretching across 33 sprawling acres and nearly a mile in length, the Underdeck is poised to become one of Miami’s largest public spaces. Its strategic location will bridge the gap between burgeoning urban districts, including Historic Overtown, Downtown Miami, the Arts and Entertainment District, Wynwood, and Edgewater/Midtown, fostering a sense of cohesion and interconnectedness.

More than just a park, the Underdeck is a multifaceted vision for strengthening community and civic engagement. It will serve as a vibrant hub for recreation, offering inclusive spaces for play and exercise that cater to individuals of all abilities. Moreover, its innovative design will address pressing environmental concerns, serving as a green infrastructure solution to manage stormwater runoff and mitigate the effects of climate change.

Following Knight Foundation’s initial investment of $475,000 to engage local advocates to shape the future of the Underdeck, this collaborative effort received a significant boost with a $60 million federal funding allocation, underscoring the project’s significance on a national scale.

As the Underdeck takes shape, it stands as a testament to Miami’s commitment to equity, sustainability and community-driven development. With each shovel of earth and stroke of design, Overtown’s spirit of resilience finds expression, inspiring hope for a brighter, more interconnected future for all who call Miami home.

Philadelphia

Philadelphia’s Chinatown has been a thriving family-oriented community since 1871. However, in 1966, the state and local government announced their plan for the Vine Street Expressway. This plan involved the demolition of the community’s Holy Redeemer Chinese Catholic Church and School, which sparked outrage and opposition among residents, business owners and church leaders.

The Holy Redeemer Chinese Catholic Church and School, seen here in an image from circa 1933, was slated for demolition to build the Vine Street Expressway, but was spared. The community around it, however, was severely disrupted by the roadway that divided the community’s main commercial corridor and residential district with unsafe walking conditions to this day. | Photo from the Historic American Buildings Survey via the Library of Congress.

Despite the community’s opposition, the six-lane below-grade interstate was completed in 1991, cutting across the central part of Philadelphia and creating a physical barrier. Its construction destroyed homes, businesses, sidewalks and amenities such as the local community garden. Although the community was able to save the Holy Redeemer Chinese Catholic Church and School, the expressway still divides the area from the main commercial corridor and neighborhood, with unsafe walking conditions.

While Vine Street Expressway continues to negatively impact Chinatown, the community has been working tirelessly to reconnect with its northern counterpart. In the last three decades, the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation (PCDC) has commissioned, planned and implemented projects to repair the damage done by the expressway.

Members of the community lobbied and protested to save The Holy Redeemer Catholic Church and were ultimately successful. A smaller version of the expressway was constructed sparing the church. | Photo courtesy of The Robert and Teresa Harvey Photograph Collection via the Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia.

In 2008, PCDC implemented the 10th Street Commercial Corridor Revitalization project, and in 2010, they renovated the pedestrian bridge over the expressway to create the 10th Street Plaza. This small plaza has become a go-to place for PCDC’s public programming and community events including a vigil for anti-Asian hate victims and play space for hundreds of neighborhood children. PCDC played an active role in hosting the 2016 Every Place Counts Design Challenge led by the U.S. Department of Transportation, which provided a valuable opportunity for the Chinatown community to reimagine the expressway.

Furthermore, community-driven studies such as PCDC’s 2017 Chinatown Neighborhood Plan and the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission’s (DVRPC) Reviving Vine report helped to inform the plans. The capping strategy, which has three proposed concepts covering two to three blocks based on community input to restore connectivity, is further supported by Phila2035, the City’s Comprehensive Plan. Finally, Knight supported PCDC’s equity lab, which built up community capacity and language of residents to talk about planning and build an understanding of what it means to achieve equity.

The decades of engagement ultimately laid the groundwork for the $1.8 million Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program funding, in addition to $2.2 million matched from local funders, which builds on these ideas and recommends developing strategies for a cap or partial cap. Although the Vine Street Expressway has caused long-term harm to Chinatown, the community’s advocacy and resiliency positions the neighborhood to capitalize on Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding to transform the public realm and ultimately reconnect Philadelphia’s historic Chinatown.

St. Paul

The story of the Rondo neighborhood in St. Paul, Minnesota, is one that is all too familiar. A thriving Black community, Rondo was once a close-knit neighborhood with a vibrant social, cultural, economic, civic and spiritual fabric, filled with families who knew and supported one another. However, in the 1950s, plans for the construction of Interstate 94 were implemented as an urban renewal project, and the proposed route ran right through the heart of Rondo’s business district and neighborhood.

I-94 was constructed, in part, at the former intersection of Rondo and Fairview Avenues, as seen in this photo from September 1967. | Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society, used with permission.

Despite significant opposition from residents and community leaders who feared displacement and destruction of their homes and businesses, the freeway was built, and the neighborhood was divided. Due to redlining and discriminatory banking practices, there were virtually no options for relocation within the neighborhood for most residents. Therefore, many were forced to move out of the neighborhood and community.

However, in recent years, there has been a renewed effort to further engage the community and address the lasting impact of interstate construction. The community has come together formally through the establishment of a nonprofit organization, ReConnect Rondo, focused on reviving the once economically vibrant community and creating Minnesota’s first African American cultural enterprise district connected by a community land bridge. This effort is intended to establish a collective plan working hand in hand with the community to revitalize the neighborhood, including initiatives to support small businesses, improve transportation and create affordable housing.

Thanks to Knight Foundation’s funding, the community has been engaged in developing a vision that includes the creation of the Rondo Commemorative Plaza and establishing a land bridge to reconnect the divided neighborhood and to establish an African American cultural enterprise district. But there is still much work to be done to fully address the negative repercussions of the interstate and support the revitalization of this important community.

The recent $2 million in federal planning grants toward funding ReConnect Rondo’s vision of restorative development will help accelerate efforts to bring this vision to fruition. An additional $500,000 will be matched by local funders.

Rebuilding and reconnecting a community and healing from the wounds of the past is a long process. It requires a commitment to listening to elders, descendants, existing residents, community members, organizing community members and organizations and leaders to envision a brighter future for Rondo and St. Paul.

Long Beach, California

Shoreline Drive was once a part of California’s interstate freeway network as Interstate-710, built as an “urban renewal” project after World War II. Unfortunately, this project had devastating consequences for the working-class Magnolia and West Beach neighborhoods. Homes and businesses were demolished to make way for the divided road that operates at highway speeds. The result was the separation of residents from the waterfront and green space.

The current landscape of West Shoreline Drive is a park sandwiched between the northbound and southbound lanes. The park, Cesar Chavez Park, is a great asset to the neighborhood. However, its proximity to a fast-paced roadway and the on and off ramps of Shoemaker Bridge makes it dangerous for pedestrians, while creating poor air quality. This transformative project will convert the urban freeway into a landscaped, lower-speed roadway.

Cesar Chavez Park is separated from the nearby community by roadways. West Shoreline Drive runs through it, creating dangerous pedestrian conditions. | Imagery copyright Google Earth, with data from CSUMB SFML, CA OPC, LDEO-Columbia, NSF, NOAA, SIO, NOAA, US Navy, NGA, GEBCO.

The West Shoreline Drive project is expected to combine the southbound and northbound traffic lanes, opening up 5.5 acres of park space and expanding Cesar Chavez Park. This will serve as a gateway to better connect residents, visitors and workers to the Pacific Ocean, local destinations and downtown Long Beach. The project received a capital construction grant of $30 million in federal funding through the Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program.

The project evolved as part of Long Beach’s application for Knight Foundation’s Reimagine the Civic Commons. This initiative aims to revitalize public spaces in cities across the United States, creating more vibrant and equitable communities. Knight Foundation has been an early partner in this work, committing $50,000 in funding toward programming in Cesar Chavez Park to engage residents in the neighborhood and downtown in arts and connectivity that are authentic to the diverse communities.

The West Shoreline Drive project is an excellent example of how cities can reimagine their public spaces and transportation infrastructure to better serve the needs of their communities. By creating more pedestrian-friendly, accessible spaces, we can build stronger connections between residents, visitors and workers. This is an essential step toward creating a more connected, equitable and engaged Long Beach.

Wichita, Kansas

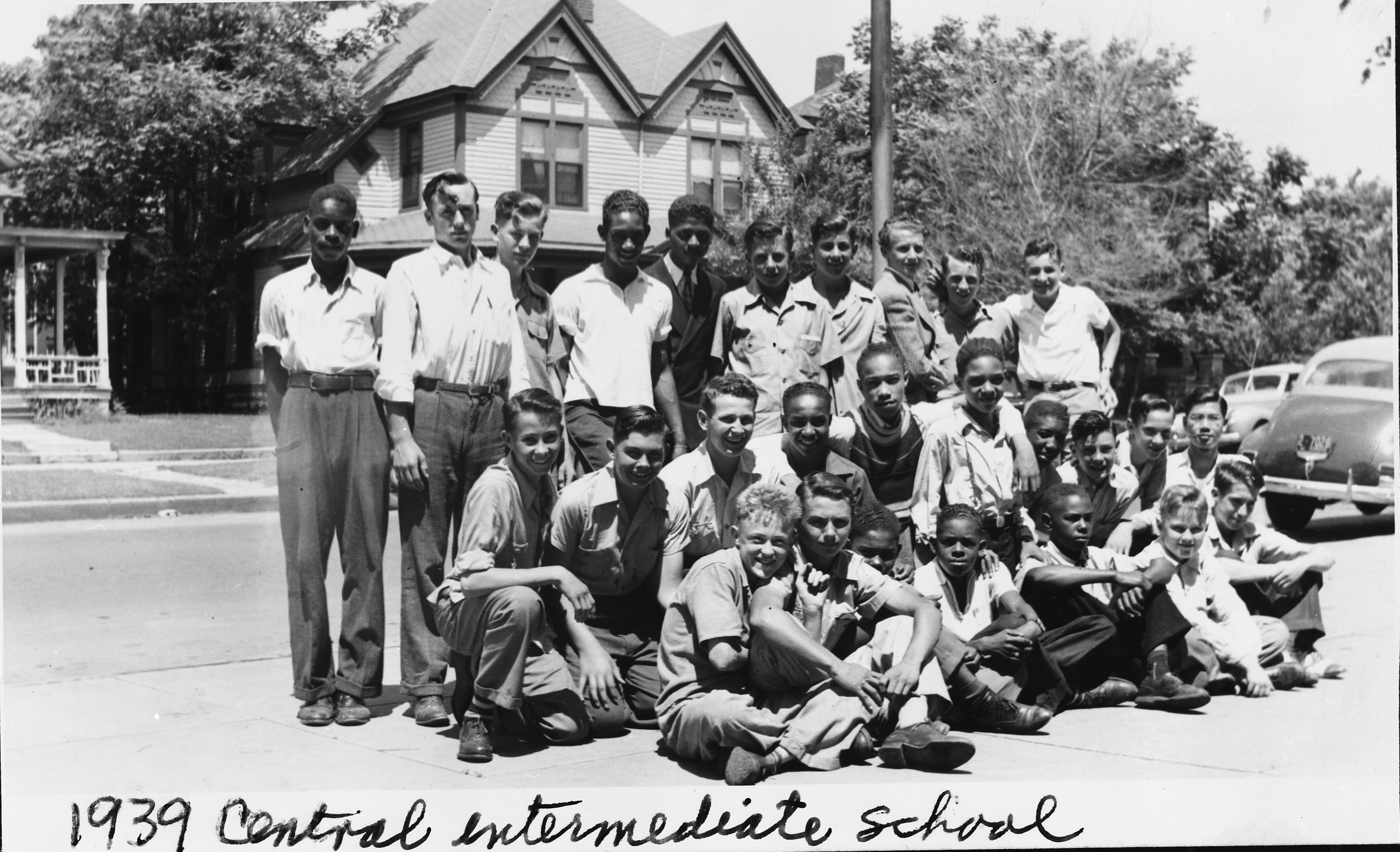

In the 1920s, Wichita’s North End neighborhood, located north of 21st Street, was a thriving hub of local businesses and a vibrant community. At that time, it boasted a growing Latino population, with the population increasing from 135 people in 1915 to 934 in 1925. The neighborhood’s vibrancy and connection suffered when multiple railroad lines were constructed that cut through 21st Street. These tracks brought about two significant challenges that led to the decline of this once-thriving community. The Latino population had soared to nearly 50,000 community members of Mexican heritage.

In Wichita – unlike other cities – Latino children were not restricted to segregated schools, but did face pressure to fit in by not speaking Spanish, according to the University of Wichita. | Image courtesy of Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum via ‘Somos de Wichita’ at the University of Wichita.

First, the railway lines created a disconnect between two historically and culturally rich neighborhoods—the North End and North Wichita, which is situated east of the North End and is home to some of Wichita’s predominantly Black communities. This separation had a profound impact on the sense of unity and cohesion between these neighborhoods.

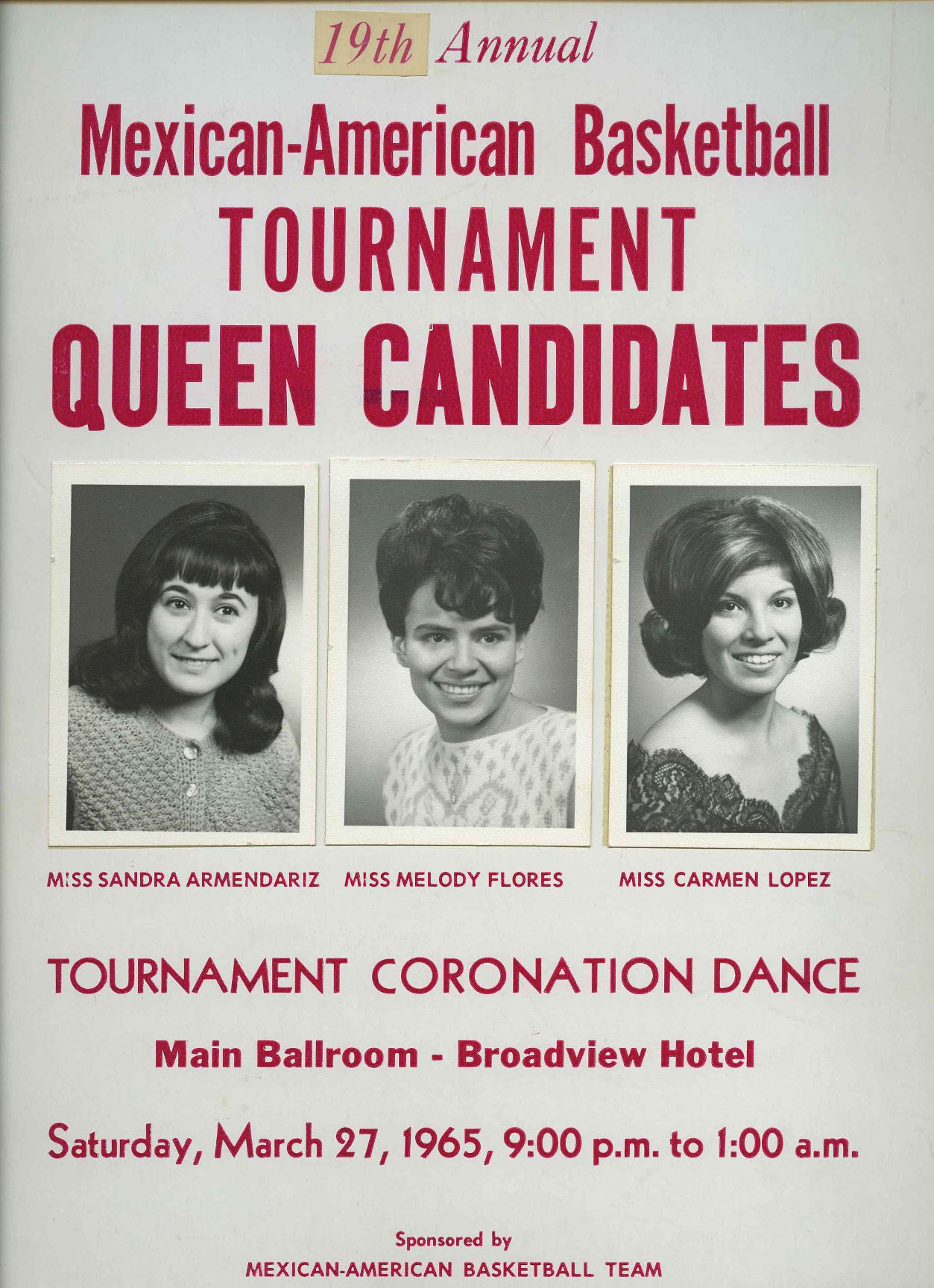

Mexican American youth in Wichita participated in traditions like beauty pageants, feeling that their Hispanic cultural traditions were, “embarrassing holdovers from their parents and grandparents,” according to the University of Wichita. | Image courtesy of Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum via ‘Somos de Wichita’ at the University of Wichita.

Additionally, the tracks saw approximately 75 train movements per day, often traveling at low speeds and crossing 21st Street in unpredictable intervals. As a result, motorists, pedestrians and bikers were forced to endure waiting times ranging from 5 to 90 minutes. This inconvenience discouraged many Wichitans and businesses from venturing into the area surrounding 21st Street, leading to a decline in economic development.

Recognizing community-led efforts to reconnect the North End, Knight Foundation awarded a $150,000 grant to Empower Evergreen (EE) in 2021. EE is an organization dedicated to serving the North End of Wichita, focusing on connecting the Hispanic community to educational, workforce readiness and small business development opportunities. This grant was intended to foster community engagement, identify strategies to enhance community impact, inform redevelopment plans and establish a neighborhood catalyst strategy, a participatory process that engaged residents and other key stakeholders to activate and pilot ideas in the North End. This effort garnered support from the the City of Wichita and propelled the initiative forward as a Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program application. In 2023, they were awarded a $1 million Planning Grant, which will allow for a comprehensive plan to reintroduce connectivity to the North End via the east-west transit line, the construction of sidewalks and bike and pedestrian pathways, and the development of solutions catering to the needs of individuals with disabilities.

Conclusion

The steps each of these communities have taken – while significant and ambitious – are just the beginning. Reconnecting communities will cost millions of dollars and many years of work. Engagement of community cannot be static and will need to be embedded throughout the lifecycle of these projects to maximize impact.

Ultimately, it is critical that cities and developers build with community not just for community.

Rebecca Dinar and Paul Blake in Miami contributed to this story.

Recent Content

-

Community Impactarticle ·

-

Community Impactarticle ·

-

Community Impactarticle ·