COVID-19 has shown we all need public space more than ever

Successful cities will find new ways to design spaces everyone can access, Knight Public Spaces Fellows say

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended basic assumptions that have long anchored just about every facet of society, from home and family to work and politics. It’s also brought into question the balance between private and public space, and the very definition of just what “public” is.

Last year, Knight Foundation inaugurated the Knight Foundation Public Spaces Fellowship. The seven fellows come from diverse backgrounds and have different professional engagements with public space, but each has in common a longstanding professional commitment to the creation and improvement of public space.

As COVID-19 tears through communities across the U.S. and around the world, it has highlighted the critical role of public space as an essential parameter of public health, and it has brought into sharp relief the systemic inequity of access to public space. In their own ways, each of the seven fellows has been tackling this inequity, calling for and making public space accessible in fairer ways.

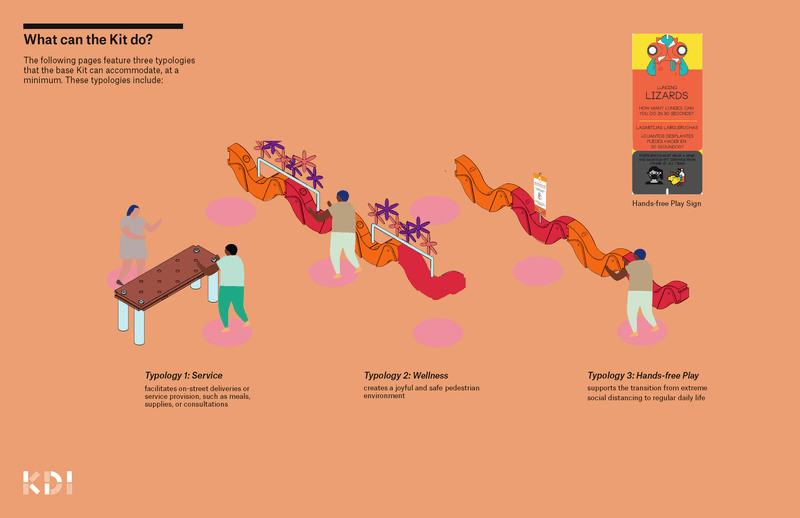

“We know public space is an essential part of mental health, public health and economic stability, so this one thing — public space — would make the disparities of equity during this pandemic less stark,” says Chelina Odbert, executive director of Kounkuey Design Initiative (KDI). “This is not the time for a 10- or 20-year plan,” she adds. “We need to treat this with urgency.”

To make new parks, cities spend years, sometimes decades, building consensus, allocating budgets, procuring teams, making designs, and administering construction. Now, faced with an immediate public health need and urgent demand for outdoor space that allows for safe physical distancing, that project delivery pipeline has become unacceptably slow.

“If public spaces go through the traditional track, they won’t rise to this occasion,” warns Odbert. “We need new financing strategies, new physical forms of public space, new design and decision-making processes, which will take political will, strong leadership, optimism and a belief in the possible instead of a commitment to the status quo.”

As the commissioner of Philadelphia Parks & Recreation, Kathryn Ott Lovell is doing just that. Invoking the department’s history as part of the city’s Department of Welfare, she has retooled her approach to deliver immediate relief with recreation and public space. “For 57 years,” she explains, “the department has had a Playstreets program, closing off streets and delivering meals to community members.” Along with the meals comes a duffel bag filled with recreational items — hula hoops, bubbles and jump ropes. “When we were thinking about how best to address the COVID-19 crisis, we thought, ‘let’s put all our eggs in the Playstreets basket this summer.’”

Because of the neighborhood-based nature of the program, the approach limits transportation between home and park, and it keeps density low, making it an ideal shared experience in a time of physical distancing. Design consultants, including KDI, have contributed modular and adaptable play equipment. “If kids can’t come to us,” Ott Lovell says, “then it’s our moral responsibility to get to the kids.”

Oakland-based landscape architect Walter Hood shares this sense of urgency and willingness to innovate. Recognizing that arts- and performance-based groups face immense challenges as a result of the pandemic, he reached out to the City of Oakland on behalf of a local nonprofit dance organization. He proposed converting a neighborhood street into one of Oakland’s Slow Streets, transforming it into a venue for dance rehearsal and performance, and, in so doing, creating a novel type of public space.

In his personal life, as a resident of Oakland, he also took it upon himself to plant a series of trees on the sidewalk alongside his studio. This action had the effect of creating a sense of space. “People stop along the sidewalk now,” he says, referring to the sense of place and shade the trees now provide. An example of what he has defined as “hybrid landscapes,” the plantings are neither public (as a matter of contract and project delivery) nor entirely private (in the sense of being restricted to him). Instead, they provide shaded area to be shared by his community.

One of the consistent themes that has emerged about public space in the context of COVID-19 is a sense that public space need not be permanently fixed to a particular locality. Rather than something drawn in ink onto a static city map, it can move and evolve over time, like Philadelphia’s Playstreets or Oakland’s Slow Streets. This is an approach to public space-making also taken by Erin Salazar, the executive director of Local Color, an arts organization in San Jose, California. The group, which commissions artists to produce work in the public domain, is launching a new program that will provide funding for local artists to paint local storefront windows. This will not only provide artists with much-needed work, but it will also create an outdoor self-guided arts walk, drawing residents to local business and into a shared experience on the sidewalks.

“This pandemic has made everyone afraid of so many things, and, unfortunately, a fear of each other is one of those things,” says Salazar. “This project will bring the community outdoors, and people will be able to see human beings making art and appreciating art.”

More than the designation of a place as public, this sense of shared experience — of people in a place together — has come to so clearly define “public space” through this pandemic. Take New York City’s High Line, for example. Because it is technically coded as a building, and because its narrow dimensions made physical distancing effectively impossible, it was forced to temporarily close during the height of the pandemic. Robert Hammond, the High Line’s executive director, was able to stroll part of the landscape during the closure. “Without people,” he says, “it felt so melancholy. It was missing the key ingredient.” Now, as the High Line reopens for timed and ticketed visits, it has begun to reestablish the essential element — people sharing public space — that has made it such a landmark.

This simple act of seeing other people, of sharing space with others, is a fundamental part of the human experience. By limiting that physical connectedness, COVID-19 has reinforced — loudly so — the importance of that social experience. For Anuj Gupta, the former general manager of Reading Terminal Market, a public market in Philadelphia, public space will be a much-needed and necessary tonic to months of physical distancing. “This pandemic has been a trauma to the community at large, and public space is a way to heal it,” he says. “Human beings are inherently social, and we are retreating further and further into our silos,” he cautions, citing the move toward digital communication that the pandemic has accelerated. “Public spaces are one of the few spaces that still offer the opportunity to engage in social behavior.”

For those who have ready access to it, public space, like other forms of infrastructure and public services, can seem something of a given. The pandemic, though, has brought newfound scrutiny to public space, highlighting its value in public health and laying bare inequities of access. “One thing about this moment is that we’re starting to see just how important it is to use and have public space,” says Eric Klinenberg, NYU’s Helen Gould Shepard Professor of Social Science and the author of Palaces for the People.

“I got really interested in how public spaces are morphing and transforming during this COVID crisis,” says Klinenberg. “A number of libraries, for example, have effectively unfolded, moving services outdoors, and moving librarians to other spaces, finding new ways for people to access the library even though the building itself was closed.”

As municipalities and communities set out to create and update public space to meet new demand and emerging public health parameters, Klinenberg urges a long-term view. “One of the challenges of the moment is trying to balance the short-term needs with long-term planning considerations,” he explains. “One concern I have is that cities and states will make exceedingly short-term decisions about building for distance because COVID is on our minds. By the time such projects are completed, we’ll have made our communities more isolating and atomizing,” warns Klinenberg.

As Ott Lovell considers how to deliver public space in Philadelphia, she, too, recognizes the relative time horizons. “We are dealing with a pandemic, and I’m hopeful that it’s a snapshot in time — that we are not going to have to fundamentally change how we design public space in the future.”

For her, as for all the fellows, public space is one of the last venues for diverse, spontaneous shared experience, which makes protecting it imperative to civic engagement and the democratic experience.

“Everything we interact with is about how we want to interact with it. We don’t have to go to a bar to date, we don’t have to go to a grocery store to buy food, and we are handed Facebook feeds and Netflix queues,” she says. “Public space gives us this unique opportunity to interact with people we didn’t pre-select or choose, so a time like this shows us how critical it is that public spaces are truly public.”

You can learn more about the Knight Public Spaces Fellows by watching these recent episodes of “Coast To Coast,” where Knight program director Lilly Weinberg interviewed several of the fellows:

- Episode 1: How Can We Rebuild Our Cities? with Eric Klinenberg

- Episode 3: Rebuilding With New Models for Public Space Engagement with Kathryn Ott Lovell and Robert Hammond

- Episode 4: Taking Back Our Streets During COVID-19 with Chelina Odbert

- Episode 10: Building Equitable Public Spaces with Walter Hood

John Gendall is a New York-based journalist and communications consultant.

Photo (top): Muralists in downtown San José, 2020. Photo by Local Colors.

Recent Content

-

Community Impactarticle ·

-

Community Impactarticle ·

-

Community Impactarticle ·